When I talk about threads I want to dig up, this is often the first one people mention, so I have opted to rescue it from the pits of twitter, clean up the worst excesses, and turn it into a post.

I have been, in bits and pieces, thinking WAY too much about food in Blades in the Dark. John did a great thing in Blades (which most such fantasy cities skip) of at least acknowledging that food is a thing that must come from somewhere, so there is a space for it.

As i got thinking about it, I think the trick is that there are two elements missing here – the starch, and the fat. The starch (wheat, corn, rice, whatever) tends to make for signature elements of a cuisine – bread, noodles, tortillas, dumplings and so on.

The fat, of course, is for frying. I mean, it’s got other uses too, but trying to imagine vibrant street vendors without frying just seems sad.

So where do those things come from in Duskvol, and what form do they take?

Working backwards from theme, there absolutely needs to be something that can be made into gruel, but that doesn’t narrow things to much. I admit, I could easily visualize dark rice paddies as the farms of Duskvol, so there’s a lot to be said for a grey, shadow rice.

Another solid option is the potato, and I gotta admit that it would feel kind of apt to revive the Lumper in Duskvol, since it’s a foodstuff that helps sustain a certain flavor (pardon the pun) of poverty.

Potatoes are also subterranean, so the idea of taters that grow under fragmented starlight just kind of feels right. And they can be gardened, which opens the door to rooftop gardens, dirt smuggling and veggie poaching.

Potatoes also are potentially incredibly diverse, so ranges of colors and breeds can be a point of pride, interest and competition. So, I think potatoes kind of win as the native default.

(Sidebar: Goats are a potential food source, but my sense is they’re more valuable alive than dead. That said, I am pretty sure that Duskvol’s cheese is amazing, and deserves much more attention).

Before I get to oil, there is some question about cooking method – I have inferred a very stereotyped British sense of cooking as the default in Duskvol, which is to say, a LOT of boiling things until they’re food.

And that’s fine as far as it goes, but there’s plenty of goodness to be had there, and potatoes play nicely with that (and with fish/eel and chips, as I think about it). So, lots of pots and pans in Duskvol, but what about ovens?

There’s no Technology reason why there would not be ovens, but I’m not sure how much there is to bake. Putting a pin in that to come back to.

So, let’s talk cooking oil. One reason it is on my mind is because there are a lot of really good ways to prepare eel, and frying is in that list. And to come back to working backwards from theme, I want Eel & Chips.

The thing is, we don’t have a huge amount of Dairy (we have some) and crops are not so abundant as to suggest a great option. Of course, there is a lot of Leviathan oil, but is it food grade?

The answer is, I suspect, “Probably not, but safety standards have no place in Duskvol”. I’d be inclined to suspect that when leviathan is rendered, there’s a lot of waste product, and “inert oil” is one of those products which some enterprising soul found you could cook with.

It probably has a cooler name than “inert leviathan oil”, because canola. Maybe just “Red Oil”, since it has a bit of a tint to it. Staple of cooking. Probably a lard version of it as well, for all you “you’d best believe it’s not butter” needs.

As with potatoes, other options exist. This is just about defaults and signatures.

Ok, we’re starting to get somewhere here. I can envision a menu with more than 3 things on it. So the next question is probably flavor.

Salt is probably pretty ubiquitous. It’s non-agricultural and preservative, so I am pretty sure the city uses a ton of it.

Red Oil probably has its own distinctive flavor too. Not sure what – don’t actually don’t want it to be something squamous like “pennies”, so I’d maybe say it’s got a little bit of sharpness to it – an acidic edge despite not being acidic.

Since we’ve introduced potatoes and the idea that root vegetables might thrive a little bit more in the dark, that opens the door to a pair of magical friends – onions and garlic (and all their ilk).

Beyond that, I suspect that a LOT of the radiant farms are actually growing spices since so many come from flowers, since I’d wager the profit margins are MUCH higher. Now, this suggests something interesting.

