Yeah, It’s kind of like that.

When I started this, I was going to do a point by point readthrough of the new edition of 7th Sea in excruciating detail, and I got about 120 pages in before I realized that there were so many little things that raised my eyebrow that the whole tone was feeling more negative than I would have liked. It’s not that those concerns weren’t valid, but a lot of them were different reflections of the same underlying issues, and it was harsh for it to keep getting dinged for those. As a result, I’m zooming out a bit. This still won’t be short, but it won’t all be bullet points either.

I come into this game with a lot of baggage. I loved the first edition of 7th Sea, warts and all, and I’ve been watching development, even going out of my way to avoid spoilers. I am going into this with some hopes which I took a moment to write down before I started reading:

- Setting changes that makes pirates make sense. I’d also be happy if the archaeology angle made more sense too, but I’m equally ok with that falling down a hole.

- PCs being awesome, not just in the shadow of badass NPCs

- Less dumb metaplot

- Things that make secret societies cool out of the box rather than leaving them to be surprises, whether good (Die Kreutzritter) or terrible (Daughters of Sophia)

- No character build options predicated on “Suck now to be ok in 25 sessions or so!” (that is to say, the way swordsman schools were handled)

- No forcing players to spend XP

Of those 6 things, we have 3 solid hits, and 3 TBDs based on the splat strategy, so that could be worse.

The main thing I discovered is that familiarity is the most dangerous thing in this book. For me, it made it hard to read the setting without my knowledge of the previous edition. In many games that would not be a problem, but first edition 7th Sea was rife with secrets whose explanations were deferred until the splatbooks came out. In some cases those splatbooks upended previous understandings of things (this is not a great practice in my mind, but it sells books). As a result, when faced with a high level information, I tend not to trust it, wondering if it’s just a facade waiting for the reveal.

But I do not know if that’s fair or not. The splats haven’t come yet. It’s entirely possible that they’ve discarded the deep and abiding metaplot, and I am worrying about nothing. I hope that’s the case. This new edition gives players some wonderful new tools for shaping the world, and big metaplot would be all the worse for it.

So I am trying to set aside my wariness, but even with the most generous read, it is hard not not notice what was done differently, and ponder what priorities that represents (not necessarily in a bad way). Such changes are a flag of creator’s intent, so I cannot help but be curious about it.

Ok, enough meta-analysis: How about the book itself?

The Book

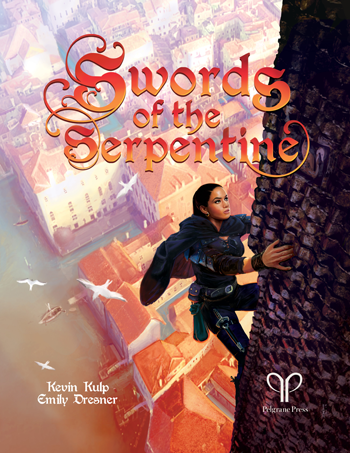

It’s nice! Solid, full color glossy paged hardcover. Cover image is striking. I’m not sure it’s my imagination that the dude (in secondary position behind the lady swashbuckler, a lovely touch) looks a little like the cinematic version of John Wick and I’m good with that. Page design is functional – very straightforward colophon, minimal page decoration. Layout mostly gets out of the way – a little bland, but that’s better than the alternative. Lots of browns, though, which makes it feel a little d20ish.

The art is quite good throughout. I won’t call out favorite pieces, but I want to give especial notice for the chapter separators. Each chapter opens with a full color two page spread, and they’re lovely and striking. It’s also diverse and interesting – there’s a nice analysis of the art available if you’re interested.

That said, the index is terrible. It’s maybe a page and a quarter long, which is dreadfully short for a book of this size. This problem is exacerbated by the fact that a lot of terms and ideas are used before they’re explained, so if the reader decided to check the index to figure out what’s being talked about, they will probably come up dry. As I was reading, this was kind of maddening (and lead to a lot of “Nope, not in the index” bullet points.)

