Caveat before all of this begins – the material I’m about to use is sourced from a psychology paper on values which were used as the source for the diagram in a Common Cause article. I lack the expertise to speak on its value as psychology, and am really just looking at it through the lens of narrative and games.

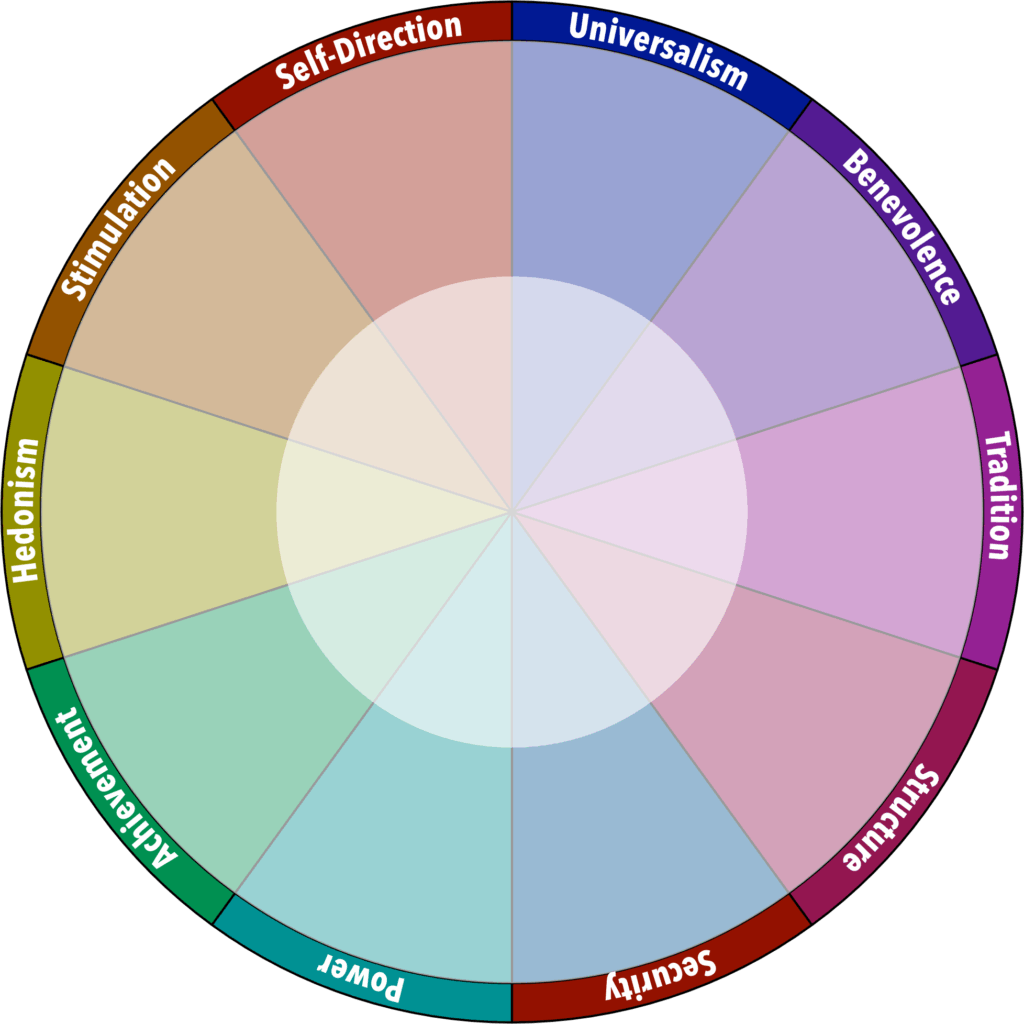

Ok, let’s start with the wheel of values:

(Yeah, I have no color sense)

Let’s start out with the idea that this is an alternative to an alignment chart. Rather than choosing good or evil (with people self-describing as evil, which never feels terribly authentic to anything), this keeps the simplicity of that sort of diagram, but with a little bit more nuance and and helps create ideas that can clearly be in conflict, but are still justifiable. Pick two values as the things that your character values most by default. Apply it across your game in the same way that you would usually find things like “Chaotic Evil” and see what it does to your thinking about “evil” races and horrible villains.

There are a couple interesting tricks at work here:

- These are all reasonable values. They could all be part of the story that one tells themselves to get through the day. It is easy to see terrible (or great) things done in pursuit of these values, and some might be categorized as more “good” than others (though even that decision is interestingly telling).

- While some of these values may be in tension with others, there is no negation. Proximity around the perimeter roughly maps to how aligned the ideas are, but only very roughly, and all of these are things which reasonable folks will value. As a result, this exercise is not about saying that any of these are unimportant, only in asking which are the most important in context.

With that in mind, here ere are two concrete tricks for using this map.

Broad Strokes

First and foremost, the list of categories is conveniently ten items long, so that makes it easy to roll against:

- Achievement

- Benevolence

- Hedonism

- Power

- Security

- Self-Direction

- Stimulation

- Structure*

- Tradition

- Universalism

* – This one is “Conformity” on the chart, but I kind of dislike the word as a category. Looking at the values that fall under it, this seemed a better match, and “Conformity” seems more like a sub-value under that.

