Another super bloated, supplement-inviting Fate hack!

Another super bloated, supplement-inviting Fate hack!

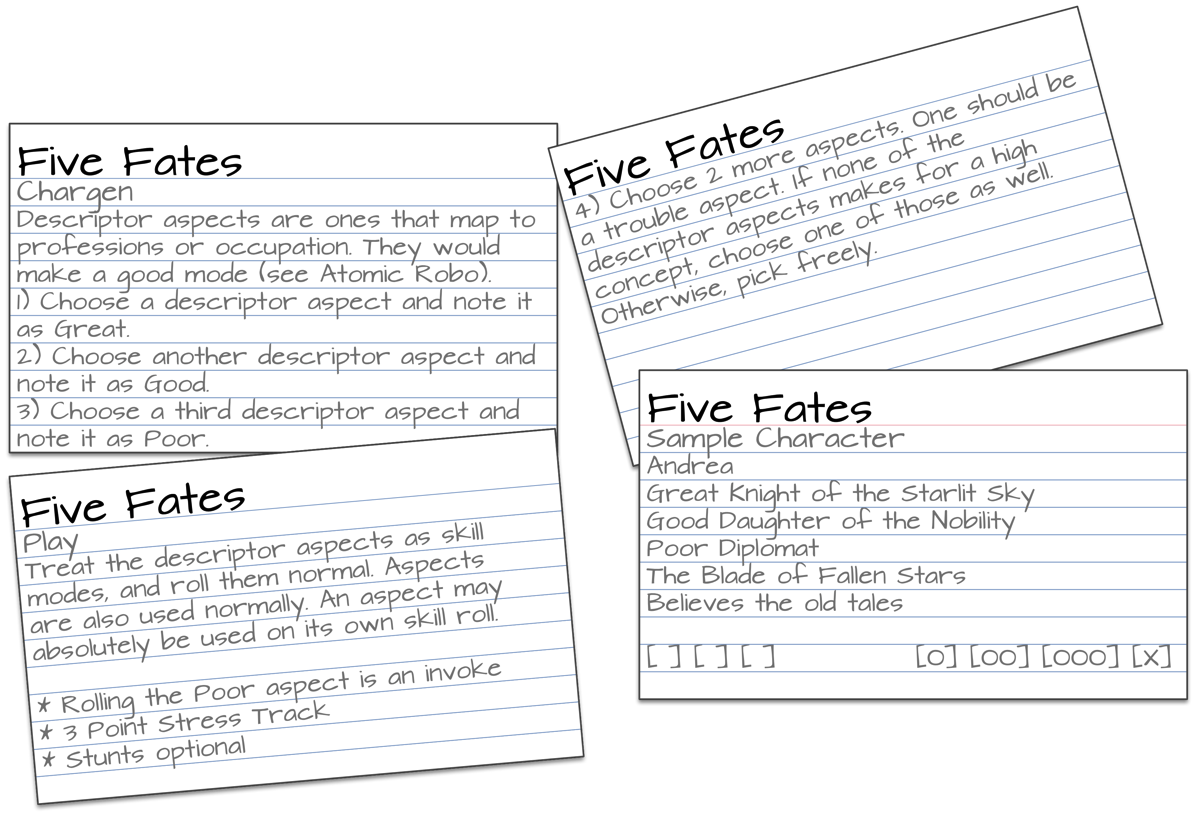

So, I was working on a little side project that won’t be done quite in time for Gencon, and since that was the point of it, I figured I’d share the fruits of it. I was dinking around with fitting Fate event generation on an index card. I started out with simple two die tables, like this set for quick high concept generation – take two dice, roll once on each card, and combine:

Worked ok, but it didn’t seem like the most efficient use of the card. Lots of wasted space. So I tried a different format for some utility tables, inspired by Fiasco:

And that worked ok, so decided to make a set for plot generation, a la two guys with swords:

That, I think, worked pretty well. it’s a fun format, and one I’m going to have to try to get a little bit more use out of.

Any suggestions for tables the world needs?

BONUS

This one is inspired by a question David Goodwin asked. Using it as a chance to try a slightly different dice presentation.

FURTHER EDIT: NOPE. Uneven border doesn’t work. so much for the quick and dirty fix.

