Apologies for the repost. I originally posted this right after the game, but then we lost it in the server migration. I meant to repost immediately, but then I started actually writing up the rules for this and was going to release both, but those are taking a bit longer than planned, so rather than keep waiting, I’m just reposting this now and will get to the rest of it later.

Needed to run a game for an interesting mix of folks today, and for a variety of reasons I decided to dust off some Amber-derived ideas I’ve had and take them for a spin. Final result was, while not flawless, REALLY interesting, and I certainly had fun. It was also deeply arts & crafts heavy, so it might be of interest to some.

So, we started from a blank slate at the table, and I introduced Proteus. Proteus is, as the name suggests, a shapeshifter, and they are very old and very powerful. They have a tower at the center of several cities in several worlds, and this is their place of power. Proteus also has a number of children, each of which is a power in their own right. They are…

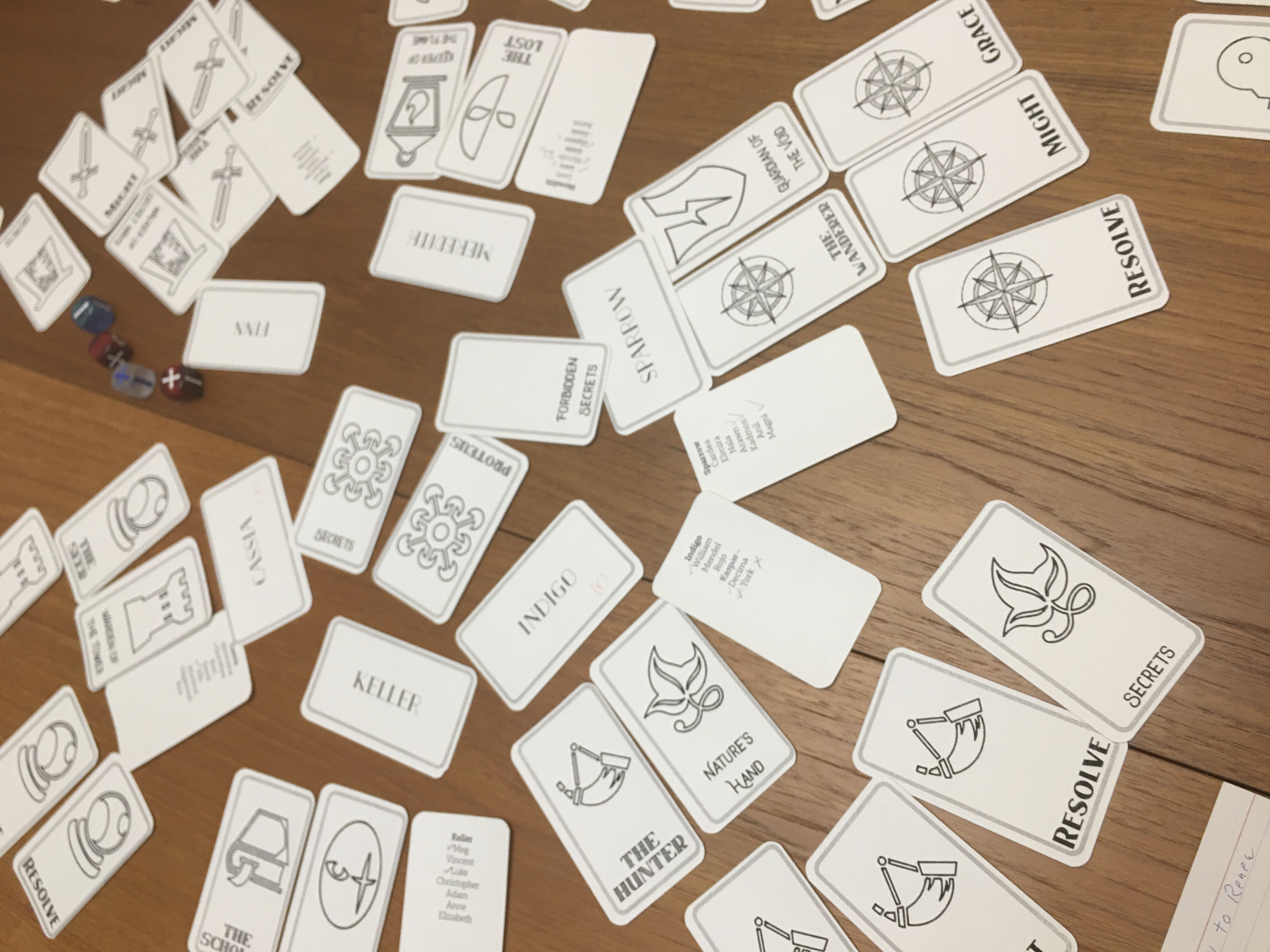

So, at this point I had 7 cards with names on them (Meredith, Finn, Indigo, Keller, Sparrow, Cassia, and Bowie), and I dealt out the top 6 in a circle, setting aside the 7th.