Radiant Farming started in or near Duskvol, so they have a lot more of it than other places. Which may mean that Duskvol is a major spice producer. Now, while this would mostly be for export, it would mean spices would reach the streets more often than you’d thing.

(Oh! And turmeric! It’s a root! That’s another street seasoning)

So, we have some “local” flavorings (garlic, onion, turmeric, salt) and access to a wide diversity of spices with no rhyme or reason to them. Which suggests to me that DuskVol food tends to be strongly and erratically over-seasoned.

And since food shapes words, a “Duskvol Curry” means something whose contents are unknown, unknowable, and there’s no real way to tell if it’s going to be a good surprise or a bad surprise, or both. Because both the contents and the spices are “what’s on hand?”

It also means Duskvol has a high opinion of their cuisine because they have THE MOST spices, because they don’t quite get the notion and ultimately treat every spice like a different version of garlic, and the right answer is always “more”.

It also helps that the city has a tendency to obliterate your sense of smell.

So, we almost have enough for our fancy sunday dinner, but let’s come back to look at the protein. Eel is great, but let us consider the mushroom.

Mushrooms are AMAZINGLY diverse, and practically magical already, so there’s a LOT to be done with mushroom that can fill gaps.

(In our game, the coffee equivalent – called “shoe” because it’s boiled in a pot that may well have a boot in it – is made by boiling mushrooms)

So, practically, I want Mushrooms to be able to slide into that Protein slot a little. Other slots too, but I kind of want a Mushroom Roast to be a thing. And we have an easy way to do it – remember that Leviathan Waste Product?

It grows large pale and red mushrooms that bleed.

The bleeding (and also the singing) can be a little creepy, but for most people, they only see them once the’ve been harvested and cut up for presentation at the butcher. Yes, the taste is never great, but you get used to it. Along with potatoes, it is absolutely a food of the poor

Not to say the rich don’t eat mushrooms – they absolutely do – but they eat higher class mushrooms.

And with that, I now can actually see how a Duskvol family might actually make a special Sunday dinner that’s not the same as every other bowl of jellied eels they’ve ever eaten.

Lots more fun to be had in this space, but this will do for now.

A brief follow up

Ok, one last thought inspired by @sandrayln – flowers require bees. Beekeeping in Duskvol is INCREDIBLY IMPORTANT AND VALUABLE, since radiant farming would rely on it. So

1) beekeepers are all badasses

2) A Honey Heist would actually be a thing

So, I now think that pollination is the big difference between radiant farms, because I too love some of the alternate ideas. Also, I admit to wondering if ghosts can spread pollen.

Somone also pointed out that there are real world pollenating moths, and DAMN if that doesn’t seem on point.

Other thoughts

- This thread actually directly inspired another post of mine.

- Thinking about the Leviathans has got me to thinking about Leviathan Ambergris, which is a delightful/terrifying idea.

