So, we’ve started a new experiment in gaming. A lot of us are parents of young kids or have time consuming jobs, so scheduling has been a bear. The solution we’re trying is to stake out specific, consistent time slots (like the 2nd and 4th Friday every month) with the simple rule that there will be gaming during that slot, and we’ll play with whoever shows up.

That creates certain demands in how the games get structured. The rules need to be on the light and fast side, and the setting needs to support a rotating cast. There are a number of ways to approach both of these needs, but in this particular case, I opted for an urban game (with some twists) played with Dungeon World.

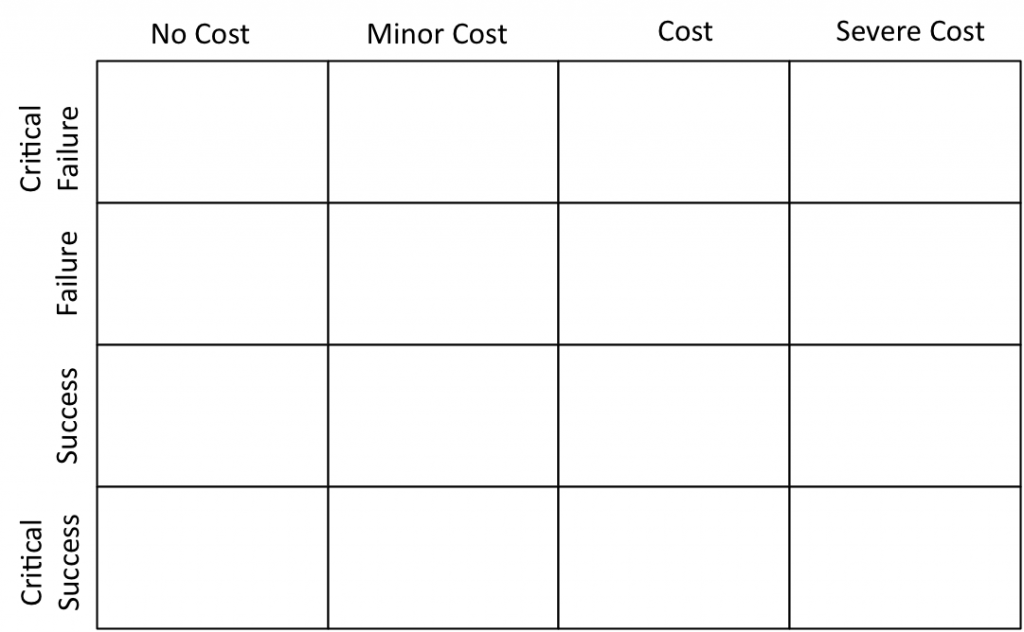

My ongoing struggle with Dungeon World is something I’ve written about before, but this time I shifted up my approach, and tried to treat it as a diceless game that happens to have dice, and that worked out pretty well, though I’m still getting the hang of it.

So, the game itself started with the idea of two different cities in two different places getting pushed together, producing a weird and impossible geography that had transformed both cities and still needed to be discovered. We discussed it a bit, with the big question being whether this merging was overt or secret, and we opted for secret. In conversation it refined a bit and the net result is that the two cities connect in strange places (roads, alleys, doors) which most people can’t see, but some people can, and these people have realized that there’s a lot of potential in mapping this out, and are also discovering that there are other places that have been pushed into the equation (providing for little pocket worlds and dungeons within the context of the two cities). With about that much background, we launched into chargen.

We had 3 players with varying degrees of experience. One had played and run DW, one had played it and one was only vaguely familiar with it (though all 3 were experienced gamers). Based on twitter feedback, we limited chargen to the base classes plus the Barbarian, and the players went for Fighter, Wizard and Thief.