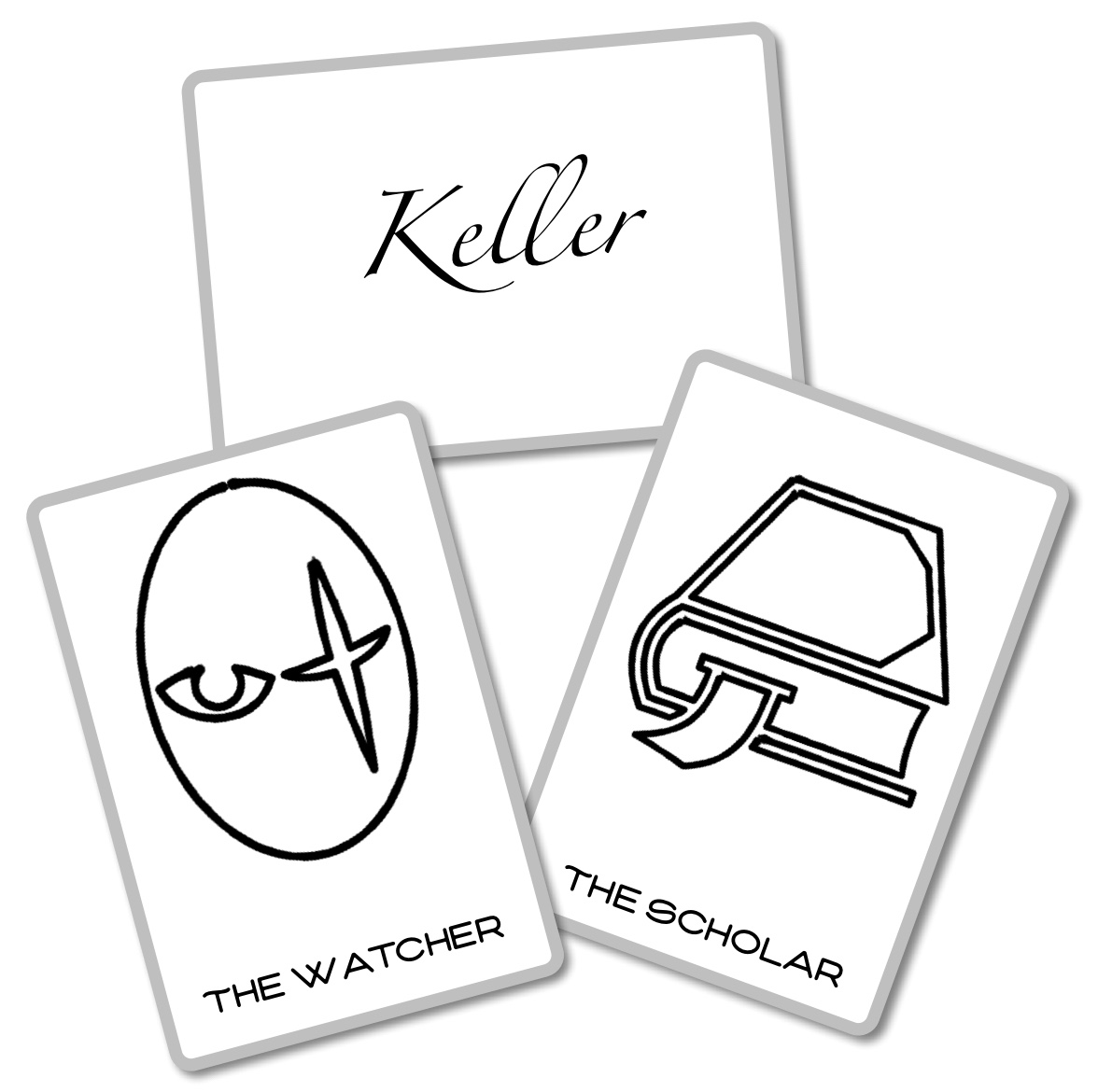

For the next prompt, I pulled out another 7 card deck and said “Let’s flesh them out a bit” and I handed the player to my left a card. Now, this deck was 7 archetypes (The Prince, The Warrior, The Lost, The Wanderer, The Scholar, The Seer, & The Hunter) and I asked players to associate each one with a name, and again I set aside the 7th card.

