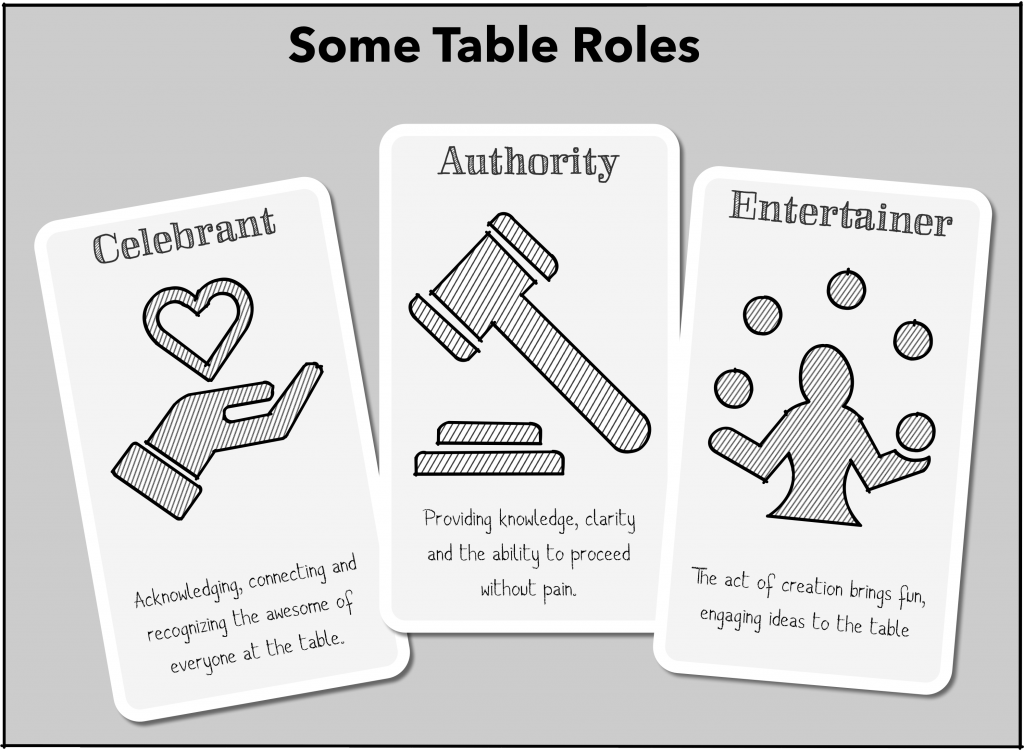

These are not all the roles, just the 3 that I think the GM or system need to pick up. They aren’t exclusive to GMs of course, and there are other roles, but that’s probably another post.

After yesterday’s post about GM Roles, I had a fun discussion on G+ which proposed a model – given any set of GM roles (not just the bog three that I talk about – Authority, Entertainer & Celebrant) you can ask if a game Provides, Supports, Expects, or Ignores that role.

If a game provides that role, then the game is designed to do the heavy lifting for that particular sort of work. A very clear and strictly procedural game might provide authority. A game with a lot of pre-generated content might provide entertainment. A game with rituals and procedures for cross-engagement might provide celebration.

This is usually not absolute. Computer games & RPGs need to fully provide these things, but in tabletop the players still have a role to play. The GM still needs to do something for each role, but the game actively minimizes it.

A game that supports a role provides tools to help with the role, but those tools expect a higher level of GM engagement. Any game with clear and comprehensive rules is supporting authority. A game that provides prompts and seeds is supporting entertainment. A game that has cross-table hooks is supporting celebration.

A game that ignores a role might provide incidental support for a role, but it’s not part of the design or intent. This can be an oversight, but often it’s because the game has specific goals. A very freeform game may ignore authority. A small rules engine may ignore entertainment. A lot of older games ignore celebration.

Obviously, it is something of a spectrum between providing, supporting and ignoring. There’s no precise metric to determine if a game strongly supports or weakly provides a role. That’s fine – the utility of the model mostly relative anyway.