Dogan, the Neutral Human Fighter was all hard eyes and shaved head – scary as hell but not the sharpest knife in the drawer. His signature weapon was a huge, versatile hammer which we later determined had a head made of elderglass, which made it ring like a bell when it hit, giving him the moniker “The Bell Ringer” and proving a source of numerous puns.

Huge ended up being very interesting – it adds the keywords “Messy” and “Forceful”, neither of which have mechanical benefits but which add a lot of color to outcomes, which was in turn pretty potent.

Jack, the Neutral Human Thief, was pretty much what you expect from a thief. The thief’s chargen decisions are a lot less visibly interesting than other classes, which is curious in its own right.

Urvudor the Neutral Elf Wizard hit the point of making some decisions about his character (armor or books) that needed some clarity, so we shifted gears to game background for a bit.

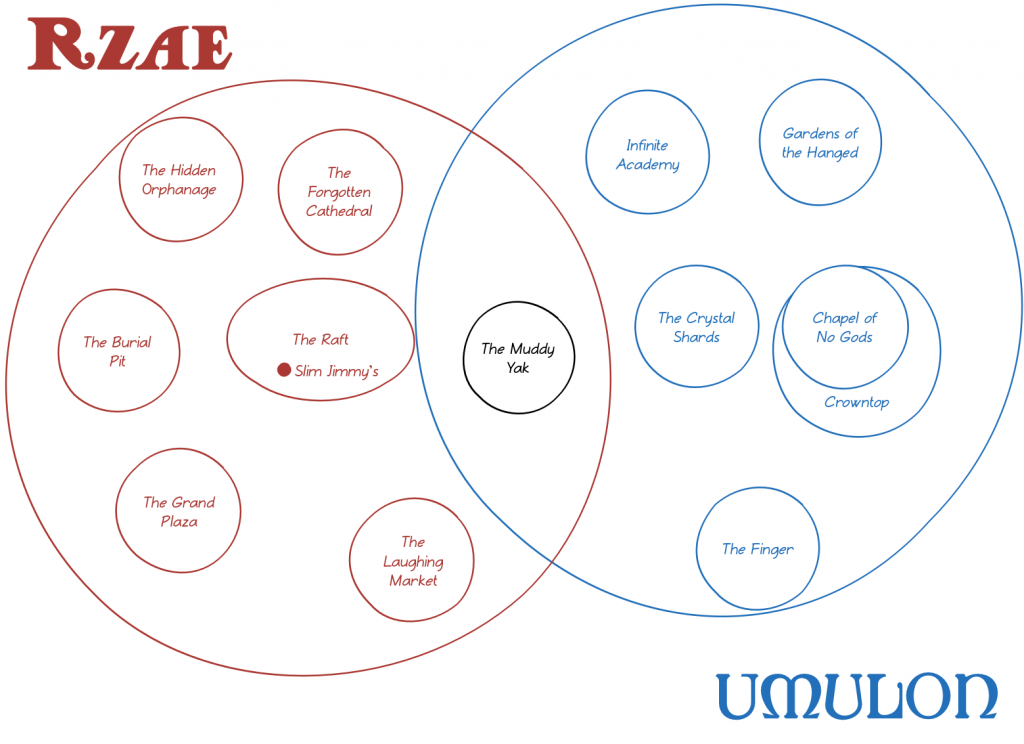

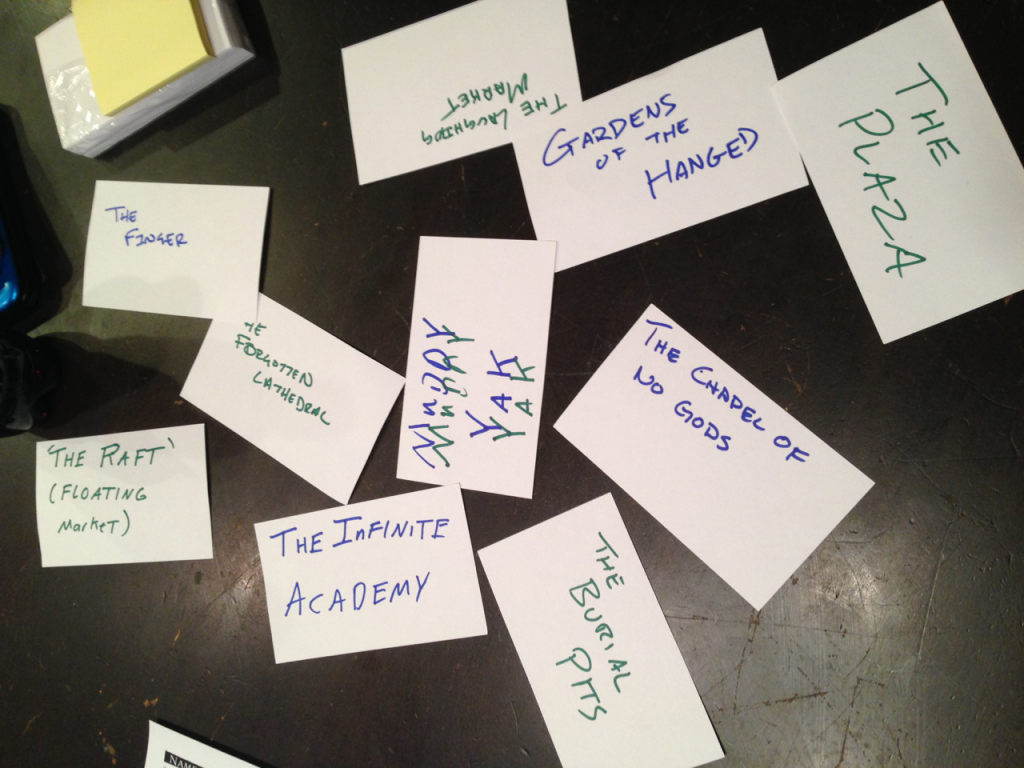

At this point, we knew there were two cities, so I put out two index cards, one for each city, and asked each player (including me) to name one city element. After that I hit people up for vowels and consonants, and we named the cities. In the end the two cities were:

Rzae (Pronounced “Zay”)

- Canals

- Huge Central Square

- Plague Doctors

- Built atop ancient graves of indigenous folk

Umalon

- Sky Towers

- Shadows and Fogs

- No Dwarves

- Elderglass