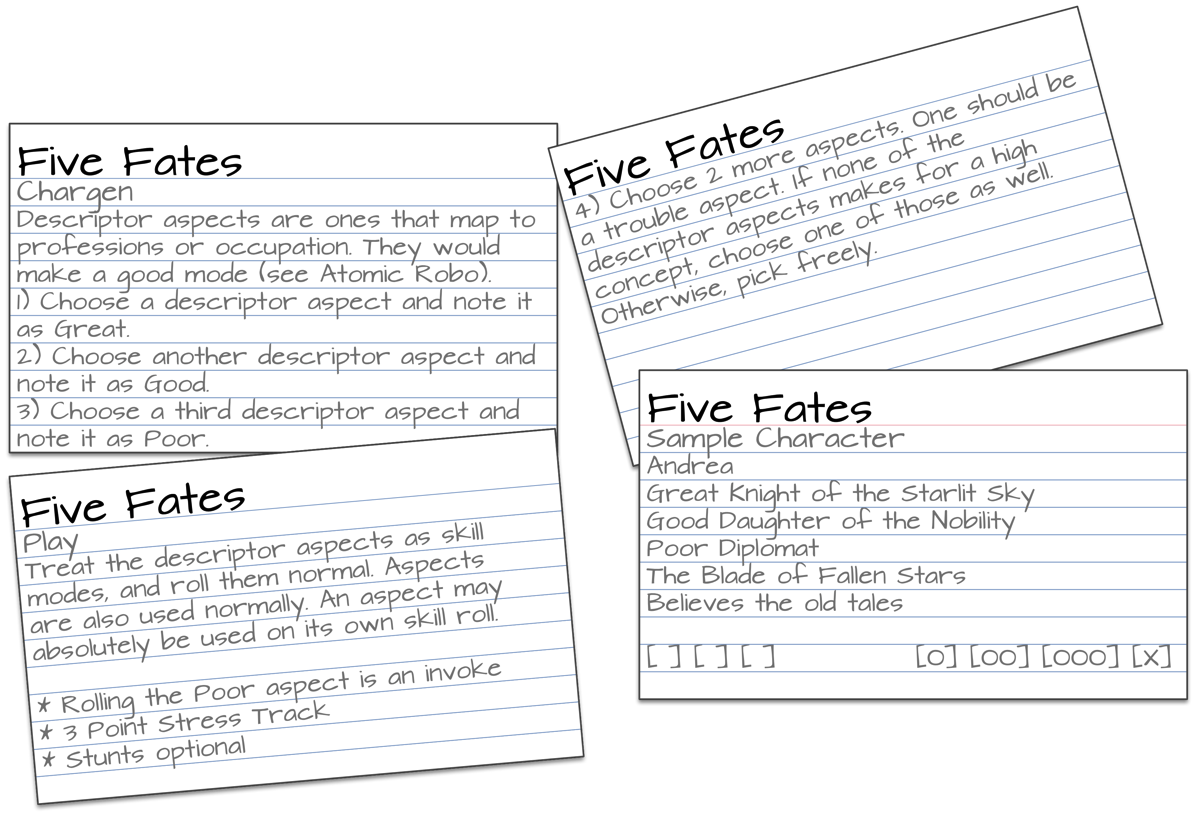

When someone asks if their aspect allows them to do something (or generally tries to act upon ‘aspects are alwasy true’ thinking), the answer is usually obvious, but there are fuzzy border zones, and this create some confusion.

You can resolve that confusion by spending a fate point, but it’s not always clear when that threshold is hit.

Some people think that this should be resolved conservative, with things that *might* be within bounds demanding a FP.

But me, I’ve always opted for a more open policy – the FP is necessary only for stretching the aspect beyond expectations.

In reality, it’s not always clear cut. You and I may disagree on where that line is. And in large part, this is why I feel that as a GM you will rarely go wrong with the more generous interpretation. If the player constrains themself, then you aren’t creating a problem, but if you end up constraining a player, that’s fun-corroding.

On the off chance that you need an example, let’s say I have the Hell on Wheels aspect and two questions come up:

1. Do I know how to hot wire a car?

2. Do I know a car thief in this town?

Is #1 covered by the aspect as written? Mmmmmaybe. By conservative interpretation, the player would need to spend a FP to be able to do it (however that is handled), by a liberal interpretation, it’s in bounds.

Is #2 covered by the aspect as written. Probably not, but since you can make the case that it’s in the same domain, then it becomes possible with a Fate Point under a liberal interpretation (and probably impossible under a conservative one).

This is not to say that my answer is the right one. Both approaches have their place, and there are a lot of nuanced issues of genre, taste and tone that they fold into. But what *is* important is that everyone at the table have the *same* understanding of how aspects are being interpreted.

