I have been chewing a bit on the mechanization of GM restrictions. Often they take the form of things that the GM cannot do, but such restrictions are usually designed to curb abuses. While that’s admirable, it often has elements of fighting the last war, which feels wasteful.

I have been chewing a bit on the mechanization of GM restrictions. Often they take the form of things that the GM cannot do, but such restrictions are usually designed to curb abuses. While that’s admirable, it often has elements of fighting the last war, which feels wasteful.

But what if you begin from a position of high GM trust? It’s the position I like to take – I am happy to empower any GM who is good enough to know when not to use that power. For that GM, is there a way to impose limitations on their actions which produce fruitful results the same way that some game designs have gotten a lot of energy out of constraining player choice (constraints breeding creativity and all that).

It seems like rich territory, especially because things that might be a bit to “meta” for players might work very well for the GM.[1] If the GM has broad authority but must work towards a particular end (even if it’s as simple as a “this will go well/poorly”) directed by something other than her sensibilities, that could force play in unexpected directions.

The trick, of course, is to make the direction useful. If it’s merely random, then it’s likely to produce random results. The constraint needs to be something that moves play in rewarding directions. This is, on paper, what a GM is often trying to do when “railroading” players, but in that case it is based on the GM’s decision to trust her sensibilities over the organic direction of play.

And that’s the dark specter of this. If the GM is subject to constraints which spill over into play, is it ultimately a different flavor of railroading? I don’t have an easy answer to this, and I don’t know any real way to find out other than testing out ideas.