What’s Changed

There is no equivalent of the nation pages from the original edition. This would not normally merit mention, but they were so striking and so essential to the sense of the original game that their absence is noteworthy. However,the art throughout the book is in color and of good quality, so the absence is not a problem if you aren’t looking for it.

The Map

It’s lovely. Looks like an actual map, with actual stuff on it. It’s in the frontspiece but not the back, which seems odd, but not a big deal. There’s also a less accurate map in the main body of the book, so there’s a more handout-suitable version. However, one downside of such remarkable mapwork is that it makes the absences stand out. There are numerous references to more distant nations (ones which are getting their own books) but they’re outside of the scope of the map presented, so I’m left quite confused as to where they’re supposed to be, which becomes an issue when they talk about how they interact with the nation of Theah.

What’s Changed

At first glance, the map seems vaguely similar to 1e, but that’s mostly because the 1e map was a lot of blobs squished together. There have actually been some substantial changes to geography since 1e, most notably with Montaigne & Castille put in less proximity to one another, and Eisen placed in such a way that it makes a lot of sense that all the armies of Theah have battled across it. Vesten is no longer islands, but rather a scandanavian-style peninsula. The addition of the Sarmatian Commonwealth east of Vodacce pushes the Crescent Empire a little further west and does a better job of isolating it from Theah than CRPG style impassable mountains. Cathay now appears to be the steppes rather than magic China, but there’s some inference in that conclusion.

Introduction

The opening fiction is about twice as long as it needs to be, and suffers from a flash-forward opening without payoff. It’s not bad, certainly, but the bar for the very first story is high.

The game text opens with a list of the things the Game is about: “Swashbuckling and Sorcery”, “Piracy and Adventure”, “Diplomacy and Intrigue”, “Archaeology and Exploration” and “Romance and Revenge”. I could probably quibble with the various descriptions of these things, but I can’t fault the game for laying them out there.

The “What is an RPG” stuff which is pretty boilerplate. Interestingly, the “Rulings vs. Rules” sidebar (which I agree with) reads like “This is where we would mention rule zero, but we cannot actually say rule zero”. There’s also some advance notice that the GM section is full of tips and tricks, which is no surprise to anyone who digs John Wick’s stuff. I’m certainly enthused to get to it.

It rounds out with the super-high-level review of the setting – list of nations, and the single paragraph on key concepts like the church, secret societies. This is where some places outside of Theah get mentioned, but they use colorful terms rather than the actual names used elsewhere in the book, which introduces some undue confusion.

What’s Changed

The addition of a new nation (The Sarmatian Commonwealth) was fairly loudly previewed, so it’s inclusion on the nation list is no great shock. What is surprising is that rather than one Avalon entry, we have 3, one for each of the isles (Avalon, Inismore and the Highland Marches). They remain similarly privileged for the whole of the game. When I mention trying to suss out intent from changes? This one here is a big one.

Setting

Very first point in the chapter is about diversity – men and women as explicitly on much more equal footing. More vaguely, race is kind of less of a thing, with nationality being more important than skin tone. It’s a little awkward, but it’s faux-europe, so it’d kind of have to be. Full props for putting it front and center.

What follows is an entry for each nation: Avalon, Castille, Eisen, The Highland Marches, Inismore, Montaigne, Sarmatian Commonwealth, Ussura, Vestenmennavenjar and Vodacce. The entries span from 5 to 10 pages in length, and follow a general pattern of loose history, current events and culture (covering topics from Names to religion to etiquette to Food). Some entries also cover politics and geography, some do not. It ends with a page of their opinion of other nations. Notably, the Pirate Nations get referenced here, though the game is officially treating them as a secret society.

These are, frankly, a little uneven. There is a trick to writing setting material in such a way that it conveys information but also gives you immediate hooks to play. Miss that mark too much to one side and you get an almanac entry. Miss too much to the other, and you have style without substance. Threading that needle is tricky, and the various entries do it to varying degrees.

7th Sea has an extra challenge in this regard, because it is modeled on a simplified version of history that largely works because it resonates with stereotypical images in our minds. That is a great trick, but it needs to be taken into account. Re-explaining the stereotype is a good way to waste words.

