(Yes, we have since used the name elsewhere, but I don’t have it in me to search and replace the whole doc, so you get the classic name. Suggestions for new names are welcome in comments. Also, I forgot – an explanation of why this is now getting posted.)

![]() A game of action, espionage, and the prices to be paid for both.

A game of action, espionage, and the prices to be paid for both.

Consider, for a moment, the similarities between a superspy movie and any other action blockbuster. Both have supremely competent protagonists doing an array of awesome things, facing down enemies ranging from the frightening to the ludicrous. There’s gunfire, explosions and no small amount of sexiness. On the surface, they seem vary similar indeed.

The difference is small on the surface, but reveals much – the superspy must not exist in a vacuum. He carries the burdens that brought him where he is and the ties tot he world which might be the only thing holding him up (or might be the garrote around his throat.) He understands that his actions don’t exist in a moral vacuum, and in a job which demands he trust no-one, he must trust that the bad things he’s doing are for the right reason. He has a moral core which he must ignore for the sake of the job, but which he must never abandon, lest he become the enemy he faces every day.

Compared to those pressures, gunfights with terrorists and ticking time bombs are just another day at the office.

Quick Conversion

DRYH concepts map to DTYB concepts as follows: The GM is referred to as Control, which is also a shorthand for the agency the agent works for.

Discipline is now Experience

Madness is now Support

Exhaustion is still Exhaustion

Despair is now Menace

Hope is now Assets and works a little differently

Pain is now Opposition

It’s worth noting that DTYB is designed with a single player in mind – there are rules for handling multiple agents, but the focus is on a single character, which is why there are no rules for talents – the need to distinguish between awesome agents is not as pronounced.

