My original plan had me on the road to PAX unplugged already, but that’s going to be a bit delayed. No real post for the day, but a preview of something I’m working through whose final form I am not yet sure of.

Monthly Archives: November 2018

The Mail Must Get Through

Over on twitter, @ericvulgaris remarked that the next step in his D&D campaign was for the party to start delivering mail in Phlan, and I responded somewhat excitedly because this is a wonderful idea, and one that does not show up in nearly enough games. Consider: delivering mail requires:

Over on twitter, @ericvulgaris remarked that the next step in his D&D campaign was for the party to start delivering mail in Phlan, and I responded somewhat excitedly because this is a wonderful idea, and one that does not show up in nearly enough games. Consider: delivering mail requires:

- A lot of open space, but a predictable core of destinations to return to over time.

- A group that is capable of dealing with that hazards of travel, which are environmental but also may be more direct, like bandits or hazards.

- An employer and a paycheck.

To me, that absolutely sounds like a formula for adventure. You have a unifying element (the job) that is strict enough to justify unity but which still leaves a ton of leeway within it. You have a steady source of challenges and threats, as well as an easy tool to introduce new ones (simply adding a new destination to their route) plus the variability that comes from travel.

What’s more, once you open the door to the mail, you can start thinking about the things that are mail-adjacent. The history of the mail is fascinating, but for those of us with a D&D bent, knights of the post could have a host of opportunities. You can look to historical examples like traveling doctors or horseback librarians for inspiration, and you can extend them to the fantastical. Consider how much it might matter to a town when the only spellcasting cleric they have access to is the one who comes through once a month or so with the mail? And, of course, these rough and ready souls can also be expected to handle the occasional monster.

The adventuring benefits of this model are obvious, so why don’t we see more of it?

Well, first, to give it’s due, there are games that do this. This is the default structure for Mouseguard and Dogs in the Vineyard, and it was one of the default modes of play in Legend of the Five Rings (doing a procession through your lord’s holdings). But for all that, it’s an outlier – a dungeon map is a normal thing, but a delivery route map would still be an anomaly in most written adventures.

Given that, there are three real challenges to implementing this model.

The first is progression: as characters level up, how do you deal with that? Having the stops on their delivery route JUST HAPPEN to have greater challenges each time they come back feels pretty fake, so are they just going to outgrow this?

The second is that it calls for a wider range of challenges, and some of those challenges aren’t challenges at all. That is, the things the characters may be called on will not be limited to fighting. Some of the challenges will be based on skills, so the system needs to support that, but other challenges are more simple. Consider the Cleric sanctifying a well – there’s no roll of the dice or challenge in that, but it’s very important to the fiction. It can be MADE challenging or interesting, but that takes a lot more work than creating a monster encounter1.

The third is that we tend to design settings to be disposable. Tensions are set up during creation, resolved during play, and then we generally move on2. I think we like the idea that we might come back later and see how things have changed, but there is almost no support for how to run such a thing, so the result often falls flat.

Now, I’ll admit, these are non-trivial challenges. If I were starting a D&D campaign tomorrow, I’d need to have solutions to all three, and I don’t think those solutions exist yet. But I also think they’re all solvable problems.

I might do a part 2 with some examples of solutions, but in the short term, let me offer some tips for how I would mitigate these things:

- I would schedule out delivery in game in advance. Not in huge detail, but just enough to say that the next route will be A=>B=>C=A in about 1 month. It won’t matter a huge amount at first, but it will make life easier as we progress, because:

- I would treat a single cycle through the route as an important design unit. When a route it completed, that’s when we would do any downtime-equivalent, and where I would make changes to the route.

- That is also when I would hand out rewards, including XP. Leveling up happens BETWEEN route cycles, and the biggest XP driver is mission success, not monsters killed.

- I would start with a small route and add in stops, but try to keep it to 5-6 stops top. That number is from my gut, so it might change, but it feels like there are only so many places they can keep in mind.

- I would make other mail folk into named NPCs, partly to reinforce the larger setting, partly to create a pecking order because:

- I would make changes to the routes and make those meaningful. As characters level, adding a more dangerous stop to their route makes sense, but so does dropping a boring one. And, critically, that stop now goes to someone else. Maybe they’re the rookie crew (who might need some help from the old hands sometime) or maybe they’re that asshole’s crew who totally snaked the village with the hot springs because it’s such a great place to stop.

- I would enter with very flexible ideas about the group’s duties and try to tune those based on player choices and priorities. That said, if there are obvious gaps, I will happily have NPCs in other crews fill them and use that as a complicating factor.

- The Patron NPC will be distant, but the logistics NPC will be always at hand and constantly annoyed.

- I would re-read Going Postal before I start.

I think it would be pretty doable at the table, so now I find myself dwelling on how I’d make it a product. Thoughts, comments and suggestions welcome.

- Not that I’m suggesting that good monster encounter design doesn’t require skill, but the simple truth is – with D&D and it’s family especially – they’re just a LOT easier to create. This is especially true for a written product because fights are largely one-size-fits-all, whereas non-fights often rely on things like personalities of and relationships with NPCs, which are more emergent in play. ↩︎

- An exception to this can be found in city games, where there size of the city allows us to mask this pattern, and there are lessons on re-use to be taken from there, but that is also a fairly neglected model. ↩︎

Swap Space and You

I have another topic that is growing as I write it, but I wanted to dip into a sidebar that struck me while I worked. I am writing this on an iPad. That is not very important, nor is the fact that I am a big fan of the device, but it did get me thinking. If you’re unfamiliar, one of the things about current generation iPads is that they are way more powerful than they have any business being. Some of this is due to hardware advances, but a fair amount is because the iPhone/iPad is a newer platform than the PC, so certain things were baked in from the ground up.

