A while back I wrote some stuff for WOTC, much of which did not see the light of day. No harm in that, but among it had been a couple of skill challenges I was pretty happy with (though, of course, I can find warts in retrospect). James Wyatt was cool enough to say it was all right for me to repost them to my blog, so I wanted to roll out a few with some comments and thoughts.

This one was one of the two really ambitious ones which, I think, really pushes the boundaries of what a skill challenge can do. Structurally, it’s designed to be big enough that it could constitute an entire session if the DM is inclined to play a scene for each action taken – that’s certainly how I envision it being played – but it can just as easily be pushed through at speed moving on to the rest of the adventure.

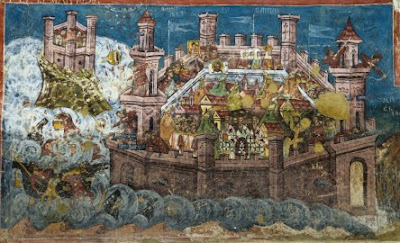

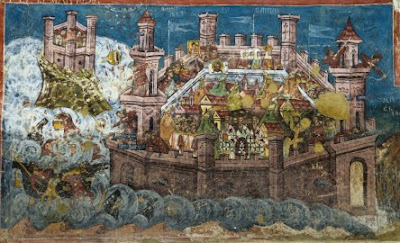

The Siege of Fallcrest

The barking laughter of the gnolls diminished to a low mutter as their leader stepped to the front. Fully a head taller than the soldiers around him, his mane and muzzle were snow white, and his beastial face marked by a cruel scar. In a painful approximation of common he shouted a challenge to the stone walls, and was drowned out by a hundred howls rising behind him.

The arrows from the walls fell short of their mark, but Fallcrest’s answer to the invader was clear. There would be no surrender this day.

This is an intensely detailed skill challenge, of the sort that the challenge itself may be a large part of the session. Not every skill challenge needs to be as detailed as this, but this is a great illustration of just how much you can do with a skill challenge.

This is a good challenge for players who are about to transition from the heroic to the paragon tier, and are ready to move on from Fallcrest (see The Town of Fallcrest in the Dungeon Master’s Guide) to a larger or more exotic base of operations. Mechanically, this challenge changes drastically with each failure. The first failure allows the gnolls to enter the city, the second presses them further in and so on. This is offset by the trigger conditions (below) which only allow one failure to accumulate per day (which is to say, per pass around the table). Any additional failures on a single round trigger the “Casualties of War” event rather than counting as a failure.

Setup: A force of gnolls is marching out of the moonhills, several-hundred strong, intent on raiding Fallcrest. The town has been warned (hopefully by the PCs) and Lord Markelhay is mustering what troops he can, calling up conscripts and sending riders for reinforcements, but there’s no way to tell if they’ll make it in time. Fallcrest’s walls have been proof against attacks in the past, but her garrison is small and composed of more farmers than soldiers, and without the character’s there’s little chance of success.

Character’s try to hold the walls of Fallcrest against the raiders, and try to catch the gnoll’s leader in battle.

Each round of this skill challenge represents one day of the battle, with each character performing an action for the day. Reinforcements are five days out, so odds are good this will be resolved before they arrive. Players may opt to pass on their turn, but any day that a player passes on counts as a failure. Any healing surges lost over the course of this challenge are not recovered until the character takes a long rest after the end of the challenge.

Level: Equal to the level for the party (usually high heroic tier)

Complexity: 3 ( requires 8 successes before 3 failures).

Primary Skills: Dungeoneering, Diplomacy, Heal

Arcana (Hard DC): Moonstone keep has ancient defenses, pillars of moonlight that have long since fallen inactive. If they can be fixed, it will grant the defenders a great benefit. Failing this roll does not count as a failure towards the skill challenge, and a success does not help the skill challenge. Instead, if the player succeeds, then all rolls made after the second failure receive a +2 bonus.

Athletics (Hard DC, one use): The cliff that separates the upper and lower city slows the progress of the enemy forces. After the second failure but before the third one, a daring group might be able to climb up the cliff (a high DC athletics check) in an unexpected location and strike at the gnolls from behind, forcing them to regroup at the top of the cliff. If this roll fails, the forces committed to this would have been better used at the keep, and it counts as another failure. If successful, rather than count as a success, the gnolls are pushed back and it cancels the second failure, returning the challenge to having only one failure.