Ok, with that said, let’s dive in.

Avalon is faux-England, with an Elizabeth analog (Elaine) having taken the throne by virtue of holding the Holy Grail equivalent, something that also brought Glamour Magic back to the isles. Elaine rules Avalon, Inismore (Ireland) and The Highland Marches (Scotland) and it’s largely all going pretty well with only a few tensions beneath the surface. She also runs the Church of Avalon, but that doesn’t seem to be too much of a big deal when contrasted with the Objectionists (protestants) on the continent. In splitting Avalon into 3 nations, they ended up removing some of what would have made the Avalon entry interesting, and it reveals that by itself, Avalon is a little dull, though they do fund a lot of pirates.

Castille (Faux spain) is nicely set up. It should be an awesome place. They have great infrastructure, big friendly families, plenty of resources and all the other things that could make for a pretty good life. Except it’s taken a triple blow – it just fought off an invasion from Montaigne, so that took a toll. The Vaticine Church, which has its seat in Castille, is currently leaderless, and the Inquisition runs amok. And the young king is weak, and is being (metaphorically) shackled by the Cardinals who are supposed to advise him. As a result of these problems, decay has set in at every level.

It’s a good setup. Lots of wrongs to right, all of which are firmly grounded in very human experience. Castille is the kind of place where heroes can make a difference, and also illustrates that you don’t need Deep Cosmic Mysteries to drive play.

That said, my one niggle is that the whole nation reads as very rural. I am enough of a Captain Alatriste fan to really want to get a bit of Madrid into my play, and there’s not much there.

Eisen (Faux Germany) is Ravenloft, or as close as you’re going to get on Theah. A 30 year religious civil war has utterly wrecked the place (population was 24 million at the start of the war. By the end, 6 million had emigrated, and the new population was 10 million. That’s some wicked arithmetic.) Now it’s something of a blasted shell of itself. There are still places that are largely intact – cities and strongholds especially – but outside of those, there is a lot of monster haunted wasteland.

One curious thing about the death rate: The fighting was largely done by mercenaries. As such, it’s worth explicitly noting that battle can only account for a fraction of that kind of death rate. Disease and starvation are likelier candidates, but this is the kind of place where “Monsters” may also be a big contender.

On a personal note, I recently finished playing The Witcher 3 (awesome game) and tonally, if would fit in Eisen very well.

The Highland Marches (Faux Scotland) is exactly what you’d expect. I read this section 3 times and it just slid off my brain each time. They’re temperamental but honorable clans with kilts, claymores and boiled food. Everything kind of expands that. And lest I sound unkind, I went in eyes open – it struck me that this was a great avenue for Outlander fans, so I was hopeful.

Innismore (Faux Ireland) is supremely romanticized. I knew this would be tricky, and it was. My family is Irish, so this is the part I theoretically identify with, but it is so romanticized that I very nearly injure myself rolling my eyes. Which is unfair. It bugs me, but this one is totally my bias, so it gets a pass.

Montaigne (Faux France) gets bigger page count than anything else, which reflects its importance in the setting pretty well. Technically, this is a good write up – we actually get some geography and a solid sense of how the nation works, as well as its driving conflict (nobility vs Peasants). There are some oddities (the rigid, simple class structure ends up sounding like “robust middle class), but it’s all there.

Yet for all that, it’s a disappointing section for tonal reasons. it feels like it was written by someone who really doesn’t like Montaigne. The nobility are cartoonishly bad, and the subtext of “La Revolution is coming” is such a loud drumbeat as to overwhelm all other things. And I totally get it if that’s the story someone wants to tell, but I’m in this for Dumas, not Hugo.

Setting aside tone, it means that almost nothing worth swashing a buckle over gets any real emphasis in this section. The section on Musketeers is shorter than than the section on clothing. I would really want each of these sections to be “reasons I’d be excited to play someone from here” and this one is more “Well, I guess, if you want.” T

Sarmatian Commonwealth – So, this one’s interesting because I have no clear analog for it. The Commonwealth pulls from many sources including Poland, Austria-Hungary and a bit of “European” Russia. Someone with more of a grasp of Eastern European history may see something as much clearer, but I’m viewing it as something of a goulash.

