I’m going to make an assumption at this point that as a GM, you’ve got a pretty solid grasp on success and failure. You understand that failure should not stop play, and that you should only turn to the dice to determine success and failure when both outcomes are interesting and fun to play. So what we’re going to talk about that other stuff that surrounds success and failure – specifically we’re going to talk about risk.

In this context, the risks of a situation are the things that could obviously go wrong, but which do not necessarily make success more or less likely. For example, if a character wants to kick down a door, there is a risk that it will make enough noise alert the guards. This risk has no impact on the action, but it has a profound impact on the situation.

When games take risks into account, they often simply fold them into the difficulty of the roll, and assume success to mean the risks have been addressed, and draw upon the risks in the case of failure. More nuanced games, fold the risks into ideas like partial success or success with consequence, so there’s a middle tier of results between success and failure.

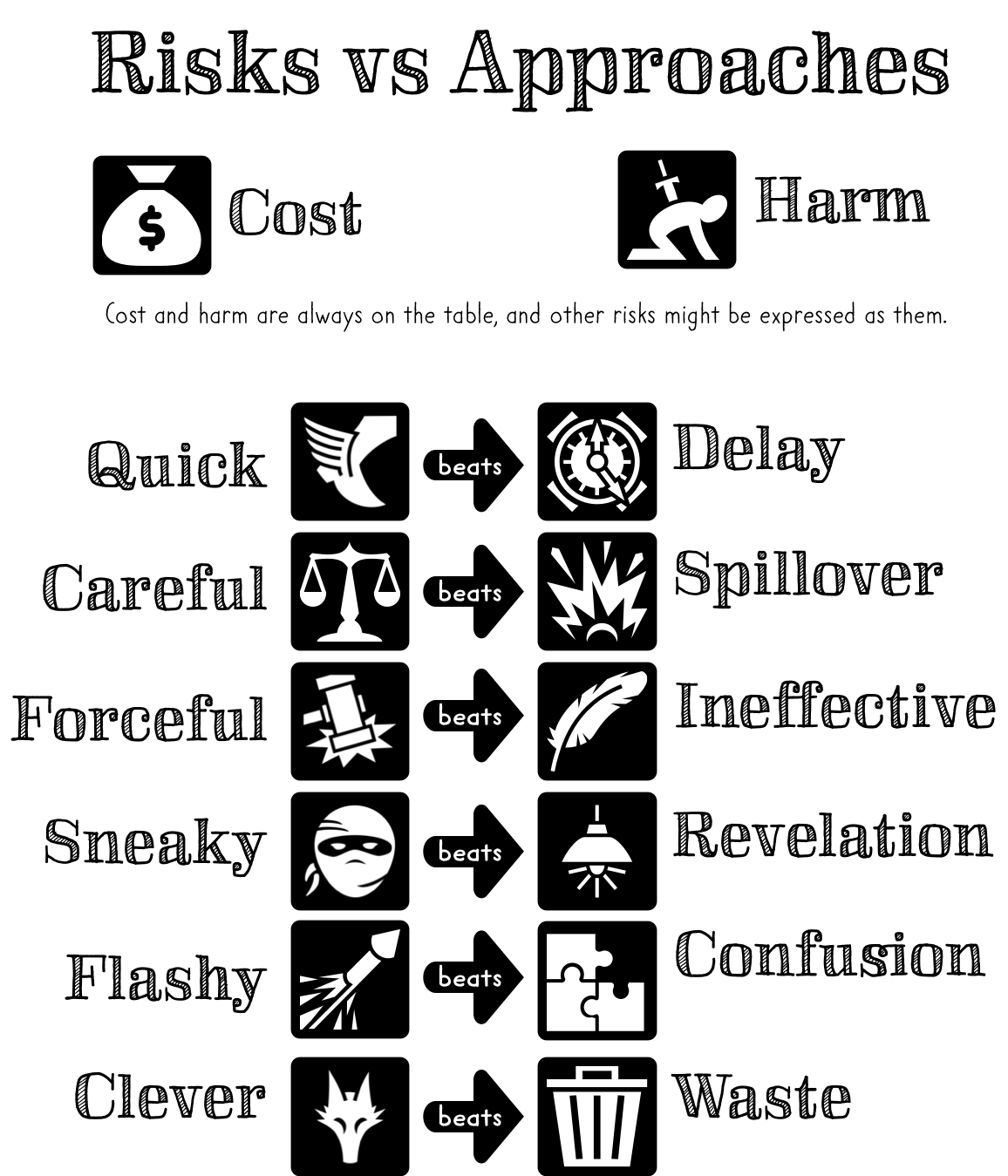