We repeated this with the next deck of 7 “domains” (more or less arenas of power or similar) – Warden of the Tower, Keeper of the Flame, The Watcher, Nature’s Hand, The Shaper, Walker of Secret Ways, Guardian of the Void, once again letting players assign them. This is where it started getting interesting, since there was some interest in pairings making sense or seeming at odds. When we were done, we had:

- Finn, The Warrior and Walker of Secret Ways

- Meredith, The Lost and Keeper of the Flame

- Sparrow, the Wanderer and Guardian of the Void

- Indigo, the Hunter and Nature’s Hand

- Keller, The Scholar and Watcher

- Cassia, The Seer and Warden of the Tower

(And I had privately set aside Bowie, The Prince and Shaper as a potential future NPC)

So, this was a solid start. I had icons associated with the roles and domains, and at this point we had the skeleton of a setting, so I unpacked a little bit more, and explained that these characters we had just created were the parents of the characters we would play. These characters would be slightly superhuman, heel quickly and be able to travel through dimensions due to the blood of Proteus. They had also been favored by Proteus sufficiently to have lodgings in the tower, which effectively has many floors of well staffed hotel rooms (Proteus has odd ideas about family). As we discussed this, I threw out questions about setting elements, like the cities surrounding the tower, as well as interesting things to be found in the tower. Unsurprisingly, the player contributions did great things to flesh out the setting.

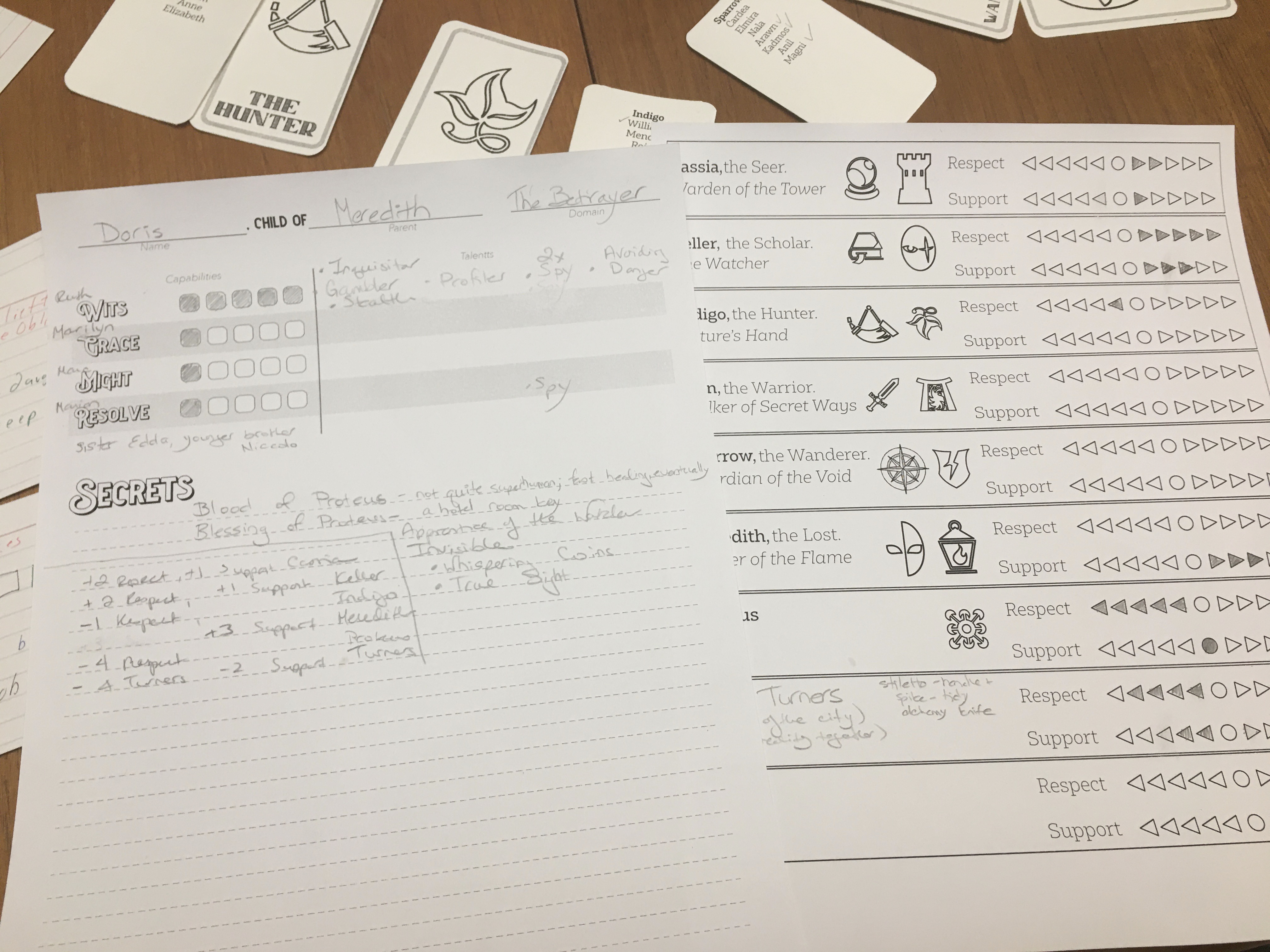

So, at this point we had enough foundation to start diving into actually making characters, so we started with parents and names. I had a list of names for each of the elders, and when players picked a parent, they were urged to pick a name from the list. They had the option not to (representing their name coming from their other parent or some other source) but no one took that option, so we ended up with:

- Lucas, son of Finn

- Kaspar, son of Indigo

- Doris, daughter of Meredith

- Edda, daughter of Meredith

With another quick round of dice, we used some of the other names to come up with NPC siblings, alive and dead. And now the real show began.