The Commonwealth is really nicely set up. It has a geographic and cultural divide between the two nations that compose it, and it’s just had a flashpoint moment that has converted the country to a sort of democracy by fiat, and there is a lot of questions regarding whether or not it’s sustainable. Oh, also there are devils in the woods who offer deals to the unwary. Plus Cossacks. These are good things.

All in all, a fun section. Also, notably, it’s entirely unhindered by past knowledge (since this is a new addition to the setting), I could enjoy it without hesitation.

Ussura (faux Russia) is backwards and magical. It’s a little weird. The land is alive and protects her people. Historically, it has driven off all attackers. They don’t even need to keep up an army, I am not sure how I feel about that – it is kind of hard to spin a narrative of how hardy the people are when it’s magic that lets them thrive. It ends up feeling less like a nation and more like a fairytale land. That’s fine – just as Eisen is the place for one type of story, Ussura is the place for another. As presented, the political conflict (over succession of the Czar) feels badly matched to the nation, but thankfully it’s also not given a lot of spotlight.

Vestenmennavenjar (faux Skyrim) – used to be vikings but then realized there was more money in trade, so they’ve gone after that, but there’s still some viking-ness afoot.

The Vesten are nicely set up as an influence in the world, but unless you’re interested in the viking stuff, they seem best set up to exist somewhere else. That’s not a bad thing. It improves the world, but it kind fo does so at tis own expense.

Vodacce (Faux Italy) – this section is a profound contrast to the Montaigne section. Both of them begin with the premise that their nobility are a bunch of jerks, but where Montaigne just sighs and looks sad about it, Vodacce is all “Isn’t it AWESOME?”. I fully admit, the latter is more of what I’m looking for in a setting.

And in this case, it’s italianate city states with constantly infighting nobility and profound, deeply rooted sexism. Given the material, the content is a little dry, but it is more than carried by the clear enthusiasm for it. It’s fairly obvious that this is a big dollop of fun being added to the stew of Thea

What’s Changed

Aside from the addition of the Commonwealth, a few interesting things popped out:

- Generally, everything feels more magical. We’ve now got 4 nations (Avalon, Vesten, Usurra & the Commonwealth) where it is expected that there are magical being walking around doing stuff. “Magic is bad” is still present, but it seems greatly downplayed.

- No mention of the White Plague. Curious.

- Giving the Inish and Highlanders places of prominence but otherwise ignoring the idea of smaller nationalities seems weird.

- Only passing mention of Los Vagos (Now Los Vagabundos) in the Castille section. Seemed odd, but apparently they’ve gone global.

- Eisen was always grim, but it seems like it’s really made the full jump to horror. Which is kind of cool.

- Ussura seems explicitly more magical in terms of the land protecting her people. This had been nodded to previously, but it now seems pretty much front and center.

- Ussura also seems a lot smaller. It also seems like the setting for a handful of Disney movies.

- The Vesten feel a lot less dutch, for good and ill. They seem to be wearing less black, which makes me sad.

More Setting

After the nations, we get into other elements of the world. We get an overview of what the Seven Seas are, what the courts of Theah are like, and what the Duelist’s Guild is (and implicitly, how duels work). There is also discussion of honor and “gentles”, which is effectively gentlemanly conduct for a world where the “man” part is not required for the “gentle” part (I love the concept, but it’s a weird word).

We get a breakdown of the Vaticine Church (Faux Catholics) and some tenets of faith, very loosely sketched. We also get a sense of the Church’s power structure, how it’s broken, and why that means the Inquisition is running amok. We also get a brief overview of the Objectionists (Faux Protestants)

The next section is on Knowledge and it’s a 2 page summary of where science and technology are in Theah. Nice compact, and useful stuff.