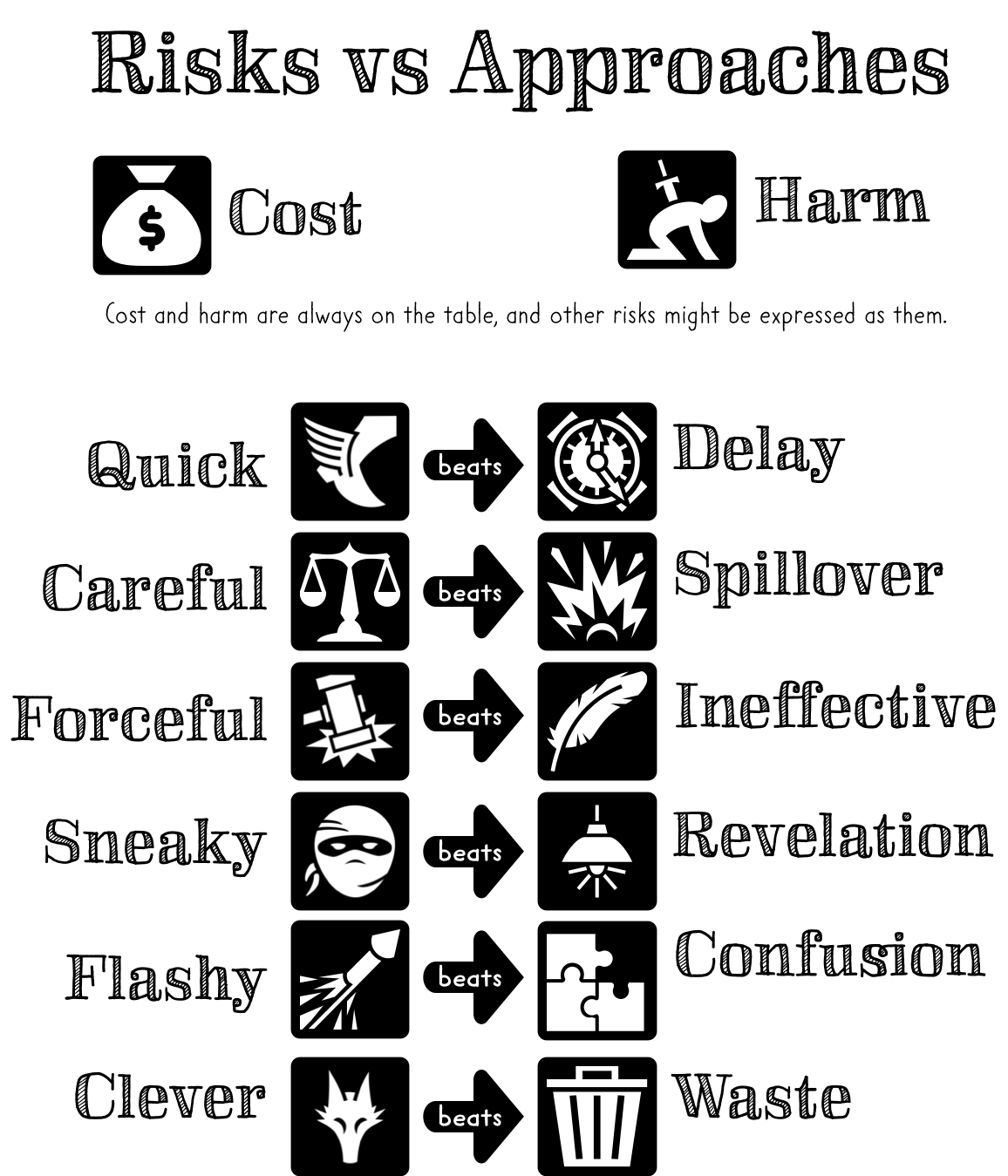

While I can’t pretend to cover the entire range of possible risks in play in one post, I would suggest th

at there are a handful of risk types which you will see over and over again. They are:

Cost: The most straightforward of risks is as simple as a price, usually in the form of lost resources.

Harm: Equally classic, winning but taking an injury is an iconic example of success at a cost.

Revelation: The acting character reveals some piece of information, whether it be a clue or their location.

Confusion: The acting character conveys something other than intended, creating opportunities for upset, bad timing, offense or more dangerous misunderstanding.

Waste: Functionally, this is akin to cost, but where cost is intentionally, waste is the result of misapplication of resources.

Ineffectiveness: Hitting the target may not mean knocking it down. A success without follow through may end up reaping limited (or no) rewards.

Spillover: Alternately, sometimes the problem comes from too much effort – fragile things break, pieces no longer fit, people are annoyed and other results of overkill can all be problems.