I have another topic that is growing as I write it, but I wanted to dip into a sidebar that struck me while I worked. I am writing this on an iPad. That is not very important, nor is the fact that I am a big fan of the device, but it did get me thinking. If you’re unfamiliar, one of the things about current generation iPads is that they are way more powerful than they have any business being. Some of this is due to hardware advances, but a fair amount is because the iPhone/iPad is a newer platform than the PC, so certain things were baked in from the ground up.

Specifically, iOS software has been historically designed for a very resource constrained environment. This makes sense. Early phones were not very powerful, so you had to be very careful in what you let them do (especially if you’re Apple and very invested in customer experience). One specific area where this comes up is memory.

You’re probably familiar with the idea of RAM – the memory that your computer keeps the things it’s actively working on. This memory is faster than the memory you use for storage, and the more RAM you have, the more stuff your computer can do. Simple enough.

Now, the thing is your computer only has so much RAM (and it used to have much less!), so some long ago nerds came up with the idea of swap space. In short, when your RAM gets too full, your computer will try to find parts of it you’re not using at the moment and move those across to storage (like your disk) to free up space. When you need them again, it moves them back. You lose a little bit of performance (this moving takes time) but your computer is able to run things that it otherwise would not have enough RAM for. Yay!

The thing is, iOS doesn’t do this. Lots of reasons why, but the long and the short of it is that if something uses too much RAM, it gets dumped. The app crashes. End of story.

In practice, this is not too much of a problem. Originally, iOS couldn’t even multi-task, so there was very little competition for RAM. Even after multitasking was introduced, the system remains outright draconian about reclaiming resources. The result is that if you want your app to run well on iOS, you need to create a tighter package. The extra overhead on a computer allows for a certain amount to slop that iOS just won’t tolerate.

So what does that have to do with anything?

Well, it has a lot to do with you, and it has a lot to do with games (and with almost anything we want to share with people).

Most of us, most of the time, act like iOS. We have a certain amount of capacity, and if a message is communicated in a way that will fit within that capacity, then we can potentially absorb it. But if it exceeds that capacity, there’s a good chance we’ll “crash” – reclaim the resources, discard the message and move onto the next thing.

But – and this is the trick – that’s not always what we do.

Sometimes we’re perfectly willing to sit down and read 300 pages of content or watch 10 hours of videos or otherwise dramatically exceed our capacity in order to learn something. This leads to an apparent paradox where people want both more and less content.

This is where the metaphor kicks in – when we care, we create swap space.

Which matters because it’s the answer (or not-quite answer) to a common question in game design – what is the right size for my game. It would be awesome if there was one answer, but the real answer seems to be “the more people care, the bigger it can get”. This is borne out by numerous examples, but perhaps most tellingly by the very idea of the “supplement treadmill” – if people are bought into your game, they want more.

Which means the question to ask is not “how big?” but rather “how can I convince people to care if they don’t already?” Thankfully, the answer suggests itself in the problem – the case for why people should care is something you need to fit in their current capacity.

At this point, we get into familiar territory – elevator pitches, quickstarts, promo pages – there are a lot of ways to present the small part of your game that will excite people, and a lot of practices that surround them. But the important thing about designing this for other people’s capacity is that you are designing it for other people.

That maybe seems obvious, but consider. Often, when we craft a quickstart, a demo, a pitch or the like, our goal is to create something small that is true to the larger product. This is not a bad instinct – we want to be honest and give a clear reflection of the bigger product. But when we do this, we are designing to the product, not the people.

To be clear, this is not an invitation to lie or deceive. Rather, it is a rule of thumb to help prioritize which truths you want to bring to the fore. The simple reality is that any abbreviation is going to be incomplete, and you must make prioritization decisions. You absolutely can prioritize accuracy, but you will be better served prioritizing the things that make your game exciting, interesting or attention grabbing. Your summary – whatever its form – is an argument for your game, and it is allowed to be biased in favor of your game. It is, I’m afraid to tell you, marketing.

(And if you find yourself wanting to make a pitch for something that’s not in your game but you think is exciting and awesome? Well, maybe you need to think about putting it in your game. )

Navigating the Table

I love maps. Especially big outdoor maps. I don’t think that love is mandatory for this hobby, but I think it definitely helps.

The thing is, I have always struggled with how to convey the map into play at the table. A map is so open and flexible that it feels like narrowing it down to something I can convey at the table is an effort doomed to blandness.

The root of this is in my own mind. When players are in a place and want to go to another place, my process has always been “Imagine the line of their travel, Indiana Jones style, making note of each thing they pass through, and then provide some amount of travel activity for each thing.” This is very intuitive to me, because that’s how traveling in actual space works, and that’s what I want it to feel like, right? The problem is that it makes for fairly uninteresting descriptions at the table because they’re unfocused. They might offer a little bit of color, but there’s nothing to hook into the minds of the players to spark interest or action.