After that, we finally get to hear about the frequently mentioned Pirates (and Privateers). We get a run down of the major pirate groups and where they do their business. After that, Secret Societies get a single page list and summary, then we’re onto Syrneth Ruins and Monsters.

The monsters are…well, they’re monsters. Not a lot to unpack there.

The Ruins section explains that the world is full of hidden ruins of a mysterious lost race with potentially magically steampunky artifacts. We get a writeup of some big ruins (under Vodacce and the capitol of Montaigne) but there’s a lot of handwavium here.

What’s Changed

- Reis is still around, though no sign of Kheired-Din

- One new secret society – Močiutės Skara – lots of good works and disaster recovery. In the big mapping of things, maybe hospitallar-ish

- I honestly do not know if the Syrneth have changed or if the metaplot is the same. They still seem to have a place of prominence in the game, but the level of detail is sketchy at best.

Chargen

Step -1: Read More About Nations – We get another summary of the nations. No contradictions, but some different emphasis. More emphasis on playability, since this is nominally the “heroes from this nation are…” section, but it also feels a bit duplicative.

Step 0: Pick a Concept – Pretty much guidance on thinking about your character. Practically, it includes 20 questions to help you think. They have no mechanical impact, and you’re not obliged to answer all of them, but the exercise of thinking through answers to a few of them seems like it could be quite valuable.

Step 1: Traits – 5 Stats (Brawn, Wits, Resolve, Finesse, Panache). Start with a 2 in each of them, spend 2 more points as you see fit.

Step 2: Pick a Nation – Each nation has two favored stats. You may take an additional +1 to one of those stats (so you can get one stat to 5 if you want, but that’s about it). Your nationality also has some impact on the cost of certain advantages.

Sidebar: That puts your total ranks of traits at 13. The highest it can ever be is 15. There’s going to be a lot of advancement in other places, but traits are ultimately pretty strongly capped.

Step 3: Backgrounds – Backgrounds are packages like “Cavalryman” or “Assassin”. Mechanically, they’re composed of 3 things:

- A Quirk that allows the player to gain Hero Points (in game currency). For the Aristocrat, for example, “Earn a Hero Point when you prove there is more to nobility than expensive clothes and attending court.”

- 5 skills which you get +1 apiece to (For the Aristocrat: Aim, Convince, Empathy, Ride & Scholarship).

- 5 points of Advantages pre-selected for you. (For the Aristocrat: Rich and Disarming Smile)

You get to pick 2 backgrounds. If a skill shows up twice, you have it at a 2. Nothing is explicitly said of what happens if you have a duplicate advantage, but personally I’d offer a same-value trade in (edit: apparently that is the correct rule, I just failed to read it. thanks Longstrider!) . Notably, there are a number of nation-specific backgrounds, which work the same way, but take the nationality discounts into account. More on that when we get to advantages.

The backgrounds are interesting because they are mostly critical for the Quirks. The skill & advantage component of them is trivial enough to hardly need a template. Even the nationality-specific backgrounds are a bit of sleight of hand to help privilege national gimmicks. But despite the fact that they could be disposed of, they seem like friendly guideposts, and provide copious opportunities for people to hack up their own. Always valuable to make sure that such hooks exist.

Also, cynically, it’s the only way some advantages are ever going to be bought.

Step 4: Skills – So at this point, you have 10 points of skillsfrom backgrounds, and now you have another 10 points to spend. The catch is that at this point, no skill can get higher than 3. That feels kind of like a screwjob, but it’s balanced by the fact that skill ranks are not a straight progression. Yes, you roll a die for each rank, but you also get special tricks (which are cumulative) at 3, 4 and 5 ranks. At 3, you can reroll one die. At 4, you build sets more efficiently (more later), and at 5 your 10s explode.

The skill list itself is super straightforward. Aim, Athletics, Brawl, Convince, Empathy, Hide, Intimidate, Notice, Perform, Ride, Sailing, Scholarship, Tempt, Theft, Warfare and Weaponry. With 20 points to spend, it’s possible to cover all of them, and with a 3 point cap, you’ll probably have a decent spread. It’s worth noting that the penalty for acting unskilled is quite harsh, so there’s some value in skills at 1, but at the same time, it is more time consuming to pick up higher skill ranks in play, so decide where you want to trade off.