Delay: Sometimes things will just take longer than intended.

(This list is almost certainly not comprehensive, and I’m 100% open to suggestions for additions.)

Now, this list is very useful to a GM who is looking at a situation and thinking “ok, what might the risks be here?”. Running down a simple checklist is an easy prompt to the self to consider potential options before the dice hit the table. But, critically, almost no situation will call for all risks. If there’s no one watching, there’s no much risk of a reveal. If there’s no hurry, then delay is not much of a risk. This is not a problem – that different situations have different risks is a feature because risks drive player behavior.

That is to say, risks impact how characters approach a problem, and they provide an avenue of action and play that grows naturally out of the success and failure that are already afoot in your game. Two mechanically identical rolls can feel drastically different when presented with different risk profiles. That benefit is so profound that we’re starting today with laying the groundwork on thinking of risks as something distinct from difficulties.

Risks and Approaches

(This bit is fairly FAE Specific, but some of it can be more broadly re-used).

I love Fate Accellerated, but I think it’s generally understood that there are times when the question of which approach to use becomes more of an exercise in mechanics than fiction, which rather misses the point of using FAE in the first place. I’ve written about a few other ways to approach the problem of how to make it matter which approach someone choose, but I think the real secret sauce lies in risks, with one simple trick of perspective:

Approaches are less about success and failure than they are about mitigating risk.

Ok, maybe that sounds weird, but work with me here. Straight success is not hard to pull off in FAE, even with a ‘weak’ approach. Difficulties aren’t super high, and aspects provide a lot of extra oomph when needed. But for all that, there is still incentive to explain why everything you do it clever and therefor gets your +3 bonus.

But suppose you looked at that list of risks as the inverse of approaches. Remove cost and harm – they’re always on the table as the situation demands it – but the rest line up suspiciously well.

If you are not quick then you risk delay.

If you are not clever, you risk waste

If you are not forceful, you risk ineffectiveness

If you are not flashy, you risk miscommunication

If you are not sneaky, you risk revelation

If you are not careful, you risk overkill

That is to say, the choice of approach can be a reasonable response to risk. In play, this means that the right choice of approach can nullify a risk.

Ok, that’s all well and good in theory, how does that look in play?

So, mechanically, when the GM looks at a situation in play, it should have one or more risks (if there are no risks, then definitely question why there’s a roll at all), and set difficulty, with the reminder that 0 is a totally reasonable difficulty. Then add the following 2 twists: First, every 2 points over the difficulty can cancel out a risk (if it makes sense). This makes for a sort of proxy difficulty increase with automatic success-with-consequence. Second, the approach chosen cancels out any appropriate risk.

To go back to the door example: Finn needs to get through a door to escape pursuit. It’s locked, and the guards are in pursuit, so it’s time to kick it open. It’s not a super robust door, and the GM is comfortable with a difficulty of 1, so she does a quick audit of potential risks:

Cost or Harm aren’t really in play directly, but they’re always on the table when things go pear shaped.

Waste isn’t much of a concern. There are no points for neatness in door kicking.

Delay on the other hand is a problem. If this takes too long, the guards may catch up.

Miscommunication isn’t really a concern, since ideally there’s no audience.

Revelation is borderline – the GM could say that one of the risks is that the guards will know which door Finn went out. However, he’s going to break down a door, so they’ll probably be able to figure it out however the roll goes, so the question is more whether they’ll find him soon enough to matter. From that perspective, this shades into the territory we’re already covering with the risk of delay, so the GM lets this one slide.

Overkill is almost certainly not a problem

Ineffectiveness, on the other hand, really would be. He cannot afford to be dainty here. But despite that, this merits a little thought too – the consequence of ineffectiveness is also that the guards catch up, so is it really that different? Wouldn’t ineffectiveness really map to failure in this case? Those are reasonable concerns, but they also need to be balanced against the sensibilities of the moment and the fact that the GM has already been generous about Revelation, and this feels right. However, double dipping on the guards catching up is unfair, so instead she considers the door not quite breaking all the way and him having to squeeze though, probably leaving some loot behind.

So with that in mind, the GM figures the situation has risks of delay and ineffectiveness one top of the +1 difficulty. If he succeeds, he’ll get out through the door, but there’s a risk that the guards will be in hot pursuit if he takes too long, or he may have to leave some loot behind if he can’t kick the door all the way open.

In terms of pure math, this suggests a fairly large number of options:

If Finn tries to be quick (nullifying delay):

- On less than 1, he fails, and has some guards to fight

- 1-2: He manages to squeeze out the door but leaves some loot behind.

- 3+: He kicks the door open dramatically and runs out onto the street.