After that, I handed out two cards apiece (including myself) and asked everyone to write down one thing from each city. For ease of tracking, we did Rzae in green and Umalon in blue, and produced this spread:

Rzae (one extra because the Plaza rolled forward from the last round):

- The Grand Plaza

- The Raft (floating Market)

- The Burial Pit

- The Laughing Market

- The Forgotten Cathedral

Umalon

- Gardens of the Hanged

- Chapel of No Gods

- The Finger

- The Infinite Academy

I also asked for an Adjective and Animal and got The Muddy Yak, the bar that is in a space to true overlap between the two cities (we decided that weird places where things are more mushed together are called “knots”). It used to be a bakery in Umalon and a bar in Rzae, and now it’s got beer and scones (as well as rooms for a very rarified clientele, since only mappers can even find their way into the place).

With this information, Urv decided that he’d come from the Infinite Academy, so he was more of a book wizard. It was also at this point that we determined that bell ringer was elderglass, even though Dogan was from Rzae, where there is nominally no elderglass, which ended up being the first of a few curiosities about the history of both cities and the story of the dwarves.

Some discussion of the group’s backstory also revealed that the law enforcement in Rzae were the Crow Knights (or Crows), dressed in black iron plague masks and armor. Conversation made it pretty clear they were going to be a big part of a front.