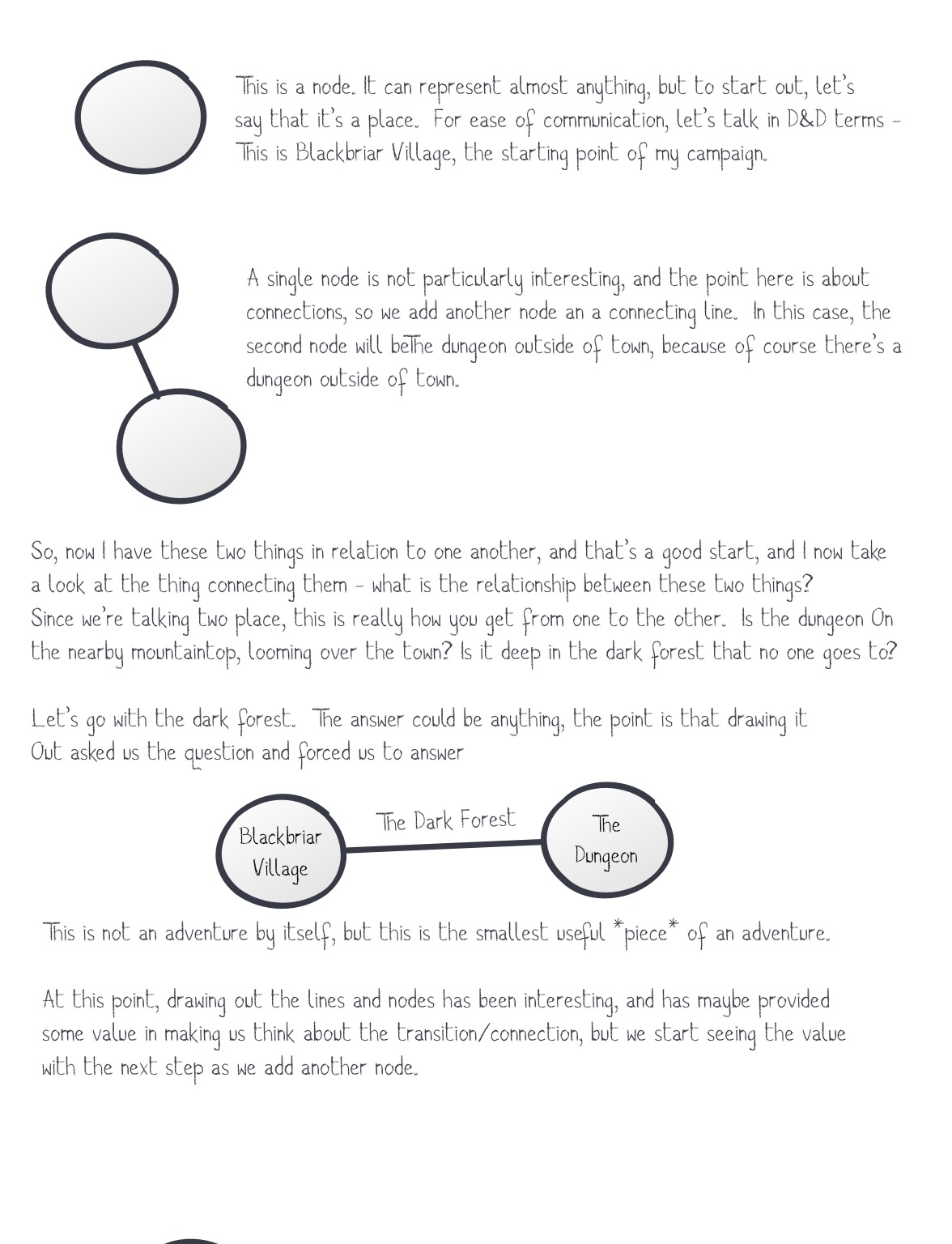

Video games solve this problem in a number of ways. A lot of RPGs just embrace the map and use line and node travel. That is, you hit a button to see a map that looks like this:

Then select a node that you want to travel to, and bam, you’re there. Nine times out of ten, the transition just happens, but if the game feels like it, it’s possible that an encounter or discovery happens during transition (which often adds a new node, temporarily or permanently, or otherwise alters the map).

This model works REALLY well, but I struggle with it a bit because I am expecting something more akin to an open-world game, like World of Warcraft, where I’m actually moving between space.

But I recently started paying attention to how these games handle their geography and realizing how much of it is sleight of hand. Most video game maps are functionally node based, and the “connective” elements are surprisingly small and thin. The geography introduces some constraints (adjacency) and opportunities (exploration) but practically it’s still a matter of moving from node to node.

All of which is to say, I think it may be time to make my peace with a line and node map at the tabletop, even if it’s just a functional overlay on a much prettier map.

Lessons From The Young

The roles seem well received so, at some point, I may need to write those up a little more. I suspect there’s also a player version to be had, but that seems like a daunting task, so we’ll see how that shakes up.

The roles seem well received so, at some point, I may need to write those up a little more. I suspect there’s also a player version to be had, but that seems like a daunting task, so we’ll see how that shakes up.

But I’m still chewing on the underlying Santorini issue, and have ended up looping back to it from a strange vector. My son is 9 years old, and we had the opportunity to play some RPGs this weekend. This is not new, but we got to do more than we usually do, and it was somewhat illuminating to me because on many levels he is looking at the same issues as our Santorini player – he is enthusiastic and engaged, but disinterested in work getting in the way of play.

The first two sessions we played were back to back 5e D&D and Fate Accelerated, with the additional twist that it was the same character between the two. Neither game was a perfect match, but the things that worked and didn’t were very interesting to me.

For starters, his primary motivation in making a character was to get a pseudo-dragon familiar, something he had discovered existed in an enthusiastic read-through of the Monster Manual. I 100% cannot fault this and wanted to support it, so we did charge and talked about what it would mean for various classes and races, and he ended up making a human bard (with a 20 Charisma and the Actor feat, no less). He loved some of the explicit bits – the skills he was exceptionally good at, the specific spells, stuff like that. He really enjoyed looking through the backgrounds and considering the RP hooks, but he also ended up reading ALL of them in order to find ones he liked. He groaned at some of the bookkeeping and largely wanted me to write stuff down. All in all, there were a LOT of choices to be made, and he cared a lot about maybe half of them.

Actual play was decent. I stuck primarily to things involving skill rolls because – as the one fight reminded me – a lone level 1 character can be killed by a stiff breeze. That actually made it a little hard to GM, because I had to be VERY CAREFUL about potential threats, but he had fun.

The next session started with just porting the character to FAE and starting up. He was not too excited by the character. It had taken a long-but-specific list of cool things he could do and replaced it with a shorter-but-broader list that pushed more of the creative work onto him. Now, the Little Dude has no shortage of creativity, but he definitely felt this was less exciting than having explicit cool abilities. I could theorize a lot about this – the balance of prompts vs. creation, the dangers of the blank page, constraints breeding creativity and so on – but in practice lists of cool things are pretty fun and they are more what he wanted. I “cheated” and gave him 3 stunts to start out to try to mitigate this, but the reality is that it would really need to be longer. Also, aspects didn’t really grab him – I think they felt more like constraints than opportunities to his eyes, but it may also have been that because I ported quickly, his aspect list was a little uninspiring.