Last night, a friend of mine was asking about how to handle damage in supers, with the specific question being how you can really have a normal human get knocked around in super-strength context (getting smashed through stuff etc) without totally snapping suspension of disbelief. This lead to a good discussion, but it also generated a very useful tangent – It created a much simpler solution to knockback and property damage for invulnerable characters.

At it’s heart, it boils down to this – when invulnerability cancels out damage, it “grounds out” as property damage. That is, you take a hit for X damage, that damage is reduced to 0 but the action that corresponds with that mechanical even is you getting knocked through a wall or similar.

This is related to Ryan Danks’ great post on how to handle Superman’s Invulnerability but scaled down somewhat for characters who are a bit less truly invulnerable, but are still superhumanly tough. Where Superman sheds damage onto the setting, a less powerful character sheds damage onto the environment.

This is a bit of narrative sleight of hand, but it simplifies one of the great bugbears of supers design – knockback. Conceptually, it’s an essential part of superheroic fighting, but mechanically it has a habit of introducing complexity that is best compared to grappling rules.

Now, the exact implementation of this idea depends on the details of how invulnerability is implemented in a system, and there are lots of ways to do that. It might be ablative, it might be armor, it might be any number of things. For example, let’s say that in fate we treat it like a skill to roll after you get hit, with a difficulty based on damage.

Admittedly, that’s probably not how I’d handle invulnerability, but hopefully it showcases the idea well enough. Obviously, any invulnerability effect needs to have limits, and those limits may tie into how often you can get knocked around, but that is ultimately an implementation detail based on what you want to showcase.

There is a tendency in RPG’s to think of actions as atomic. You swing a sword, pick a lock, climb a rope or whatever. This is, of course, a convenience that helps mechanize the experience. It allows us to create a consistent fiction and crystallize out moments of uncertainty in the form of actions with uncertain outcomes, resolve those uncertainties, and proceed with the fiction.

There is a tendency in RPG’s to think of actions as atomic. You swing a sword, pick a lock, climb a rope or whatever. This is, of course, a convenience that helps mechanize the experience. It allows us to create a consistent fiction and crystallize out moments of uncertainty in the form of actions with uncertain outcomes, resolve those uncertainties, and proceed with the fiction.

It’s good tech, and it dovetails well with the existence of skill lists. Skills are, after all, flags for uncertainty which are agreed upon in advance. As the OSR joke goes, no one fell off a horse in D&D until the riding skill was introduced. Rolls happen when the conceptual space of skills intersect with the crystallization of a challenge.

For all that this approach is very common, it is not the only way to go. Even within atomic systems, things break down when you step back a level of abstraction – picking a lock is a very different challenge than getting past a door, which might also be smashed, circumvented, dismantled or otherwise removed from the equation. In an atomic system, each of these is a separate moment of uncertainty resolved differently. In fact, one of the hallmarks of a good GM is their ability to interpret unexpected actions within this atomic model.

In the case of games without skills, there are no clear intersections. That is, whereas pickpocketing, climbing and lockpicking provide easy cues for when an where to introduce uncertainty and challenge, “The Artful Dodger” does not. And so most game nerds will, effectively turn broader descriptors into what are effectively containers for a skill list which exists in the GM’s head. This is a reason that games like Risus or Over the Edge are often very comfortable to affirmed gearheads – they look light, but they can run on the substantial backend that the GM has in their head.

More interestingly, those sorts of games can take on a whole different character if one is not already trained in more atomic games, but that’s a rare case. But it crystallized very interestingly for me in recent discussion of FAE. See, FAE’s approaches are structurally similar to broad, descriptive skills[1], but they critically differ in that their domains overlap VERY strongly. That is to say, there is no practical way to construct a virtual skill list for each FAE approach because it contains too many skills AND it shares most of those skills with other approaches (sometimes all other approaches).

On its own, this is neither good nor bad, but it creates a very specific problem when one is used to the intersection of skills and challenges. If you are used to thinking of problems in terms of skills, and you present the players with challenges in uncertainty in those terms, then you’re going to be staring down a disconnect, because your players are already thinking at the next level up of abstraction – you may want them to pick the lock, but they want to get past the door.

And this, in turn, points to a very common concerns with FAE’s approaches – that a character will always just pick their best approach. At first blush this seems like a problem because if this were a skill, it would be. Over-broad skills and skill substitution are known problems in RPG design, best avoided or carefully controlled. FAE runs blithely past those concerns, and that looks like a problem.