If Finn tries to be forceful (nullifying ineffective):

- On less than 1, he fails, and has some guards to fight

- 1-2: He kicks the door open, but the guards catch up and the chase continues out onto the street.

- 3+: He kicks the door open dramatically and runs out onto the street.

If Finn tries some other approach.

- On less than 1, he fails, and has some guards to fight

- 1-2: He squeezes through the door, dropping loot, and it pursued by the guards.

- 3-4: The GM makes a quick judgement call based on which next step seems more fun, or if Finn’s description suggests a particular direction, and Finn either drops some loot, or is pursued.

- 5+: He kicks the door open dramatically and runs out onto the street.

That looks complicated, but in practice, it’s pretty simple and logical. And critically, it makes the choice of approach meaningful. This is a situation where a Quick or Forceful character will have an opportunity to shine, but success is still equally within reach of all characters.

And, critically, there is still plenty of room for creativity and problem solving. If a player has a clever way to mitigate or transform a risk, or use an approach in an unexpected way, then awesome! That’s a good thing! The goal here is not to penalize “wrong” choices, but rather to give weight to the choices made.

Risks and Success

But wait, you might say: What if avoiding a risk is implicit in the action the character wants to take? What if I want to sprint, or sneak or do something else where triggering the risk would equate to failure?

The answer, counterintuitively, is that it changes nothing, except that it clearly communicates the approach that you want to use in this situation, and in doing so, may call into question the necessity of the roll.

That is, if there is only one risk (say, getting spotted or not), then that risk is obviated by using a Sneaky approach, at which point, why are you rolling? The answer might be “more or less because rolling is fun” in which case I refer you to the next section, but ideally it’s because “Oh, right, there should be more going on for this roll than this simple binary – what other risks might be in play?”

All Risk, All The Time

Ok, dirty truth. I have occasionally found myself in situations where I’ve called for a roll and I’m not really prepared for failure. I should know better, but sometimes the situations just feels like a roll is the right call at the moment, and I might need to fake my way out.

Risks are a great tool in this situation because, frankly, I can drop a 0 difficulty and assume success, with the question being one of risk. See, these situations almost always have multiple risk vectors in play simultaneously, and that is what the instinct to roll is responding too. I’m not really looking for success or failure, I’m just looking for how well things stay under control. “Failure” in this situation means all the consequences come home to roost, even the one the approach was supposed to mitigate.

Communicating Risks

There might be a temptation to list off risks as bullet points so players can respond to them, but I would recommend against it. The categories of risk we’ve listed are a shorthand, not an actual description – they are for your convenience as a GM, as a placeholder for the actual fictional risks you will describe (or not describe in some cases) to your players.

As a general best practice, use risks as cues for describing the situation. You don’t need to elaborate on each risk, but when you think of descriptive elements for the scene, take a moment to think about each risk and see if it might contribute to the description.

If you do start literally laying out risks as Mechanical constructs, I’ll be curious how that goes for you, though.

Risks vs. Consequences

This is a bit of bonus content. If a risk is something that might happen, a consequence is something that will happen as a result of action. Beyond that, they are structurally very similar, and once you have gotten the hang of thinking about risks, you can apply the same sort of thinking to consequences to use one of the most powerful tools of scenario design out there.

That is, if you want a really solid session, one trick for doing it is to present a single, simple problem or task which the players can absolutely accomplish, but which has numerous dire consequences. The adventure then becomes a matter of identifying the consequences and figuring out how to nullify or redirect them before performing the main task.

Which is to say: It’s how to design a heist.

Icons used are largely from game-icons.net

I just tweeted about this, but I like this enough that i want to capture it here. I have finally gotten around to reading the new Over the Edge. It’s not released yet, but I backed the kickstarter, and the pretty-much-final preview version got sent around recently, and I finally sat down to read it. I had not read any of the previews before that for two reasons. First, OtE is an INCREDIBLY important game to me, so I was willing to be patient. Second, I hate reading multiple versions of a game because all the rules stick in my head, and I end up in a muddle when all is done. This is why I don’t read any of the preview editions of even games that I love and am super excited about, like all of the Blades in the Dark family of stuff.

I just tweeted about this, but I like this enough that i want to capture it here. I have finally gotten around to reading the new Over the Edge. It’s not released yet, but I backed the kickstarter, and the pretty-much-final preview version got sent around recently, and I finally sat down to read it. I had not read any of the previews before that for two reasons. First, OtE is an INCREDIBLY important game to me, so I was willing to be patient. Second, I hate reading multiple versions of a game because all the rules stick in my head, and I end up in a muddle when all is done. This is why I don’t read any of the preview editions of even games that I love and am super excited about, like all of the Blades in the Dark family of stuff.