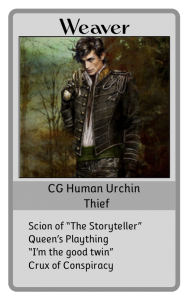

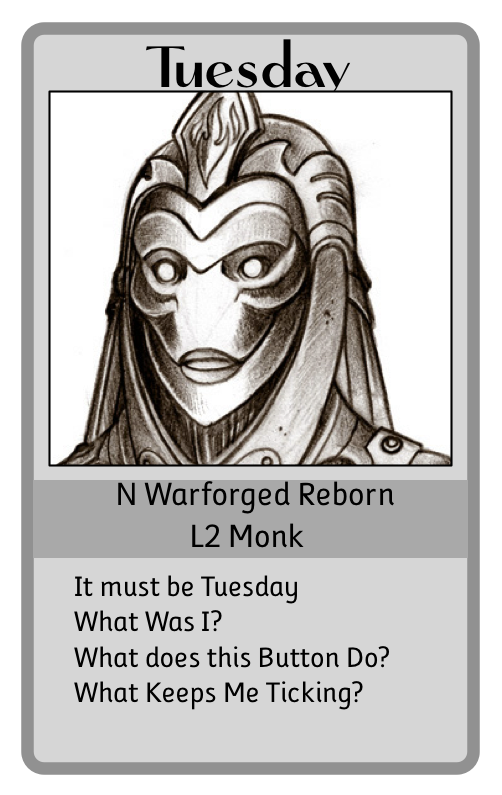

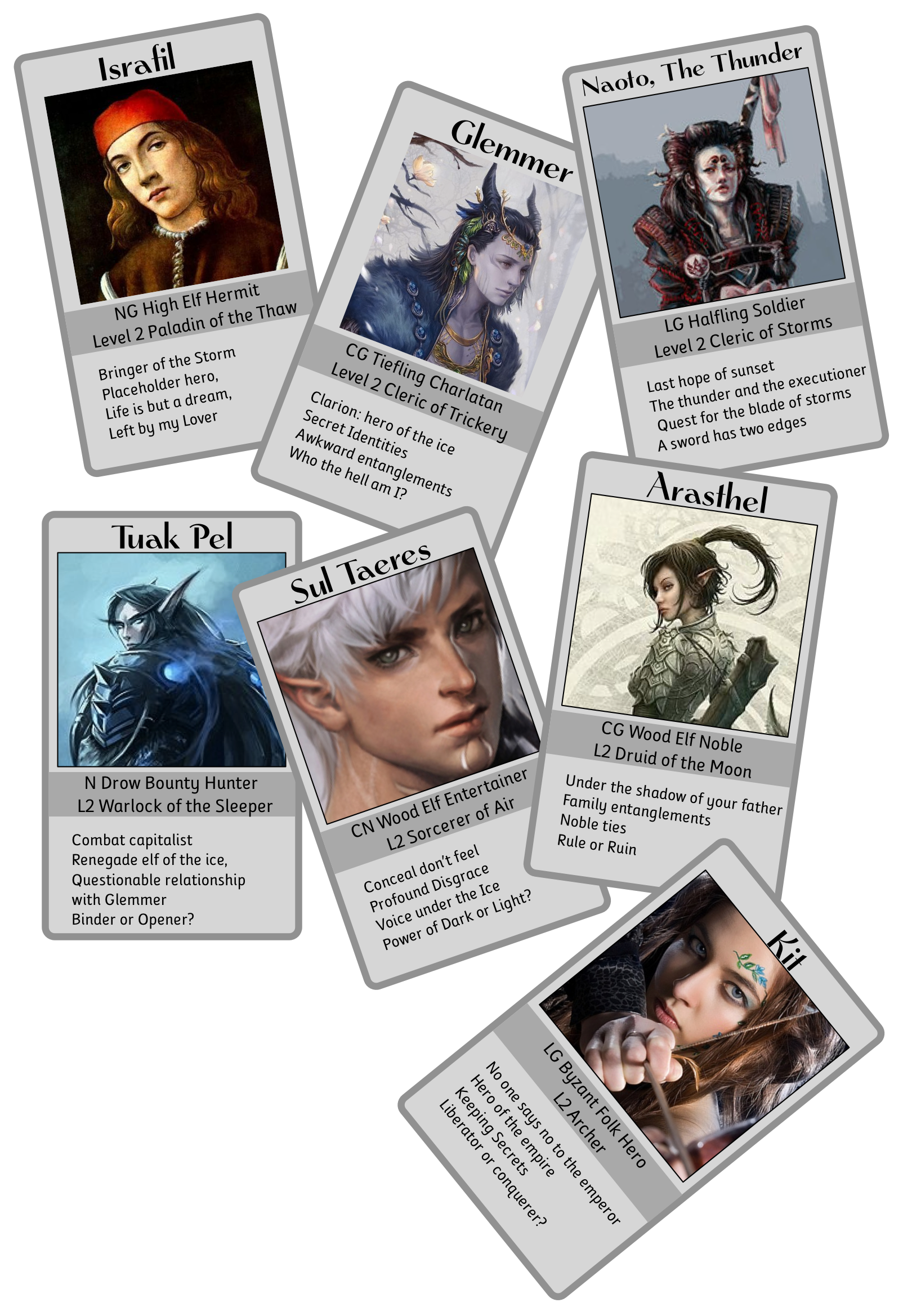

Creating Your Agent

The core rating of an agent is his level of Experience, measured in a number of white dice. An inexperienced, rookie agent might have only one die, while an experienced field agent might have two. Agents with three dice are the supreme badasses of the sort common on the big screen. It’s generally expected that players will have 3 experience dice.

Questionnaire

Who is Control?

Control goes by any number of names, but it is ultimately the organization that the agent (or agents) report to. Control provides the agents with direction, in the form of missions. An important part of any Agent’s story is who he works for.

The Mission

At the outset of any mission, Control (Which is to say, the GM through Control) establishes two things. The THREAT and the OBJECTIVE. The THREAT is the larger problem that must be addressed over the course of the game. In movie terms, this is the danger established early on. Usually something important has been taken (from a formula to a gadget to a nuclear sub) and it must not be used (or lost, distributed or sold on the black market.) There are variations on this formula, and the GM is encouraged to explore them freely, but when in doubt? Something important and dangerous has been stolen, easy as that.

The Objective is simpler, as there will be many Objectives over the course of a game. The ultimate objective is, of course, to address the threat, but it’s never quite that simple. Basically, when a objective is accomplished, the situation changes (because new information is now available or an obstacle has been removed) inviting a new objective. After enough objectives have been accomplished, the threat should ultimately be addresses.

Opposition Pool

Control has a fixed opposition budget which they can use over the course of the game, and the level that budget is at controls how many opposition dice Control can roll in the given conflict. This pool will get higher as the game continues, and some events may be triggered based on this.

BY default, the Opposition pool begins as equal to the Agent’s experience pool. In games with more than one agent, it’s based off the largest experience pool, +1 per additional agent.