And it is, if your perspective does not change. If challenges are approached atomically, then approaches get very dull, very quickly – do you quickly pick the lock? Do you carefully pick the lock? Maybe you sneakily pick the lock?

Honest to God, does anyone really care?

If you narrow your focus down to picking the lock, then approaches become virtually meaningless because the action (and by extension, the fiction) becomes muddled. If someone was watching your character pick the door, they’d just see you pick the lock – there would be no particular cues that you were being quick or clever or whatever the hell you were being.[2]

And that’s because picking the lock is solving the wrong problem. There are games where it’s the right problem, and you probably have a lot of experience with those games. It is not the wrong problem in those games, but in FAE, it is driving a screw with a hammer.

The heart of it, to my mind, is this – different approaches should inspire different actions, even if the ends are similar. If there is no obvious difference in how an approach impact the scene, then of course the player will use their highest bonus. This is not them exploiting the system, this is you asking them the wrong question (or going to dice over the wrong thing). You need to step back a level, get the bigger picture, and see what that looks like.[3]

As a FAE GM, you have a little bit less power than normal, but you still have some potent tools, and one of the most subtle and critical is that you determine when a roll is called for. In atomic systems. this does not necessarily call for much consideration – character uses a skill, player rolls the dice, character gets results. FAE does not offer you that same crutch, and if you turn to it out of habit, then you run the risk of diminishing your experience. FAE is a bad skill-based game[4], and if you run it like a skill based game, you may have a bad experience. But FAE is a pretty good approach-based game. Try treating it that way, and see what happens.

I make occasional reference to Anchors as a piece of technology that I use when I run Fate, but I genuinely am uncertain if the idea has ever been articulated fully anywhere, except in bits and pieces.

I make occasional reference to Anchors as a piece of technology that I use when I run Fate, but I genuinely am uncertain if the idea has ever been articulated fully anywhere, except in bits and pieces.

Anchors are a very simple idea, loosely inspired in part by an old idea from Over the Edge where each of the freeform skills of your character had to be reflected in your physical description. It was a very small thing, less notable than the requirement that you draw your character, but it stuck with me because it told a little story about your character. Better, it did it in a way that I nowadays recognize as akin to good brand building. There was no need to tell the story (though perhaps you might) because the richness came from the fact that there was a story.

There is a magic to meaningful things which make them stand out against the backdrop, and this magic is magnified by fiction. It is also magnified by play. I could probably go on about all the reasons why this is so – showing and not telling, microcues, hidden information, symbols and so on, but that would probably be its own post.

Anchors are an attempt to capture that magic.[1]

Practically, anchors are super simple. They are a person, place or thing which you declare to be associated with an aspect. How exactly this is implemented can depend, but the simplest approach is that you create one anchor for every aspect on your character sheet.

For Example, let’s say I have the aspect Always Looking For the Next Big Score. Possible anchors might include:

I pick the one which I want to see come up in play. They might all be true things in the game, especially if I spin the tale for the GM, but the key is that I’ve called out one thing in the game that carries deeper meaning for me. I then do that for each of my aspects.

Anchors represent a concrete way to leverage an aspect, especially an abstract one, into play for both the GM and the player. They provide physical things to hang compels and invokes off of. Aspects can still be used as normal, but the anchor expands that domain in a very specific way.[2]

For players, this is an obvious avenue for some setting authorship[3] but, importantly, not a mandatory one. An anchor can be as small as a piece of personal equipment or as large as a 13th Age Icon.

For a GM, it creates a host of signifiers to stand in for player’s aspects in the setting. This is incredibly handy when you sit down and start thinking about how to make adventures matter to the players – in addition to the conceptual hooks that aspects offer, you now have a host of physical hooks that you can draw into a game that you know have meaning.

Anchors are a great way to get more out of aspects in their most basic implementation, but once you grasp the core idea, the idea can be expanded in a few ways. For example:

There’s more, but let me pull this together into a practical example. Let’s say you want to capture the idea of the 13th Age’s icons in Fate. You tell the players that they need to choose an Anchor for their aspects, and they have the option of picking a second anchor. However, the second anchor must be one of the icons of your game[4]. There might be some limit on how many times a given icon can be used by one character (say, 3) but at the end you have a full spread of icon relationships and, sneakily, a bunch of second-order relationships through the character’s aspects. That is, if your anchors for Master of the Night Wind are “Academe Mystere” and “The Stormcaller” then the GM may very reasonably ask herself “What do the Academe and the Stormcaller have in common?”[5]

This is, I will admit, a very long post for an idea that can be boiled down to “After you choose an aspect, name a person, place or thing which is connected to it”, but I consider this one of those very simple ideas that can go a long way, so I wanted to frame it out properly.