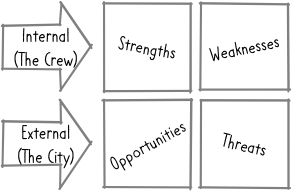

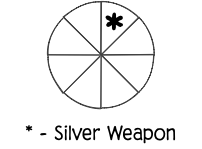

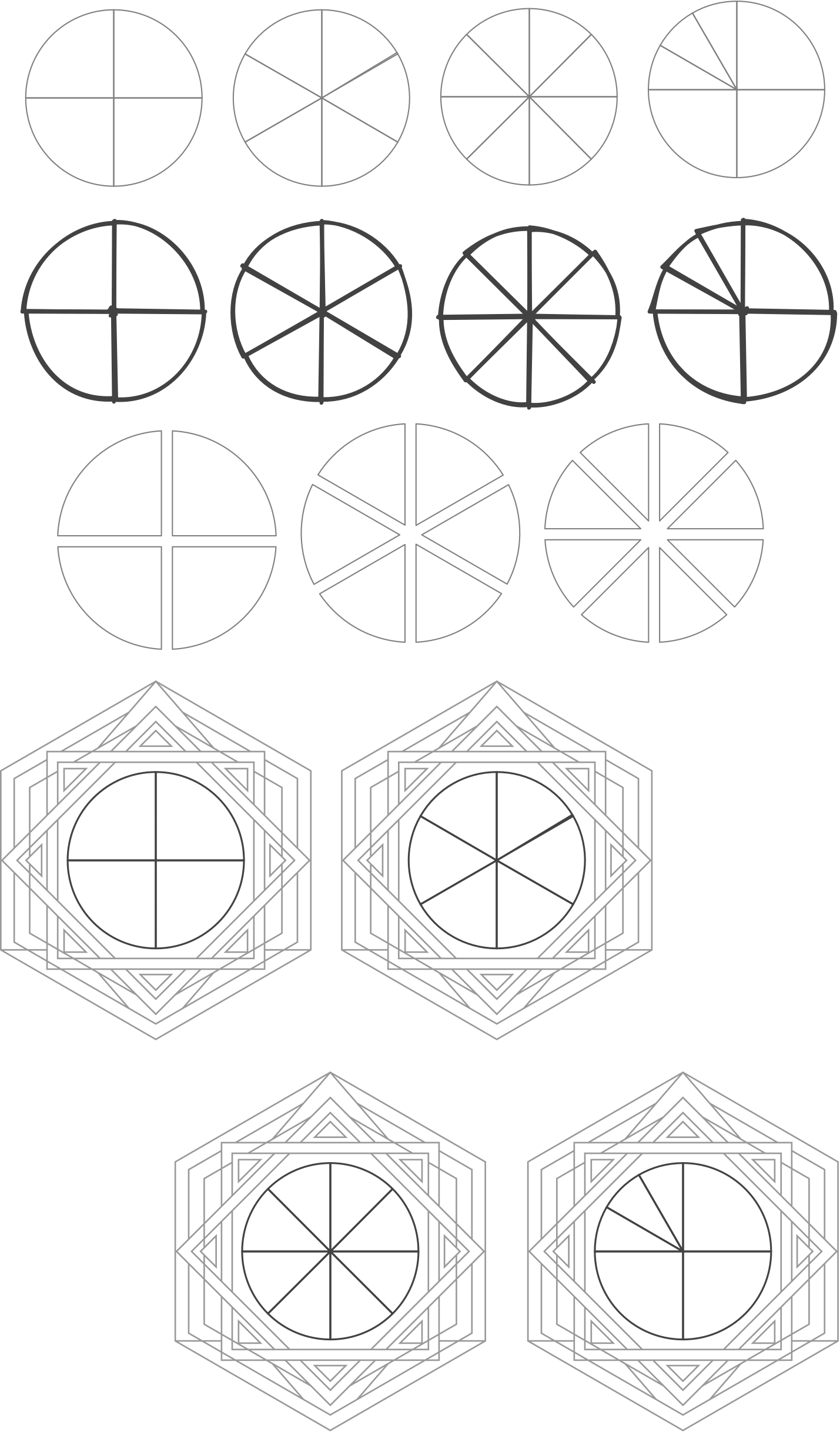

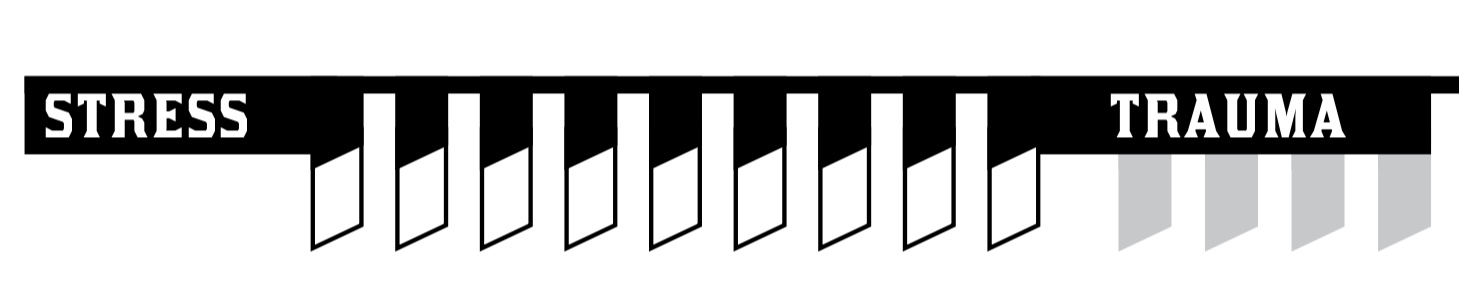

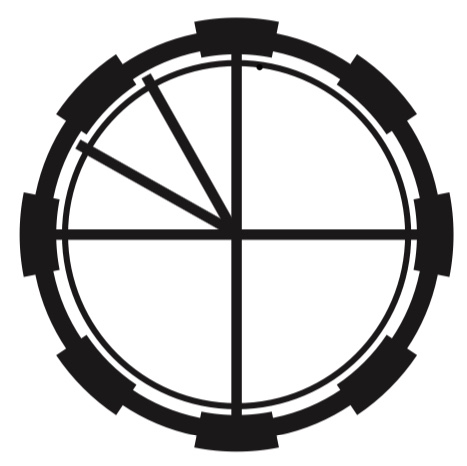

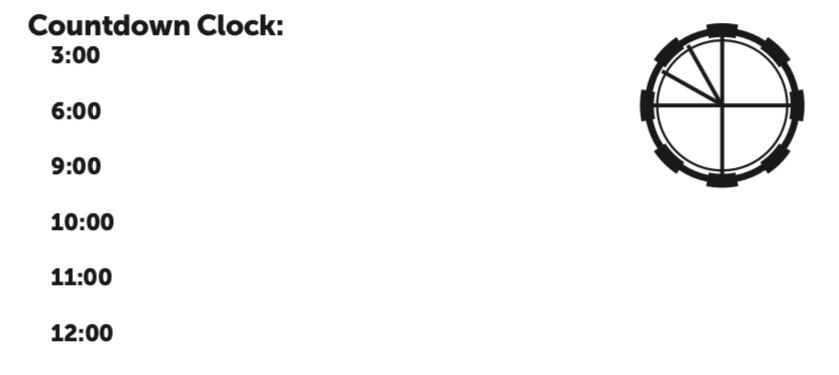

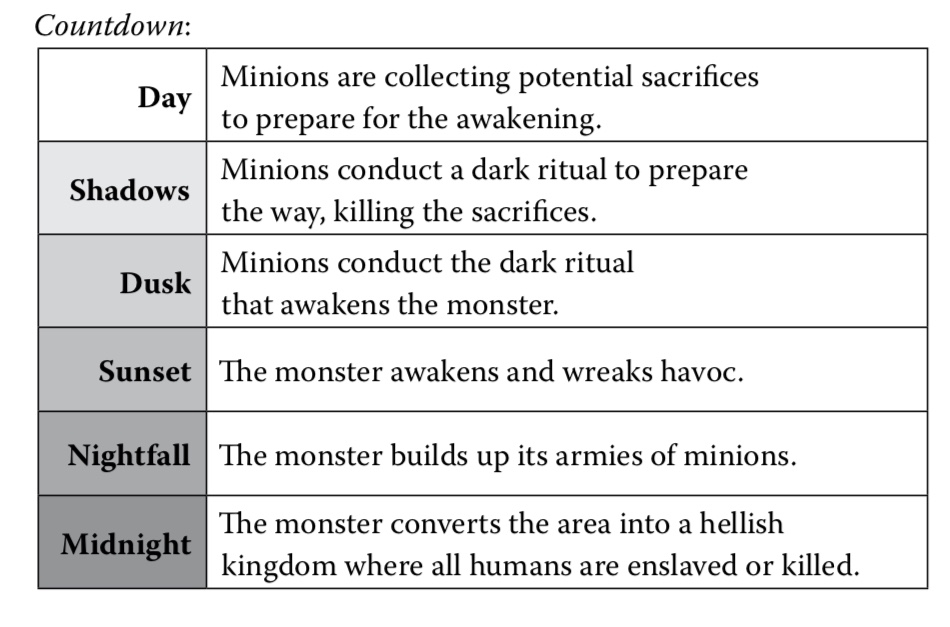

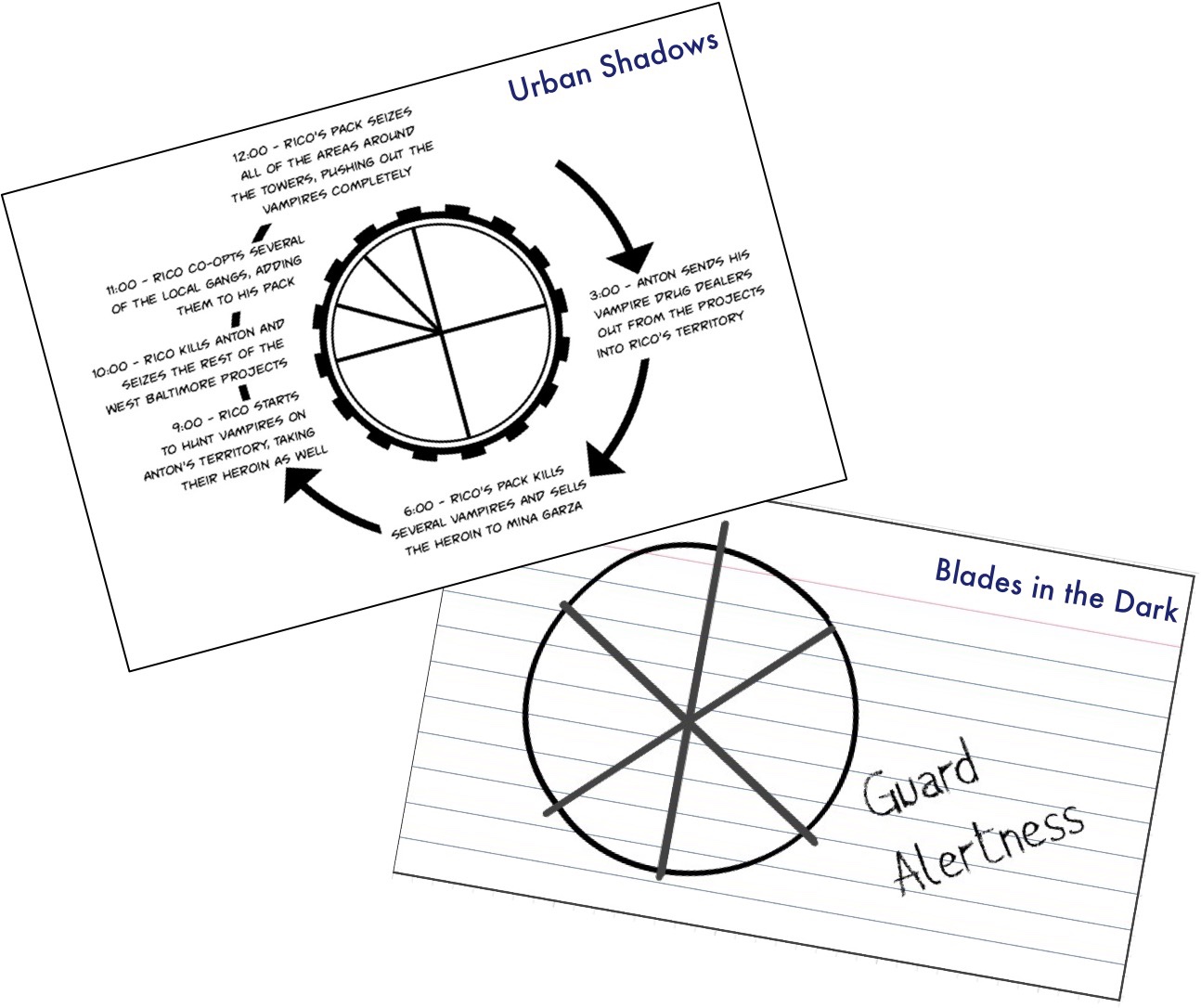

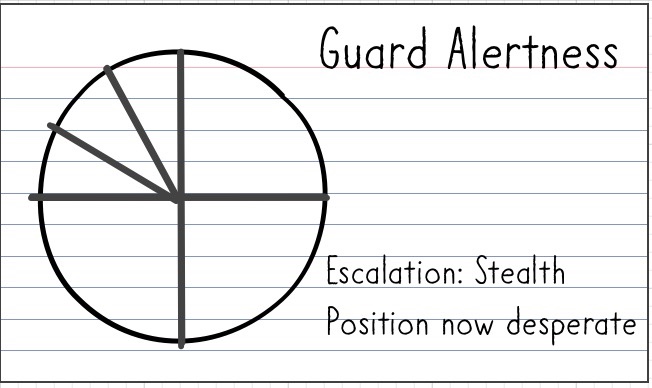