Designing objectives

The easiest way to design the objectives of a mission is to start at the end and work backwards. For example, if the super-widget is being auctioned on a private island, then it’s easy to work a backwards. Set up a objective, then ask, “How do they get there?” Foe example

- Infiltrate the island and capture the widget

- Get to the island

- Find the island

Ok, at this point, we hit upon the first real snag – the objective leading to this is not obvious, and that’s where it becomes necessary to start adding detail. We haven’t thought much about the villain yet, and this now gives us a reason to do so. If he’s an evil super agent, how would we find out the location of his lair? Find someone invited to the auction and steal their invitation? Interrogate one of his minions? Maybe he has some exotic habit and shipments can be backtracked?

Any of these are valid answers, and the important thing is to pick one and run with it. Let’s say you go the auction rate.

- Steal an Invitation

- Find who to steal an invitation from

- Find out that there’s going to be an auction

- Investigate an expert on super-widgets

Now we have a throughline for the mission. Agent gets sent to investigate Doctor Smee, an expert on super widgets to find out if he’s involved. Maybe he isn’t, but he’s targeted for kidnapping by goons looking to buy the super widget. Dealing with those goons (or rescuing Smee) reveals that it’s for sale, and their employer has an invite. Clearly, that will require stealing the invitation, probably at a high-end casino, then using that information to procede to recover the widget.

Agent vs. Control Objectives

The very first objective will be provided to the agent by Control, but after that, it’s quite possible that the agent will take the initiative in pursuit of another objective. In this case, the player can lay out the next objective and (if necessary) how it helps lead to addressing the threat. This is part of the framing process, and players have a lot of leeway here, including introducing new elements into the game, but they’re not allowed to skip steps. If a player tries to simply jump to endgame (by killing the bad guy, perhaps), then that’s a fine opportunity for a twist or dead end.

If the agent lacks clear direction, or can’t find a good objective to pursue, that’s when it’s a good time to step in as control and put forward a new objective. This usually takes the form as orders. One handy trick for players – if you want to flag that you’re not sure where to go next, “get in touch with Control” is a great objective.

Twists and Dead Ends

The fact that there’s one throughline does not mean that’s how things will absolutely turn out. Instead, that merely serves as a polestar – providing something to navigate back towards through play.

And this is good, because it’s almost certain that things will go off in unexpected direction once play begins. Embrace this when it happens, and just keep an eye on the objectives – if they don’t feed back to the threat in some way then you might need to step in as Control.

That said, there is nothing that demands that the path from objective to threat be a straightforward one. Usually, the outcome of successfully achieving an objective is fairly predictable – if the agent gets X, he’ll be able to do Y – but sometimes the unexpected happens. It’s entirely possible for the result to be unexpected (a twist) or to offer no further course of action (a dead end).

Twists and dead ends are powerful tools to allow control to pace and direct play, and there are some subtleties in their application. Dead Ends should be used sparingly, in large part because they break the chain of action. Either the agents will need to get a new objective from Control or they’ll need to revisit a previous choice, and if that choice is too far back, it can feel like a lot of time has been wasted. On the other hand, the spy game is not always fair, and a dead end can result from the agent losing a scene without feeling unfair. So here’s the rule of thumb – limit your use of dead ends to the ones which really piss off players. If you’re going to frustrate them without also making them angry enough to take action, then it’s hardly worth it.

Twists will be more common – after all, they’re expected in the genre. A twist occurs when an objective is not what it originally seemed – the information you got points somewhere else, the shipment you intercepted is actually drugs or the like – it should still suggest a new objective, but not the one expected. A twist can steer things towards the throughline, or away from it, and they’re a useful tool for Control to nudge the game with while not demanding a specific course of action.

Running the Game

The objective should provide the basis for framing scenes. It’s possible that there may be only a single scene for a given objective, or it might take several scenes – this is mostly a difference in taste and detail. Since the agent is presumed to be pretty capable, there’s no need for every obstacle and problem to result in the dice being rolled – in fact, dice are less of a measure of how hard a task is so much as how interesting it is. Interesting, in this case, means control can clearly see the many directions this scene might go, depending on the dice.

That is to say, the agent may casually get past the locked door and laser grid, but the dice might come out when there’s a single guard to get past because Control has some cool ideas for how this might go.