Bluff (Moderate DCs): The gnolls are fierce and driven, but they’re not terribly well organized, and it’s entirely possible to try to disrupt them with trickery. Manning towers with empty suits of armor to look like there are more men, blowing horns to suggest that reinforcements are coming and other such tricks all stand a decent chance of disrupting the enemy attack. However, there are limits on how far such trickery can go, and each time bluff is successfully used in this fashion, the DC increases by 5.

Diplomacy (Moderate DCs): The people of the city are scared, and will benefit from strong leadership. Giving speeches and talking to people about victory is a great way to do this. Unfortunately, this is harder to do when you’re actively losing, so the DC goes up by five with each failure.

You can attempt to parlay with the gnolls before the first failure, but the best that will do is buy some time. It is a high DC roll, and a failure will result in the loss of a healing surge in addition to the normal results of the failure.

Dungeoneering (Moderate DCs): Before the first failure and after the second one, dungeoneering can be used to help reinforce the walls and gates (of the city and moonstone keep respectively) and operate the very outdated siege equipment.

After the first failure (but before the second one) then you can set traps in the city. These rolls do not count towards or against the challenge : instead on a success it grants another character a +2, and on a failure, it costs the character one healing surge.

Heal (Variable DC): You may use your healing skill to tend to the sick and wounded, helping keep soldiers in fighting trim. Before there are any failures, this is an easy check. After the first failure it becomes a moderate check, and after the second it is is hard.

Alternately, you can spend time tending to wounded allies. This is a moderate DC check, but if successful, another character can recover two healing surges, with no penalties to a failure.

Insight (Moderate or Easy DC, special): You can spend some time watching the gnolls and get a grasp of how they works. While they are brutal and enthusiastic, they are given to infighting, and most of their organization really comes down to bigger gnolls barking at smaller ones, with Whitemane as the biggest one of them all. It’s clear that if Whitemane were removed from the equation, the army would fall apart.

Once you have made a successful insight check, you may still use insight as a lookout skill (see below).

Intimidate (triggered, High DC, usable only once): Immediately after a failure, the next character to act can attempt to cancel the failure by standing and holding the gap long enough for defenses to get by. This is an intimidation skill check (since the trick is getting them to engage him, not just go around) with a high DC. If successful, the failure is cancelled as if it hadn’t happened (though the players do not accrue a success). If he fails, another failure is accrued. Whatever the outcome, the player loses half his starting number of healing surges (if he doesn’t have enough surges, he drops to 1 hit point).

Nature (Moderate DC): Before the first failure, you can skirmish and scout the enemy forces outside of the wall.

Religion (Variable DC, One Use): One time during the battle, you may rally the faithful, delivering a powerful sermon to inspire the troops and reassure the civilians. There are no atheists in the foxholes, and the difficulty reduces as the battle gets worse. Before the first failure, this is a hard DC check, after the first failure it is a moderate DC check and after the second failure, it’s and easy DC check.

Stealth (Variable DC): Striking from ambush is a powerful tactic, but the Gnolls will grow canny to it. The first time you use this skill, it is a moderate DC check, but the difficulty increases by five on each subsequent check.

Alternately, you may use your stealth to spy on the enemy, using stealth for lookout purposes (see below).

Streetwise (Moderate DC): After the first failure, when fighting is in the streets, you can use your superior knowledge of the terrain to scatter the enemy, launch ambushes and generally engage in brutal street-to-street fighting.

Thievery (Moderate DC): War provides opportunity, and it is not hard to do a little looting of your own when you should be fighting. If successful, the success does not count towards the skill challenge. Instead, you find loot worth one tenth of the monetary value of a treasure parcel of the character’s level. Failures accrue as normal.

Other Approaches

Skills are not the only way to confront the enemy, and there are indirect ways to help.

Stand and Fight (High DC): The character can simply jump into the middle of the fighting, and may roll the bonus to his basic melee basic ranged or ranged basic attack against the DC as if it were a skill. He may also sacrifice one or more healing surges before the roll, gaining a +2 bonus to the roll for each surge spent.

Lookout (Moderate DC): A number of skills, like acrobatics, athletics, insight, perception, and stealth, are not always useful in direct confrontation, but come in useful when it comes to keeping track of the enemy, and delivering messages among your allies. When a skill is used in this fashion, it is a moderate DC check, and it does not count towards the success or failure count. Instead, if successful it allows you to grant another character who is acting this round a +2 to their check. On a failure, the character loses one healing surge.