I have a FAE hack (Which I am calling FAE2[1]) that has been eating my brain which I will almost certainly use next time I need to run FAE because it’s very simple to implement, requires minimal changes from any existing material, and it opens a number of doors that I want to see opened.

The hack is this: When you make a roll, rather than choosing an approach and rolling that, you pick two approaches and add them together, and use that. Mechanically, this means that the potential bonus has changed from 0–3 to 1–5, so it will require a small (+2ish) bump to any passive difficulties or simply statted enemies, but otherwise you can largely play as written[2].

So why do such a thing? I have many, many answers:

I fully get that for some people this might be an arbitrary or fiddly change, so I’m absolutely not suggest ing it as a blanket change. But the benefits seem so self-evident to me that there’s no way I can’t try it.

Fred threw me an interesting idea about approaches and alignment yesterday, and as is the nature of such things, I’ve ended up in another place entirely. The other half of the thinking in this came from watching some Anime – Bleach in particular – where you see sometimes-interesting, sometimes-lame narrative tricks that keep fights interesting despite super powerful protagonists. One of the better ones is when the hero’s heart is not in the fight, and so they do poorly against an opponent they could usually squash because they’re hesitant or distracted. The passions that make them strong (compassion, justice, whatever) become weaknesses.

You can model this with aspects, straight up, but I really got in my head the idea of that emotional component of a fight, where what’s really going on (through stakes, escalation and so on) is that the hero’s reasons to fight are steadily being brought online, especially in a climactic battle. It’s a little meta, but storywise, that’s often what’s going on.

This in turn lead to thinking about baselines. If you’re running a game where everyone can kick ass, how do you model the guy who doesn’t? If everyone’s built from zero, then it’s no big deal, he’s just built differently, but if you’re going to assume a baseline of badassness, then he needs something to bring him down a step or two, which suggested the possibility of approaches with negative values.

That (and the discovery of an old character sheet) lead to some thoughts about Exalted’s four Virtues ( Compassion, Temperance, Conviction and Valor) and how they’re potent but double edged, but how that’s more the domain of aspects in Fate, and that lead to a leap which seemed very obvious in retrospect – aspects are approaches, or very nearly so, so why not mash them up further?

That is to say, every aspect is effectively an approach with a +2 (or –2) value, with rules surrounding when and how often you can apply it. And viewed that way, there’s no real reason that the value of 2 needs to be set in stone – we can embrace the idea of variable potency by simply having it be baked right into the aspect – I’m a knight of the cross (3) and a drunk (1) but I’m also a secret freemason (2). Not only do those have different mechanical weights, they enrich the data set. Consider the character I just described, and contrast her with I’m a knight of the cross (1) and a drunk (2) but I’m also a secret freemason (3).[1] Tells a different story with the same elements.

Similarly, for scene aspects, size can tell a story, so there’s a difference between On Fire (1) and On Fire (2).[2]

Plus, this also allows for a trick that solves one of the great communication problems surrounding aspects – I can explicitly write down how I want it played. That is, if I note a number (2) then I’m saying that’s a normal aspect that can hinder or help me. But if I want, I can explicitly note it as positive or negative (+2 or –2) (though I can’t think of many reasons to do the latter) to indicate that it can only be used in that way. That’s important mechanically, but it’s more important as a communication to the GM and the table that makes it clear where I do and do not want my safe zones to be.

Ok, yes, at this point were going far enough from Fate Core that this probably would merit its own build, so I’m going to have to sketch it out some, maybe run a game or two, but I have to say, I’m a little excited by this line of thinking.

Parenthetical numbers also allow for these things to be called out as aspects in plain text without additional formatting, which is handy if you’re going to steal HQ’s 100 word chargen. Which you should. In fact, it’s a great way to do pre-gens, since you could leave the blanks, and let the player come to the table and weight them. ↩

That’s actually the tip of a very big mechanical iceberg. By allowing the improvement or diminishment of aspects, you open the door to a whole new approach to how aspects are mechanically interacted with. Just putting a flag in that for the moment, since that’s totally it’s own subject. ↩

Some great discussion over on Google Plus about yesterday’s post made it pretty clear that the idea has some legs, so I’m going to drill down and talk about it a little bit more.