When the dice come out, the baseline roll will be between the Agent’s Experience pool and Control’s Opposition pool. Player’s can supplement their roll with Support or Exhaustion.

Support dice take the form of resources provided to the Agent, and mechanically works like Madness dice. This might be a cool gadget, a team of forensic accountants or anything else the agent might be abel to request. There’s no need to justify this, though the player is free to narrate a brief flashback of them preparing this support. A player may add from 0 to 6 support dice to any roll, making support very powerful – however, it’s also a blunt instrument in a job that usually requires a scalpel. Every gadget, every supporting agent, is a risk of revealing exactly who the agent is an who he’s working for. Worse, it inclines the agent to depend on others rather than himself.

When Support dominates, one experience die is replaced with a support die.

Exhaustion is more moral than physical, and represents the hard choices and sacrifices an agent has forged into an armor of indifference. By default, an agent starts with an exhaustion equal to their experience -1. Exhaustion dice may be added to any roll, but when it dominates, the Exhaustion pool grows by one.

Assets

Hope and Despair are well and good in dreams, but int he grey world of agents, it’s all about Menace Assets. The coins used for Hope and Despair are replaced with a forth die color (blue or yellow are best) which are kept in separate Agent(asset) and Control(menace) bowls.

Menace

When control spends a menace die, it moves into the Asset bowl. Control never actually rolls menace dice directly. By spending a Menace Die, Control can do one of the following:

- Increase the Opposition Pool by one die size

- Add a 6 to any pool in play

- Remove a 6 from any pool in play

- Introduce a Henchman with a value of 2. The Henchman increases the Opposition Pool by it’s value in any scene he’s in. Control may only have one Henchman at a time.