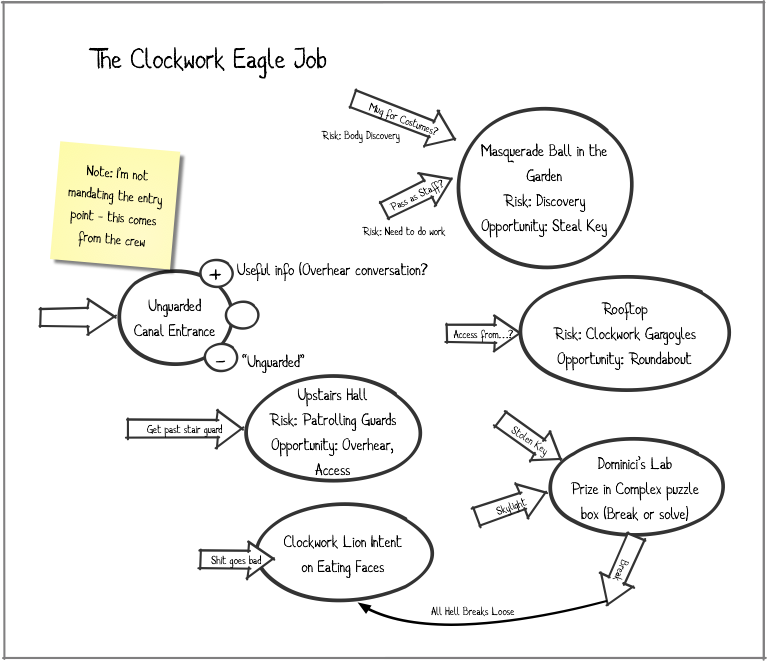

This is a pretty good model. Good enough that I want to fiddle with it, but that’s another post. But there is one element of it I did not like at all, and that is the physical presentation of it, and it illuminated something about clocks to me.

This is a pretty good model. Good enough that I want to fiddle with it, but that’s another post. But there is one element of it I did not like at all, and that is the physical presentation of it, and it illuminated something about clocks to me.

As I work on the Grifters writeup, I occasionally get sidetracked into a pair of other gang playbooks that mostly exist in my head, one for artists, the other for revolutionaries. Both of those other playbacks really appeal to me as things to play, but they suffer from one key disconnect with Blades – the question of how to get paid.

As I work on the Grifters writeup, I occasionally get sidetracked into a pair of other gang playbooks that mostly exist in my head, one for artists, the other for revolutionaries. Both of those other playbacks really appeal to me as things to play, but they suffer from one key disconnect with Blades – the question of how to get paid.