We started the session from the traditional position of “you’re broke, now what?”. Urv’s stipend from the academy had run out, something he noted as he commented that the meal they were all eating was the last of his funds. This lead to some wonderful RP around food-possessiveness which became something of a theme as we went forward. The good news is that Urv knew the professor of Dwarven Studies at the Academy (Dwarves had once existed there) who would pay handsomely for real Dwarven artifacts. They figured they could buy some knicknacks in Rzae(after some discussion deciding to get some Dwarven Fighting Steins) and sell them in Umalon. The problem was, they needed to get together the scratch to get the items,

Enter Slim Jimmy’s Rare and Delightful Items of Great Harm. It came out that Slim Jimmy, a dwarf. sold weapons in the Raft. He was largely legit, and a lot of his business revolved around giving fancy looking weapons fictional long histories when buyers had deep purposes. He also had a standing (and steadily increasing) offer to buy Dogan’s hammer. Slim Jimmy, it turned out, had some excellent Dwarven fighting steins, but he also needed something. He showed the team a Maine Gauche in a material and style he did not recognize, and said he would happily trade the steins for the matching sword.

Urv, of course, recognizes the weapon as one carried by one do the Godless Cavaliers, the guardians of the Chapel of No Gods. So he suggested they take the gig, and the group set off to plan in private.

And this is where things took an interesting turn. Up to this point, there had been a few rolls (mostly spouting lore) but we’d been feeling out the characters and setting up the situation, but only light pressure. This changed when the system raised it’s head – they wanted to grab a boat to converse in private, which required some trivial amount of coins (this was on the Raft, after all, a jumble of floating markets) so the thief went to pick a pocket and the dice came up snake eyes.

So, it was on.

So the big, burly dude grab’s Jack’s arm and starts yelling “Thief, thief!” and his buddies start descending. Dogan manages to rush in and “Accidentally” knock the big dude into the drink, allowing Jack to make a break for it. Urv attempts to offer some misdirection (“He went Thataway!”) and failed impressively, but resolved the matter with a judicious application of Charm Person. Dogan’s next attempt to help smashed a hole through the raft they were on, which he fell through and began drowning. I adjudicated it as a defy danger with +con and -Armor, but in retrospect, It should have been just con, with “Lose your armor” as a 7–9 outcome. Learning! Eventually there was glowing rope, a small mix up, and a rescue. Oh, and Jack? Rolled a 12 on her getaway, came out literally smelling like a rose with money in her pocket and her Alignment XP award. Bastard.

Anyway, a great scene that really just flowed from the dice, which was good to see, because it made me a little bit more comfortable trusting the dice, and a little more willing to push for rolls.

And damn, 1500 words so far. Let me wrap up there for now and pick up the rest tomorrow.

First, pack a power strip. This is one of those things which is absolutely common sense once you start doing it, but if you haven’t done it, and you have tried to figure out how to charge your various devices in a hotel room, then you understand the need. I use one of these because it also has USB ports, which reduces the number of adapters I need to carry. One warning: if you have an iPad or similarly large device, make sure the USB ports are 2.1 amp, otherwise it will pretty much never charge.

First, pack a power strip. This is one of those things which is absolutely common sense once you start doing it, but if you haven’t done it, and you have tried to figure out how to charge your various devices in a hotel room, then you understand the need. I use one of these because it also has USB ports, which reduces the number of adapters I need to carry. One warning: if you have an iPad or similarly large device, make sure the USB ports are 2.1 amp, otherwise it will pretty much never charge. The value of the travel tray is probably obvious, but the next thing may not be: Packing Cubes[2]. It used to be these were a rare item that only business travelers knew about, but they’ve gotten a bit more mainstream. If you haven’t used them, they seem counterintuitive – pack your stuff into containers, then pack it into a bag? MADNESS!

The value of the travel tray is probably obvious, but the next thing may not be: Packing Cubes[2]. It used to be these were a rare item that only business travelers knew about, but they’ve gotten a bit more mainstream. If you haven’t used them, they seem counterintuitive – pack your stuff into containers, then pack it into a bag? MADNESS!