The actual play part went great. He did lots of cool stuff, I had less need of kid gloves, and he absolutely got to be a hero working towards his big plot (defeating the evil priest that had killed his noble parents and seized their lands, a hook that had come out of the 5e prompts). But in the end, he had liked D&D better.

All of which suggests a sweet spot somewhere between these two. A little bit less bookkeeping than D&D, but a bit more explicit than FAE. Curiously, those are probably also very good Santorini style goals. The “Less Bookkeeping” part is pretty obvious, but the “more explicit” bit might need a little unpacking because it is easy to think of FAE as a “light” game, one that’s easy to pick up and play. That’s largely true in terms of pure page count, but it absolutely pushes the burden of creative labor onto the reader and player.

That is not a bad thing in general, but it’s a problem for an introduction. Worse, it’s also a blind spot for our community as we think about these things. When things don’t work because of the level of creative labor they demand, we have a habit of (overtly or passive-aggressively) blaming the reader of the game for not being creative enough. This is…well, it’s lazy bullshit. The idea that “creative players” (carefully distinguished from “normal players”, of course) will solve these problems at the table is a tool of shame that spares the designer from needing to actually think about the human beings using their game. This problem is independent of whether you feel authority likes with the rules or the GM – this is about the utility of the rules, and authority is just a smokescreen to hide that. While I may personally lean towards the GM as authority in my play, holy crap do I appreciate how much clarity a system-centric approach brings to writing because there is less of an easy cop out (though it can still find its way in).

Anyway.

The game he ran is nominally a Fate game, but in practice, the only overlap is the use of the dice. The rest of it is all born out of his head in an amalgam of terms and visuals he’s encountered in other places (our character sheets look a LOT like something from the World of Warcraft UI). He has a lot of classic GM foibles – his insertion NPC can be a bit scene-stealing, and he sometimes narrates our response to events – but they’re normal learning stuff. What intrigues me most is that at some point he very strongly picked up the idea of mixed results (“You succeed but…”) to the point where he uses them ALL THE TIME, so that part may take a little practice.

But it also revealed another tidbit to me in his relationship with the dice. When he rolls, he is really looking at the dice for what happens. He will occasionally remember that there are modifiers and such, but he does not have any instinctive sense of there being some invisible target number which is translated too and from somewhere off the table. This was weird to me at first (since target numbers, difficulties, move tables and such are all second nature to me by now) but if I remove my own baggage, it makes all the sense in the world. Why would he want interstitial steps?

So assuming I want to build to that, there are a few options, and the double-edged part of it is that they lean towards die pool systems. That’s double-edged because die pools are incredibly robust in a mechanical sense, but also can quickly become cumbersome game delays.

Option 1 is Blades in the Dark or a variant (possibly Blades of Fate). The number of dice equates to the chance of success, the highest single result tells you what kind of outcome (good, mixed, bad) you get. Building the pool is pretty simple, so it’s speedy, but there’s room for a little mechanical tooth.

Option 2 is something in the Cortex family. The idea of the size of dice matching to effectiveness is very intuitive, and the trick is all in how pools are built and how rolls are used. More mechanical versatility here, but also greater risk of feature creep.

Option 3 is diceless fate dice. Use a simple diceless system to answer Yes/No, but then add in a fate die roll (I’d be partial to 2df, but whatever) to reflect the situation. Very easy to do, quite powerful and intuitive, but it would also take him on a path very far from “normal” RPGs, especially in terms of what dice mean. Not necessarily a bad thing, but something to keep in mind.

(Since someone will surely ask, no, PBTA is not option 4. It’s a table lookup system, and while I suspect he’d enjoy that exercise, it seems like a dead end. The parts of PBTA I think he’d respond well to – playbooks and stunt like things – are better represented with Blades in the Dark tech, at least for my needs).

All of which is bubbling in my head. Practically, we’ll stick to D&D. Once he’s comfortable with 5e, that is a game that he can play with people who aren’t me, and that’s valuable. But also, there is nothing this kid wants more than a Magic: The Gathering tabletop experience and the Ravnica Books have only fueled the fire for this. I feel like that setting prompt, plus his system needs could dovetail very well.

The Social Roles

So, up til this point I’ve been talking about GM roles in terms of what responsibilities might be picked up by the game. It is possible that the GM can do less heavy lifting as an authority, entertainer or celebrant if the game is designed to account for that.