First, a little more discussion on how these GM approaches are used. When I came up with the list of GM approaches, I did not base them on things that GMs can do (that’s a larger list) but rather, I specifically limited them to consequences, with an eye on how to handle the player losing a roll. Things like harm, loss of resources, misinformation and so on are all non-blocking consequences of things going wrong, and the approaches reflect that.

This is a big difference between these and the GM “moves” of the *World games. Moves are much broader and cover things both in and out of conflicts, while approaches are fairly conflict-centric. It would not be impossible to extend the approaches into a set of move equivalents, but you’d need to expand to include things like introducing a fact, foreshadowing the future and so on. Coming up with that list might take a few minutes – less if one wants to just lift the list from Dungeon World – and the bonuses might not be relevant, but that’s probably a subject for some consideration.

An additional difference is that approaches are primarily reactive rather than proactive. They can be used proactively, in a “guy with a gun kicks in the door” kind of way, but they’re primarily used in response to player actions. After the player determines their action, the GM considers what sort of outcome might be the most interesting and how hard it should be, and picks the approach that lines up with that.

Second, GM approaches need not be the only factor in play when coming up with the net difficulty. They make a good baseline, but scene-specific elements can influence things. Oe easy way to do that is by giving NPC’s stunts and aspects, so that the underlying approaches are the baseline, and the stunts modify those.

Alternately, you could combine GM approaches with NPC approaches. If both are rated from +0 to +3, then you can get a totally difficulty from +0 to +6, which is a pretty robust spread.

Third, the idea of GM character sheets ended up surprisingly toothy. Specifically, the GM stunts were pretty awesome as people started coming up with their own. I hope that some other folks decide to chime in with their own.

A few fun ones:

From Seth Clayton – Cliffhanger – +2 to Escalate at the end of a session.

From Matt Wildman: I Can Think Out Of The Box Too – +2 when I introduce something even the players weren’t thinking of to steer the story in a new/different direction.

Mine: Charming Adversaries – +2 When I use an NPC to misrepresent the PCs as bad guys.

The other day, I talked up using different approaches for NPCs, and while I think that’s a solid idea, it also opens the door on something even more interesting – GM approaches.

Unlike NPC approaches, GM approaches are less about the action and more about GM intention. That is to say, GM approaches are based upon the expected consequences of the GM’s actions. As such, the core GM actions might be:

Harm is reasonably self explanatory, since it comes up in every fight, though anything that might result in PC harm (or certain types of aspects) falls under this.

A successful Misdirect gives the players false information. How you handle that will depend on your table habits regarding secrets, but the result is fairly straightforward.

A successful steal strips a player of a resource. Maybe it’s cash or a weapon, but it might be something more ephemeral, like support or an ally.

A successful Misrepresent changes how the world sees the characters, and comes up in many social exchanges.

A successful delay, well, causes a delay.

A successful escalate makes the situation worse.

Note that one specific approach which could be on that list but is not is stymie – the GM approach focusing on just stopping the players. Why? because that’s the boring outcome. By removing that from the explicit list, the GM is forced to always think about a non-boring outcome.

There’s a lot of room for mechanics in these. They could easily be restricted to explicit outcomes if you want a move-like set of limitations, but I consider that a better starting point than a conclusion. A little more curious is the question of how a GM uses them, and to that end, I see two possibilities.

First, the GM could set these levels at the outset of play (2 +3s, 2 +2s 2+1s) either by her own logic or as determined by players, and then the values are re-allocated whenever you use a +3 – It becomes a +1, bump up a +1 to a +2 and Bump ups a +2 to a +3. Creates a challenge for the GM to balance between outcomes and difficulty, which is kind of appealling.

Second, and possibly more compelling, this allows for the possibility of GM Character Sheets. That is, how would you stat yourself up as a GM? Where do you want to focus your strengths? Heck, throw in some stunts (Because I’m a Killer GM, I get a +2 to harm in the first round of combat) and you could build a whole profile. Write up a few of these and you could have a variety of GM “hats” to choose between before play. Heck, spread them out on the table before a con game and let the players choose the form of the destructor.

Ok, yes, there’s a bit of frivolity in this idea, but as a trick to channel the GM to thinking about outcomes, there’s a lot of utility here.

Also, totally curious what people think their GM sheet looks like.