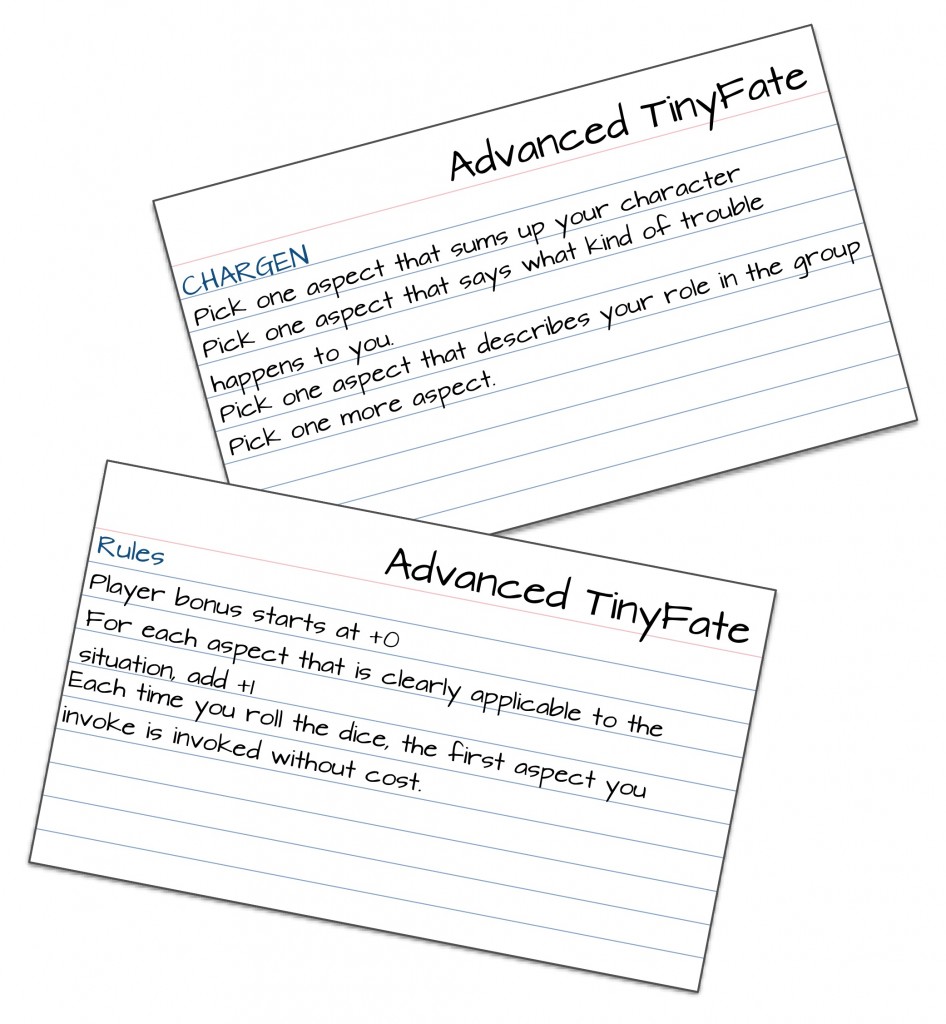

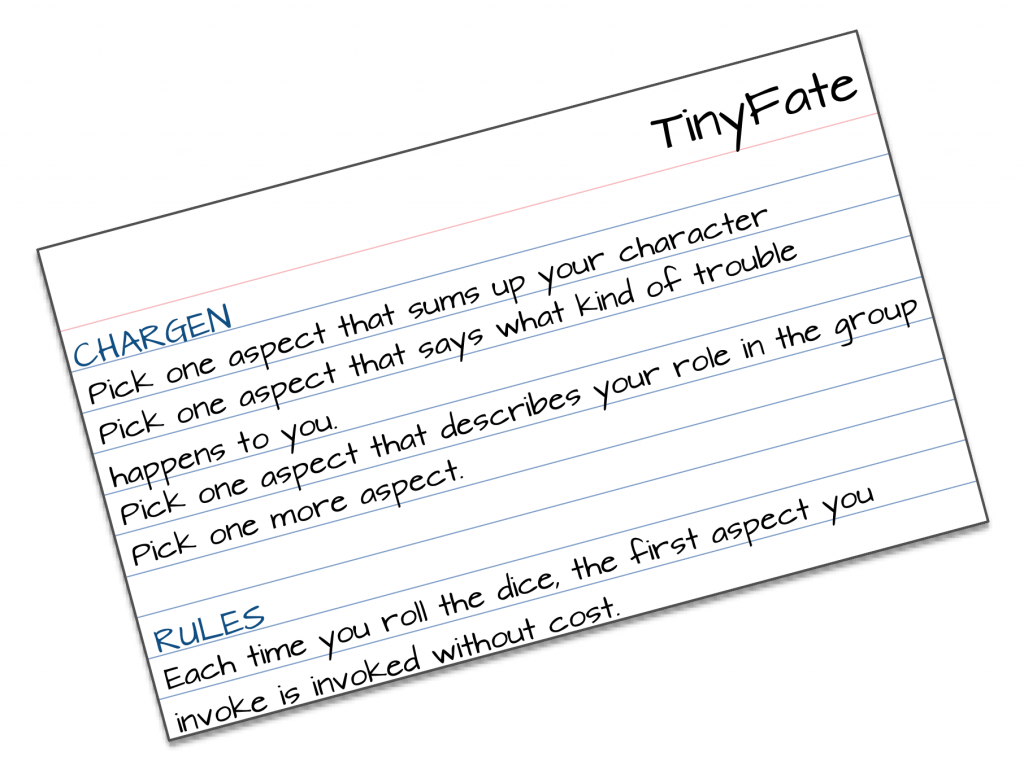

So, here’s one for the curious, using Fate/Fae. It has two modes: hard and soft, and some variants.

The basic mechanic is simple: Make a deck of your player’s aspects.[2] Put it in front of you and flip up the first one.

That is the only aspect you can compel. When you do so, discard it and draw the next card. Now that is the only aspect you can compel.

Now, there are two caveats to this:

First, this will work better if your table allows players to pay each other for compels, even retroactively. I like the bowl of chips in the middle of the table that players can just grab from when they self-compel (or recognize a tablemate doing the same). Yes, that demands high trust, but all this is predicated on an assumption of high trust – if the GM is the only person at the table who can be trusted with authority, your game has deeper problems than someone hoarding fate points.

Second, this does not demand that the GM push hard to compel that aspect, but I would certainly suggest acting as if it does. I think this gets most interesting if the GM treats this as the primary driver of play. Because it’s the character’s aspects, the game will always tack towards the players, but because the “chain of events” is unpredictable, the route may be totally crazy.

A few options and hacks:

- The default treats cards as single use (until you go through the deck), but if you shuffle them back in, then you get the possibility of reincorporation, but lose the guaranteed distribution of hooks.

- This model gets easier to implement if you also use anchors

- This probably should be kept hidden from players, just so they can be surprised, but it may not be required.

- If the GM really wants, she can introduce a number of cards into the deck equal to the number of aspects 1 player has. She cannot dictate when and if they come up.

- Alternately, if the GM wants to use an abbreviated deck to drive toward s a theme, that might be cool.

- If you need more flexibility, flip up the top 3 cards, and you can use any one of them. Replace the card used when that happens.

- If you really want to go nuts, do 3–5 cards, but keep them face up where players can see them. Every time you compel one, replace it, and put one fate point on each remaining one. When the time comes for that one to compel, pay out the full amount on it, rather than the usual 1.