If I’m sitting down with a map of nations or cultures and I want them to have a little more “oomph” than Magiclandia, two rolls on this table can immediately give me the two values that are most important to the group. A single roll would probably be a bit dull, but two rolls creates a dynamic that makes things a little more distinct. From there, the deeper list gives me a list of values that might be in play within the groups, and continuing to lean into them in pairs whenever possible, and I can use this model at any level.

(It’s important to remember that while these values might not align, they don’t *negate*. Any group will value all of them – this is simply a function of what is prioritized. )

Obviously, I can do the same thing for any character I’m looking for motivation for, and it becomes even bro interesting if I use these virtues as a cultural context in which to *place* individual values.

The Roots of Villainy

This is the real secret sauce – there’s an old line that every good villain is the hero of their own story, and I’m a big fan of that line of thinking. When the motives are villainous, it’s easy to end up with dastardly, cartoonish figures. These can be fun, but more substantial adversaries are driven by understandable motives, like love, justice or pride.

Rather than just say “it’s intuitive”, let me unpack that a little bit. When you have a villain who is built upon a recognizable value, it becomes easier to use them in stories and games for a few reasons:

- It is more reasonable that they can find allies without resorting to “evil minions”, because there are people who share their values who might be willing to overlook some of their choices for the sake of those values.

- It is easier to figure out what the villain might do when stymied by the heroes. Without values, they can just skip from Evil Plot to Evil Plot. With a driving value, they have something to continue to strive for.

- They are potentially more sympathetic. This may or may not be desirable, depending on your situation, but by tying their motives to understandable values, it becomes much more likely that your players will at least be able to understand why they do what they do.

- Interactions can be more complex. This sort of builds on sympathy – if the villain has an understandable value, then perhaps they can be reasoned with based on that value. Or perhaps their motives are reasonable enough that opposing them introduces challenges to the players own motivations.

- Resonance is awesome. This is one of the reasons I suggest always using at least two of these. When the villain shares a value with a hero, that opens up all sorts of fun possibilities.

Is this necessary? Definitely not. Is it maybe a useful trick? I hope so.

Where this came from

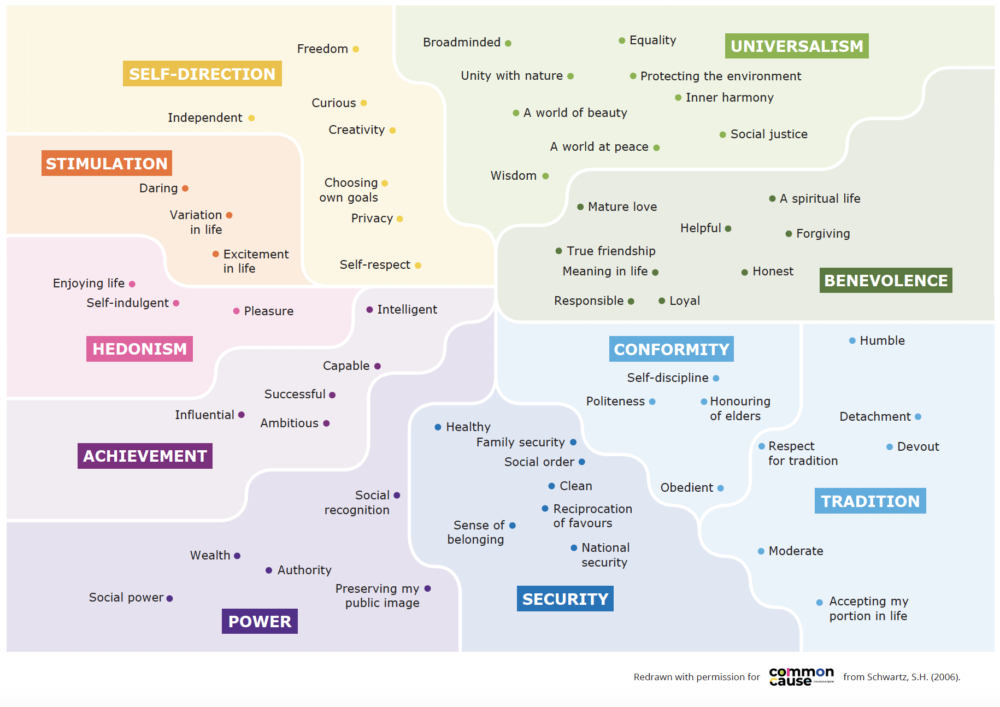

So, this all started when I saw this diagram:

It’s a lot to look at, but it’s largely a visualization of a number of lists, attempting to put the various elements in proximity. It’s a diagram of 58 individual values (like Intelligence, Self-discipline, or National security) divided into 10 categories (Conformity, Security, power and so on). This is a pretty fun list all by itself, but the point of putting in a diagram is to give a ballpark proximity of these ideas, and to illustrate the ways in which these values can come into conflict. The idea is that the closer any two values are on this map, the more likely they are to be in conflict.

There’s some other cool stuff in the research that talks about how these can shift around within a person or a culture, and it’s really fascinating stuff, but what jumped out at me as I saw this is that it looks and feels like a map of motivations.

Specifically, there’s a lot of meat in here in terms of values that fall under the umbrella of the larger value, and I suspect my next step will be mapping these into more gamey terms (and into a number of items to support die rolling)

interesting.

using this for cultural values rather than just alignment is very interesting, because it can set up some cool tensions between the two—characters who are examples of their culture’s values va ones who are iconoclasts.

I also really like the notion of putting two traits in tension. it really does avoid the “Planet of Hats” syndrome.