Assets

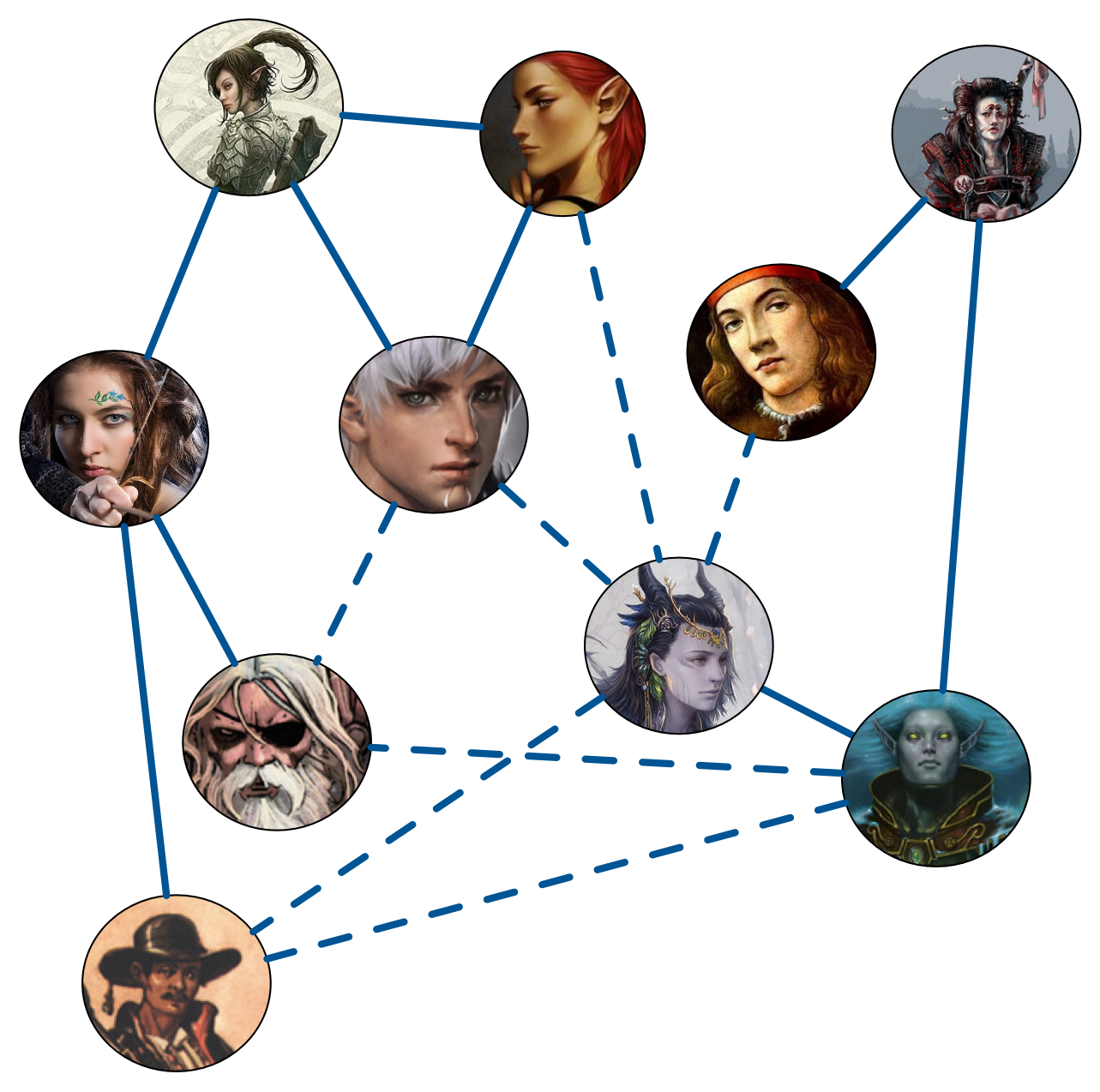

Assets are people – hirelings, assistants, romantic interests and so on. Players may remove an asset die from the bowl by giving it a name and a description (and usually, a role relative to the threat, such as the villain’s girlfriend or a scientist working on the problem). When an asset is created, write the name down on a piece of paper, and record its value (1). Additional asset dice taken from the pool can either create new assets or increase the value of an asset already in play.

Asset dice equal to the asset’s value can be added to any roll, but doing so explicitly says that the asset is involved in the scene. This means that the asset dice can potentially dominate, but it also means the asset is at risk. Only one asset may be added to any given roll.

Sacrifice

Assets may also be sacrificed for beneficial effect. This is declared between scenes, by the agent handing an asset to Control. The Agent may no longer use that asset, and Control has now been given free reign to narrate what terrible thing happens to the asset (which might be death) that inspires the Agent. In return, the Agent may do one of the following:

- Reduce Exhaustion by 1

- Reduce Exhaustion by 0

- Turn a resource die back into an experience die

Control is encouraged to make sure the fate of any high-value assets are handled off-screen because Control has the option of introducing a sacrificed asset as a henchman. If so, the henchman’s pool is equal to the asset’s former value.

Outcomes

First and foremost, winning the roll determines whether or not the agent proceeds towards achieving the objective. If the agent fails, then Control may complicate the current situation or otherwise make things worse. Failure will never be enough to stop the agent, but it might shut off a particular line of inquiry.

The trick, is, of course domination:

Experience Dominates: Reduce Exhaustion by 1, or kill a henchman involved in the scene.

Opposition Dominates: Control adds a die to his asset pool OR kills an asset in the scene.

Support Dominates: One Experience dice is replaced with a support die.

Exhaustion Dominates: Exhaustion increments by one.

Asset Dominates: Asset increases in value by one step.

Endgame

The game is going to end when one pool dominates, or when the Threat is averted. Averting the threat is a function of play, and is a successful outcome, but the unsuccessful outcomes are mechanically dictated.

In the case of a failed outcome, It is entirely possible to pick up play and continue with a new agent stepping into the gap, but if the table agrees, then it might be worth just talking through the impact of failure, and how that shapes the world for future play.

Come In

When an agent’s experience dice are all replaced with support dice the agent’s cover is blown burns out at the end of the current objective (meaning you can burn out and succeed). He needs to be called back into the home office. A long period of retraining is going to follow, and when the agent returns to play, his experience pool will be one smaller. If that would reduce his pool to zero, the agent is permanently retired, either literally or figuratively.

Burn Out

When exhaustion reaches 6 dice, the agent burns out at the end of the current objective (meaning you can burn out and succeed). If the agent manages to reduce exhaustion before the objective is reached, then he can carry on. A burned out agent simply can’t go on – the price is too high.

When an agent with one or two experience dice burns out, the agent will either retire, or come to terms with things. A retired agent is out of play (except perhaps as an asset in later games) but one who comes to terms with things returns to play in a later game with his experience pool one larger.

An agent with three experience who burns out goes rogue, and is removed from play. He may well be a villain or Henchman in future games.