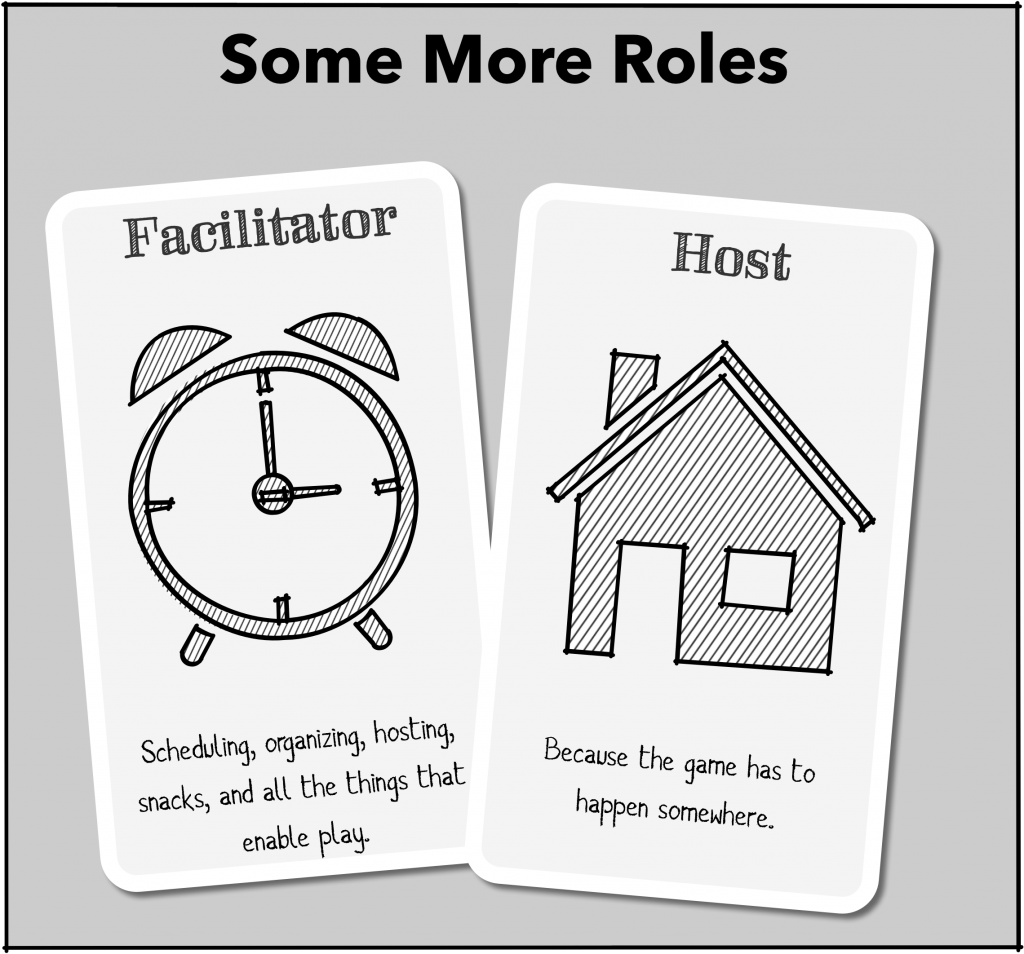

But there are a couple of other roles that traditionally fall on the GM that are probably not something that the game can provide, the roles of host and facilitator. These are both roles that are outside of the game, but are all the same necessary for the game to happen. The facilitator is responsible for the logistics of the game – scheduling it, making decisions about where it will be, who will be in it, making sure everyone has supplies and generally making the game possible. The host role is complimentary (and sometimes synonymous with) the facilitator – providing space to play and all the things that come with that (parking, seating, lighting, a reasonable environment and so on).

As a young gamer, I developed a habit of considering these to be GM’s roles. Sometimes someone else might take responsibility for hosting, but they tended to take on the minimum responsibility, otherwise deferring to the GM as facilitator. Everything else was pretty much on the GM.

The roots of this were not great. At least in my experience, the GM was the reason the game was happening, and if the GM didn’t make it all happen, then the group could just do something else with their evening. Baked in that is an assumption that the group is kind of grudgingly playing, which is a very high school kind of take on it. I grew older and grew out of those patterns of being embarrassed about my hobby and desperate for players, but that habit that the GM had to “make it go” stuck with me for a long time.

That was pretty dumb.

See, while these roles are ones the game can’t provide, that doesn’t mean that the GM is solely responsible for them. Everyone at the table wants to be there, and this sort of load can be distributed. Hell, doing so will make your game better – not only does it give the GM more bandwidth to focus on what she’s there to do, it helps eliminate lingering ideas of GMs being “in charge” of the game in some creepy or unhealthy way[1]. When the work around a game is everyone’s job, it is easier to accept that it’s everyone’s game.

For some of you, this is all probably obvious. It’s possible that you never fell into the bad patterns in the first place. I genuinely envy you that. But for the GMs out there who are running themselves ragged in service of their games, take a second and consider whether you are clinging to these roles out of genuine necessity, or if it’s just a function of habit.

EDIT: Other roles that have come up in discussion of online play and LARP

1 – Because if you see GMing as being about power, you want to claim as many roles as possible to assert that power, even if it’s a pain. Sure, it may suck to schedule things, but if you get an emotional reward from being in charge, then this helps reinforce that. It’s not automatically a bad thing, but it is a red flag – if your enjoyment of play is predicated on maintaining a power dynamic, there is a good chance you are using the wrong tool to find your happiness.

Thanks to You All

Yeah, I have more stuff to write about roles, but this morning my focus is more on rolls as I run around cooking for American Thanksgiving. I am not a great cook, but I am an enthusiastic one, so it is always an interesting experience.

But for this brief window while several things need about 10 minutes before the next stage in cooking I’d like to thank anyone and everyone reading this. Y’all are awesome, and I’m immensely grateful.