Triggers

Fighting begins with the gnolls outside the southern walls of Fallcrest, and each failure brings them closer to Moonstone Keep.

The walls are overrun! (triggered by first failure): After the first failure, the gnolls will be inside the walls, fighting and looting from street to street. This changes the utility of some of some skills for the challenge, and moves the fighting to the cliffside, trying to keep the gnolls from moving to the lower city.

To the keep! (Triggered by the second failure): After the second failure, the gnolls have made it down the cliffs to the lower city and are now pressing at the gates of Moonstone Keep.

The gates cannot hold! (triggered by the third failure): The gates of Moonstone keep have fallen, and the players have failed. They now must face Whitemane and his vanguard.

Casualties of war (triggered by a second failure in a single round): The players do not accumulate a failure, but an NPC ally falls in the defense of the city. They may not be killed outright: it is possible they are captured or cut off from the main body of troops: but their ultimate fate is now tied to the outcome of the skill challenge.

Players may wish to try to rescue particularly well-loved NPCs. This is a moderate DC check (usually streetwise, nature or stealth) if the success only recovers the NPC, and does not count towards the challenge. If the rescue also strikes at the enemy, it’s a high DC.

Ultimate Outcome

Success: The gnolls are held at bay, and you manage to catch up with the retreating Whitemane and his guards. This encounter is one level above the party’s level, and the enemy units are placed before players decide where their characters are coming from. The damage to the city is serious, but recoverable.

Failure: The Gnolls have made it into the gates of Moonstone Keep, with Whitemane at the lead. Still, if the characters can kill Whitemane, the invaders will fall into disarray. This encounter is three levels above the party’s level, and the DM doesn’t need to place his units until after the players do so. If the characters win this fight, they manage to save Moonstone Keep and those within, though the city has still been ravaged.

Some Thoughts

- In retrospect, this would benefit from a table of what works and doesn’t work depending upon which failure we’re at. The narrative is pretty simple, but I think it’s obscured within the the text, and it goes something like this:

Before the first failure: The gnolls are outside the city walls. They can be skirmished with, or the city can be made ready for the invasion.

First failure: The gnolls breach the walls.

After the first failure: The gnolls have breached the walls and fighting is happening in the upper city and pushing towards the lower city.

Second Failure: The gnolls push down the cliff from the upper city to the lower city.

After the second failure: Fighting in the lower city as the Gnolls besiege the keep.

Third Failure: The Gnolls breach the keep.

- Note that one way or another this ends in a fight scene, albeit one that is slanted in favor of or against the PCs. I feel pretty confident that by the time things reach that point, players will be gung ho for some straight up action.

- I sincerely hope, but am not entirely sure, that the scenes that I consider implicit in a lot of these actions comes through. For example, I consider the Athletics actions to be something of a gimme for how to play out. Someone has a crazy plan that just might work, a heroic PC takes a handful of troops to try to pull it off – that’s exactly how it should go.

- This would benefit greatly from a bit more guidance on how to run scenes as subsets of a challenge. I actually did write some stuff about that, but that doesn’t help here. The bottom line is that you can run a scene however you like, be it a fight, a roll, some roleplaying or even another skill challenge and then take the final outcome of that seen and “roll it up” as a success or failure in the larger skill challenge. To use the athletics example again, I could do that as a scene with an athletics/stealth skill challenge followed by a fight, with victory in the fight translating into success and defeat into failure. Basic “Dungeon as Skill Challenge” kind of stuff.

- This challenge favors the PCs. Given the way failures are handled, they will probably win it, and that’s as it should be. What’s important (and much more up in the air) is what the price is going to be. The Casualties of War trigger is in there explicitly to turn failures into pain for the characters, so that you can have them win, but still pay a potentially hefty price for it. I’m a huge fan of this model, but it’s not always easy to pull off.

- And, obviously, all this assumes an existing investment in Fallcrest. If you don’t have such an investment, then this is an interesting exercise, but it has no teeth. This is designed as a culmination of events in play, after the characters have found allies in the town, have come to hate Whitemane and have already gotten well and truly tied into the events leading up to this.

Anyway, I may post more of these later if there’s an interest, but for the moment, feel free to deconstruct at will.