So, for a bit of context, I was using a simple four stat system (Might, Wits, Grace & Resolve), so for each elder I put out 5 cards – one labeled by the secret of their domain and four of them had the name of a stat on them. The stats were not evenly distributed – Finn, the Warrior has three Mights and one Resolve, for example, while Keller, the Scholar, had two Wits, one Grace and one Resolve. I’d set these distributions up in advance based on the roles, and because one role was missing, the distribution was slightly asymmetric. I also added two extra cards, once for Proteus themself and one labeled “Forbidden Secrets”.

I also gave each player a sheet with the list of elders and a few blank spots, and two tracks for the relationship, one which measured support, one which measured respect.

The mechanical part of this was very straightforward – the players went around picking up these cards. If they picked up a stat card, they got a point in that stat. If they picked up a secret, they got some sort of power, trick or item. In each case their relationship with whichever elder’s card it was, and they got a “talent”, which was effectively a skill keyword.

Where the rubber hit the road was that when a card was pulled, that was a prompt for a question (often a series of questions) about that elder, the character and what the story was behind this. When possible (especially with secrets), the player was offered a choice – ideally one which was pointed at other players at the table. Exactly how this played out could impact how the elder relationships would shake out, and it would be used to select the talent for that round.

Secret cards were put back after they were used (Largely because I hadn’t printed multiples), but the stats got used up as we went. This had a very fun effect of forcing players to develop relationships with Elders they normally would not have picked, and since the Elders had gotten steadily fleshed out as we went, these choices felt toothy.

For example, Kaspar’s first draw was to learn Indigo’s secret (Hand of Nature). I asked how old Kaspar was when Indigo took him on his first hunt, and Kaspar’s player’s answer was “Three!”. I couldn’t pass up that opportunity, so as it turns out Kaspar spent ages 3-5 as a hound in Indigo’s pack. Next round, he picked up one of Indigo’s Resolve card, and the story was even less kind. While Kaspar’s player was enjoying it, everyone else at the table pretty much concluded that they did not want to learn anything from Indigo if they could avoid it.

The other two cards were a bit wild cards. The Proteus card called for a die roll which would provide a random boon, though the character also got to spend time doing something useful for Proteus. Only one character went that route and ended up getting turned into a knife and being used to sacrifice a unicorn, so there’s that.

The Forbidden Secrets deck had a set of cards for other powers and groups in the multiverse, and drawing that meant that I drew one of those and offered them something delicious but terrible. One player immediately drew that, got a fun item out of it, and then discovered she was in a horrible position as a result, and was gun shy after that. However, the deck still showed up occasionally when I needed inspiration for an outside force. A few of the factions on that deck ended up getting added to the blank spots in the relationship sheets, usually as enemies.

So, there were 8 rounds of this, and it was pretty marvelous. As often happens in this sort of thing, players ended up with characters that were not quite what they expected them to be at the outset, but in ways the players really ended up enjoying. The downside of this is that we spent long enough on charges that we did not actually get to start play. However, the players are conspiring to play on Discord or similar, so I take it as a good sign.

All in all, definitely a good experiment. A few takeaways:

- 8 rounds was probably too many. Went a bit slow.

- About halfway through I switched from players drawing one at a time to everyone drawing at once, then doing resolution. It sped things up and made it easier to thread these things together.

- I had intended to pre-load the questions to the draws, but ran out of time, so I was improvising them. Worked out ok, but prepared questions would have sped things up.

- The relationship sliders were really satisfying, but I think I should have leaned on them a little more. Most of the changes were positive, which doesn’t quite align with the tone I imagine – should have had a little more tension in that space.

- I ended up improvising some of the interactions between the secrets. As designed, they were effectively three tier powers, but I hadn’t really considered how they might synergize.

- The deck of threats was a last minute addition, but may have been my single favorite deck. Partly because it was the wildest, but also because what drove me to create it was remembering that putting a bunch of demigods in the middle of reality is only interesting if you can give them something to push against.

- I did not have enough explicit lateral connection and questioning. Added plenty will well-made questions, but if I add another deck, it will be for player to player relations.

So, successful test. The Proteus setting is one I’m absolutely going to use again – it’s my current personal Amber alternative. This particular variation on card-driven chargen – probably the most complicated I’ve tried so far – still holds up.