Supporting GM Roles

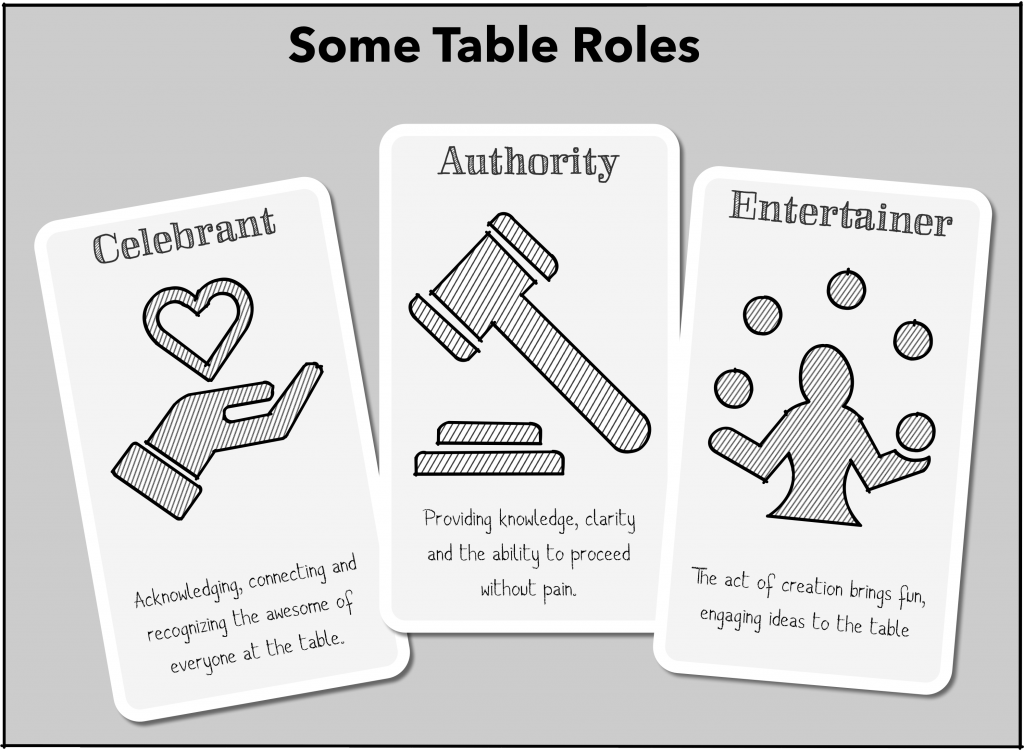

These are not all the roles, just the 3 that I think the GM or system need to pick up. They aren’t exclusive to GMs of course, and there are other roles, but that’s probably another post.

After yesterday’s post about GM Roles, I had a fun discussion on G+ which proposed a model – given any set of GM roles (not just the bog three that I talk about – Authority, Entertainer & Celebrant) you can ask if a game Provides, Supports, Expects, or Ignores that role.

If a game provides that role, then the game is designed to do the heavy lifting for that particular sort of work. A very clear and strictly procedural game might provide authority. A game with a lot of pre-generated content might provide entertainment. A game with rituals and procedures for cross-engagement might provide celebration.

This is usually not absolute. Computer games & RPGs need to fully provide these things, but in tabletop the players still have a role to play. The GM still needs to do something for each role, but the game actively minimizes it.

A game that supports a role provides tools to help with the role, but those tools expect a higher level of GM engagement. Any game with clear and comprehensive rules is supporting authority. A game that provides prompts and seeds is supporting entertainment. A game that has cross-table hooks is supporting celebration.

A game that ignores a role might provide incidental support for a role, but it’s not part of the design or intent. This can be an oversight, but often it’s because the game has specific goals. A very freeform game may ignore authority. A small rules engine may ignore entertainment. A lot of older games ignore celebration.

Obviously, it is something of a spectrum between providing, supporting and ignoring. There’s no precise metric to determine if a game strongly supports or weakly provides a role. That’s fine – the utility of the model mostly relative anyway.

More tricky is the nuance of the difference between ignores and expects.

When a game expects a role, it may look a lot like it ignores it, but where ignoring a role happens because the designer doesn’t consider it important, expecting a role happened because the designer thinks it’s critical, and that it’s what the people at the table are bringing to the game. A game that expects a role might still have a few rules to support that, but only a few – enough to nudge things. Rules that nudge rather than push.

That is, a game might have very loose and simple rules because it expects authority to provide clarity and interpretation in flight. A game might provide little in the way of content or inspiration because it expects entertainment to flow from the table. A game might provide little in the way of celebration because it expects that people are already going to play in a cooperative and supportive fashion.

As such, expectations contain a contradiction (one related to the “fruitful void”, of old) – their lack of tools is a reflection that they may be the *most important* thing in the designers mind. They will also speak to the strengths and weaknesses of any given game.

I find this an interesting lens to turn to my game shelf. It quickly becomes apparent that different games have prioritized differently. If there’s an example of a game that Provides all three roles, I haven’t found it. A more common pattern is that a game provides one, supports another and expects a third.

For example, in my mind, Fate provides celebration, supports authority and expects entertainment. The whole aspect system is in place to make engaging with the content of people’s sheets a critical part of play – playing Fate without celebration requires ignoring a lot of the game. It’s lighter on authority, partly because there’s room for interpretation, partly because it’s a semi-generic engine that expects there may be some assembly required. For entertainment, Fate largely stands back and expects the table to step up – the game is about YOUR characters and what you bring to the table.

This makes it a great game for people with authorial instincts but no desire to play games that feel like writing exercises (*cough*Me*cough) but it also highlights some of the weaknessesof Fate. Expecting entertainment is very demanding, and can introduce blank page problems. For a lot of players, Fate is a better game when it also supports entertainment (with setting material, prompts, sample aspects and so on), and tellingly that is the direction a lot of people have taken things.

Let’s compare that to Fiasco – I would say Fiasco supports authority, provides entertainment, and expects celebration. Some of these are muddy – its authority support is on the strong side, and it has a few rules that might push celebration up to “support”, but I’m of with this general take on it. Playset provide strong, driving prompts for entertainment, and there are enough rules to keep things moving, but lots of space for non-rules on the authority front. Celebration is largely on the players, and is going to make or break the game. This might seem like a gap, but phrased slightly differently, this is saying that the table is going to have as much fun as it wants to have.

On the other hand, there is a common Powered By The Apocalypse mode which provides authority, supports entertainment and expects celebration. The rules are designed to strongly hold authority, but also provide prompts and suggestions as well as tools for structuring the entertainment portion of things, but celebration is expected to emerge from play. Different PBTA games have tweaked this formula in different ways, so it’s far from cast in stone.

D&D is even more interesting to look at this way, because there have been enough D&D versions and derivations that you can see wildly different priorities between versions. D&D that provides entertainment, expects authority and ignores celebration is a model that’s easy to recognize, but also interesting to contrast with 5e (which I would say takes the curious but appropriately middle-of-the-road position of supporting all three, but expecting or providing none).