More tricky is the nuance of the difference between ignores and expects.

When a game expects a role, it may look a lot like it ignores it, but where ignoring a role happens because the designer doesn’t consider it important, expecting a role happened because the designer thinks it’s critical, and that it’s what the people at the table are bringing to the game. A game that expects a role might still have a few rules to support that, but only a few – enough to nudge things. Rules that nudge rather than push.

That is, a game might have very loose and simple rules because it expects authority to provide clarity and interpretation in flight. A game might provide little in the way of content or inspiration because it expects entertainment to flow from the table. A game might provide little in the way of celebration because it expects that people are already going to play in a cooperative and supportive fashion.

As such, expectations contain a contradiction (one related to the “fruitful void”, of old) – their lack of tools is a reflection that they may be the *most important* thing in the designers mind. They will also speak to the strengths and weaknesses of any given game.

I find this an interesting lens to turn to my game shelf. It quickly becomes apparent that different games have prioritized differently. If there’s an example of a game that Provides all three roles, I haven’t found it. A more common pattern is that a game provides one, supports another and expects a third.

For example, in my mind, Fate provides celebration, supports authority and expects entertainment. The whole aspect system is in place to make engaging with the content of people’s sheets a critical part of play – playing Fate without celebration requires ignoring a lot of the game. It’s lighter on authority, partly because there’s room for interpretation, partly because it’s a semi-generic engine that expects there may be some assembly required. For entertainment, Fate largely stands back and expects the table to step up – the game is about YOUR characters and what you bring to the table.

This makes it a great game for people with authorial instincts but no desire to play games that feel like writing exercises (*cough*Me*cough) but it also highlights some of the weaknessesof Fate. Expecting entertainment is very demanding, and can introduce blank page problems. For a lot of players, Fate is a better game when it also supports entertainment (with setting material, prompts, sample aspects and so on), and tellingly that is the direction a lot of people have taken things.

Let’s compare that to Fiasco – I would say Fiasco supports authority, provides entertainment, and expects celebration. Some of these are muddy – its authority support is on the strong side, and it has a few rules that might push celebration up to “support”, but I’m of with this general take on it. Playset provide strong, driving prompts for entertainment, and there are enough rules to keep things moving, but lots of space for non-rules on the authority front. Celebration is largely on the players, and is going to make or break the game. This might seem like a gap, but phrased slightly differently, this is saying that the table is going to have as much fun as it wants to have.

On the other hand, there is a common Powered By The Apocalypse mode which provides authority, supports entertainment and expects celebration. The rules are designed to strongly hold authority, but also provide prompts and suggestions as well as tools for structuring the entertainment portion of things, but celebration is expected to emerge from play. Different PBTA games have tweaked this formula in different ways, so it’s far from cast in stone.

D&D is even more interesting to look at this way, because there have been enough D&D versions and derivations that you can see wildly different priorities between versions. D&D that provides entertainment, expects authority and ignores celebration is a model that’s easy to recognize, but also interesting to contrast with 5e (which I would say takes the curious but appropriately middle-of-the-road position of supporting all three, but expecting or providing none).

Ok, so this is a fun toy. Categorization systems always are. But is it of any real use?

For me, at least a little. The problem that is underlying all of this is my desire for a Santorini experience, and this model has emerged as I’ve looked for patterns to help with that. I think explicitly examining what roles a game brings ot the table is going to make it a lot easier to intentionally design to cover for gaps. So this is definitely going into my toolkit, and we’ll see what kind of nails it hammers.

I Was in the position of entertaining a tween the other day, so I busted out Santorini. If you’re unfamiliar with it, Santorini is a delightful boardgame of tower building and Greek gods. It’s a favorite around our household.

I Was in the position of entertaining a tween the other day, so I busted out Santorini. If you’re unfamiliar with it, Santorini is a delightful boardgame of tower building and Greek gods. It’s a favorite around our household.