Ok, so this is a fun toy. Categorization systems always are. But is it of any real use?

For me, at least a little. The problem that is underlying all of this is my desire for a Santorini experience, and this model has emerged as I’ve looked for patterns to help with that. I think explicitly examining what roles a game brings ot the table is going to make it a lot easier to intentionally design to cover for gaps. So this is definitely going into my toolkit, and we’ll see what kind of nails it hammers.

The Role of GM

Saw another thing about the magic of GMless play the other day, and my response is largely what it always is: I think it’s nice, but it doesn’t really excite me.

Saw another thing about the magic of GMless play the other day, and my response is largely what it always is: I think it’s nice, but it doesn’t really excite me.

To be clear, that’s not a criticism, it’s just a statement of taste. Games like Microscope and Fiasco are great, and can absolutely be fun to play. But they don’t scratch any particular itch for me. I enjoy them when I play them, but don’t necessarily seek them out. And there’s no harm in that – our tastes are not uniform, and it would kind of suck if they were.

But this is on my mind because a comment on my Santorini post cut right to the heart of one of the biggest challenges to a “pick up and play” RPG – the GM. There are decent tricks and tools for getting players ramped up very quickly, but the idea of going from zero to GM seems much more daunting.

One of the solutions to this is, of course, GMless play.

It seems like a no brainer. Cut the Gordian knot and remove the problem entirely. I have to respect a solution like that. And more, I acknowledge that for certain games (particularly those that unfold in a procedural manner) it can probably work really well. For these games, there is probably a lot to be said for looking at the kinds of things that companies like Stronghold Games are doing with making games with no rulebook, but which instead make teaching the game and emergent part of the gameplay.[1]

But it’s also a bit of a cheat, depending on the job you think the GM has. Critically, the GM is often the subject matter expert on the game in question. Obviously, this may not be the case for established tables, but we’re talking new players and new games here. In this case, the problem we encounter is that the GM’s lack of expertise is the thing we need to replace. That may not seem like a big deal until you consider that many GMless games skirt this problem by including a “facilitator” role.

This is not a bad thing: Every game is more easily learned and played when someone at the table is a familiar with it, so making space for that person is good design. But since we’re explicitly talking about picking up a game quickly, that option isn’t available to us. This doesn’t remove GMless games as a solution, but it means they’re in the same boat with everything else – looking at the question of how to convey what’s necessary in a playable fashion.

So, we’ve lost the silver bullet, but it’s highlighted something very useful. If we’re not going GMless, what does that mean?

People have a lot of answers to that question. I could fill pages with the differing interpretations of what a GM can and should be[2]. Hell, half the reason I shrug at the argument for GMless play is that they often rest on definitions of GM driven play which are very different than my experience or taste.

I can’t pretend to offer a comprehensive list of GM roles, but I do want to focus on what I consider the big 3, authority, entertainer and enabler.

The GM as authority is the expert on and boss of the game. She makes the choices about the game, enforces and interprets the rules, implements rule zero(or doesn’t) and is generally in charge. There is a lot of potential nuance around where that authority comes from, but the role is pretty simple. The advantages of this role is that it keeps things going and provides clarity for everyone at the table. The disadvantages are that this is a SUPER abusable dynamic, and a lot of game horror stories come from it going awry.[3]

The GM as entertainer is one that we tend to both ignore and take for granted. Classically, the idea is that the GM is generating (or using existing) content for the players to bounce off of and have a fun time. For many GMs, this is the best part. It’s an outlet for their creativity which they delight in sharing. They delight in it so much that we tend to overlook that this is work. This becomes relevant when we talk about new players – this is a hard role to step into from zero.

The GM as enabler (which sounds less weird than “servant”, the term I actually use in my head) is there to help the players along to the thing they want. I think of this as the most important role, since it is most closely tied to the table’s fun, but it’s also a tricky one. To do it successfully requires understanding what the table wants enabled, which is sometimes murky. Classically, we also have a problem with this role because it is the least well supported in our games and history.

EDIT: in comments, Fred suggests celebrant as a better name for this, and he is 100% right. Not only is it less weird, it also allows all three roles to be nouns (authority, entertainment and celebration) much more easily. As such, that’s the term I’ll be using form now on.

Now, these roles can be complimentary or contradictory from game to game and table to table. A GM might have strong authority and great entertainer skills while ignoring enabler responsibilities entirely, and her table might have an amazing time. Another GM might not entertain at all, but run a tight (authority), player-focused(enabler) game that everyone enjoys. There are many paths to a great game, and no one right route.

But I mention them in this context because it occurs to me that perhaps the trick may be to stop short of going GMless, and instead opt to explicitly narrow the GM’s role to something smaller and more specific.

The raw form this took when it popped into my head was “hey, what if the GM wasn’t tasked with coming up with content, but instead was just expected to learn some tools for helping players do cool things?”. I’d now restate that as “ok, can we teach the enabler role out of a box?”, and the thing is, i think we can.

In fact, I think we could teach any of those roles out of the box. The problem only becomes daunting when you try to teach more than one of them.

So now I find myself thinking about the differences in how i would teach those roles, and it highlights one more key point: you are under no obligation to stop at one role. I mean, feel free to do so – if you want to design your game so the GM’s role is pure enabler, then feel free. Just make sure you figure out how to make it fun for the GM.

But you can just as easily start from one role as the one to learn out of the box. And just as players will gain mastery and depth, so too can the GM. Other roles and responsibilities can be layer on after that first session of play has hooked them and left them hungry for more. THAT is when you can start laying it on thick.

Not sure if this helps anyone but me, but I am definitely feeling a step closer to a workable model here.

1 – Though this sounds great on paper, the one downside I’ve found to this approach is that I’ve only seen it work for fairly simple games. The idea is a good one, but I am not yet sure how it scales.

2 – But here’s one crazy one: it is pretty dumb that we treat the role of GM as the same from game to game rather than a function of each game-as written and game-as-played.

3 – This does not make it all bad. A table can knowingly grant someone authority because they trust them to make it worthwhile, and that combination of authority and trust can make for AMAZING play. But that takes a lot of work, and it not for everyone, which is fine. But I want to mention it because for many people, GM authority is automatically toxic, and I disagree with that notion pretty strongly.

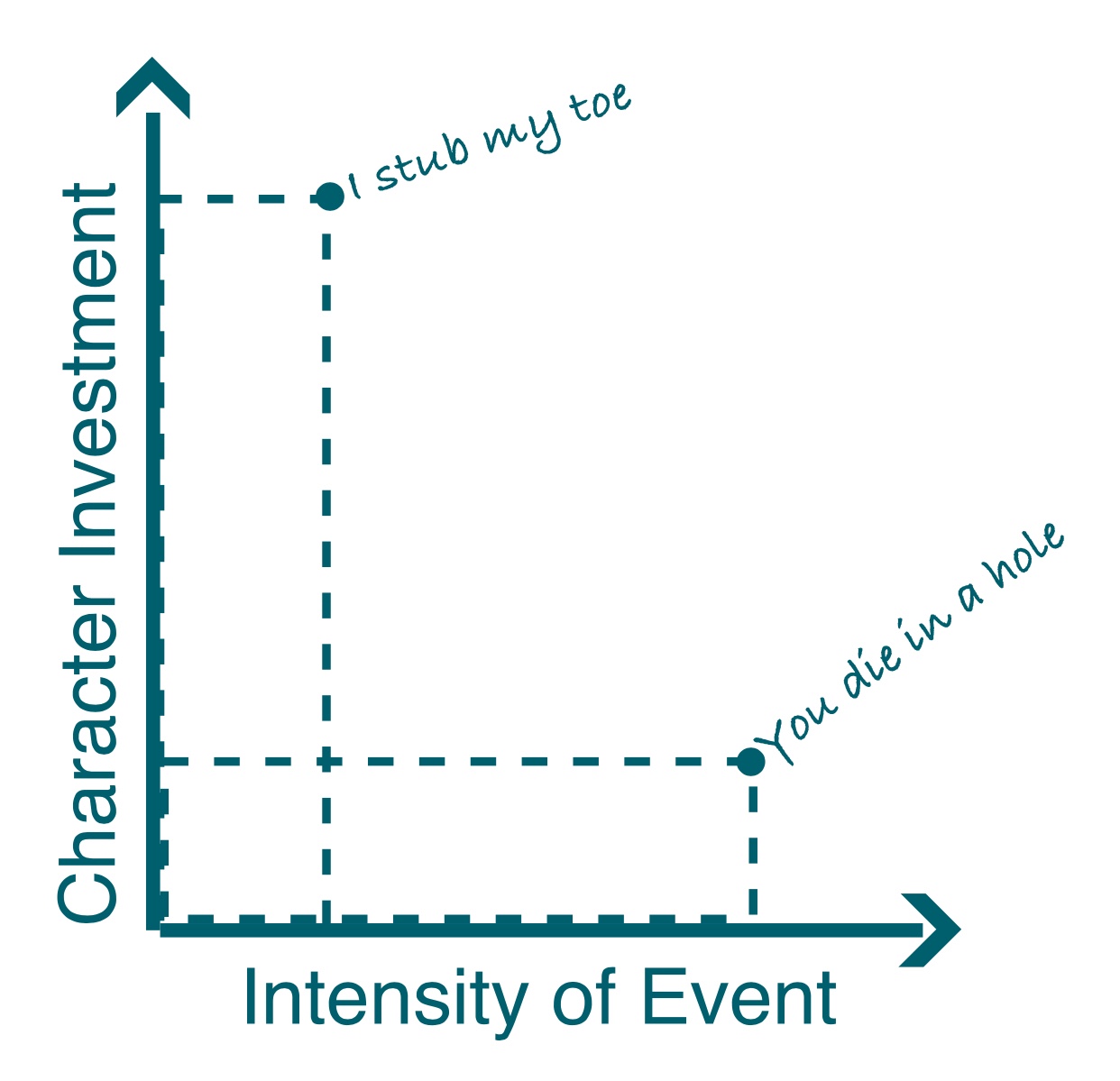

Investment vs Escalation

I was thinking about TV shows and the easy trick of upping the stakes to increase viewer investment, and how it’s kind of cheap. We all know this: it is a lot less work to have the plot endanger a bunch of kids than it is to spend the time to get us to invest in a smaller problem. Trauma is a super useful shorthand when time is short.

We have a version of this in RPGs, and it has a similar tension, but is maybe a bit more confusing. See, the TV model only sucks because writing characters we care about is the harder but better option, so forced escalation feels cheap. RPG characters are a bit more nuanced.

At first blush it would seem that if you are playing with a high level of character investment, forced escalation is awkward. But what if a high level of character investment is something you reach quickly? Playing a character over time to explore them is one valid mode, but so is slipping into a new character and buying in IMMEDIATELY. For that player, the “forced” escalation might just be jumping to the good part.

And, of course, some players are more interested in the escalation (or rather, the issue behind the escalation) and for them a *lack* of character investment provides some emotional protection (or distance, for authorial purposes),

Obviously, taste is rooted so deeply in this that there is no one good solution, which is as it should be. But I mention it because I sometimes see people get confused about how people could *enjoy* certain types of games (usually those with fairly bleak content), and the instinct is to look at the content for explanation. I suggest that if you can shake free your assumptions about character investment, it might be easier to make sense of.

Personally, my tastes skew towards investing in a character over time and seeing where play takes them. This makes high escalation, short term play something I have to really shift gears to enjoy, and I’m not always successful. But I get that that’s my bag, and thinking about stuff like this is how I made peace with it.

(Semi experimental post. Did it all on my phone while sitting in a waiting room, so apologies for any weirdness.)