Step 5: Advantages – Advantages cost from 1 to 5 points, with their effect scaling appropriately. In addition to the 10 points of advantages you got from your backgrounds, you have 5 more points to spend as you see fit. This is an interesting arrangement because it means that you can afford any one thing, no matter what your backgrounds. It also introduces some rough math around the 3 point mark, because it’s hard to say that a 3 pointer and a 2 pointer are really worth a 5 pointer. But such are the dangers of point buy.

The advantages themselves are pretty straightforward, ranging from “Able Drinker” for one point to “Duellist Academy” for five points. There are a handful of advantages which require a particular nationality, or offer a discount for a particular nationality.

Of note, each nationality has what appears to be a signature Advantage. Most of the 5 point advantages can be bought for 3 points if you are the correct nationality. “I Won’t Die Here” is normally 5 points, but is only 3 if you’re an Eisen. (This is also why in the Eisen-Only background “ Monster Hunter”, you get I Won’t Die Here and Indomitable Will, a combination which would cost 7 points for anyone else.) It’s a colorful list, but by its nature, it can only grow with time.

One curiosity: There’s a “Foreign Born” background for one point, which lets you buy advantages as if you’re from the second nation. For a lot of mid-tier stuff, this is breakeven – the 1 point discount is offset by this one point cost – but it does allow for a character to have 2 signature advantages if they want or open up “locked” advantages, like Alchemist (4 points, Castillian only).

What’s Changed

The whole mechanical system is new enough that I’m not going to call out much, but I figured I’d answer a few questions that might be in people’s minds.

- Swordsman School costs 5 points. That is very expensive, but the payoff is huge. Swordsmen profoundly outclass non-swordsmen in any fight. You can buy it again for multiple schools, but the returns are drastically diminishing, and don’t stack. It tends to give just one more option.

- Sorcery costs 2 points, and it’s expected it will be bought multiple times. What that means depends on the specific Sorcery.

- No amount of points will let you start with Dracheneisen. It is now insanely rare and jealously guarded.

- Castillian education is no longer really a thing. Their national advantage is Spark of Genius, but it doesn’t come close. Castillians do get unique access to Alchemy, though, presumably to offset their lack of sorcery.

Step 6: Arcana – The Sorte Deck is a tarot-like deck of cards with a number of Major Arcana (The Fool, The Magician and so on). Each card has a Virtue and a Hubris, and each character will also have a Virtue and a Hubris. The Virtue is some unique ability you can trigger once per session (often with a cost). The Hubris is some circumstance under which you gain Hero Points (not unlike a quirk) which you can only trigger once per session, but which the GM can offer you the opportunity to trigger as much as you both like.

Curiously, you do not pick a card, but can instead cherry pick a Virtue and a Hubris. So I can choose my virtue from, say, The Fool (Wily: Activate your Virtue to escape danger from the current Scene. You cannot rescue anyone but yourself. – John Rogers and my Wife understand why) and my hubris from the Wheel (Unfortunate: You receive 2 Hero Points when you choose to fail an important Risk before rolling.).

It surprised me when I realized I could cherry pick rather than be bound to a card, and that seems to complicate some Sorte (fate magic) stuff a little, but all in all I kind of like it for promoting more combinations.

Step 7: Stories – The first time you make up a character, just to test out the system, there is going to be a HUGE temptation to skip this section. At first glance, it seems similar to the 20 questions early on – helpful, but not essential. Don’t Do That. Skipping this is skipping over one of the most interesting pieces of game technology in 7th Sea.

Stories work like this: The player starts with a concept for their story, then writes down some goal they want their character to accomplish. The player is acting very much as the author of their story in this way, so they write down this ending as they would if they were drafting the novel.

Then, from there, they reverse-engineer an outline of story beats that get to that point. It might be as short as one or two steps, or it might be a grand, epic arc, but at the end, it’s effectively a checklist of things to do.

This is pretty potent stuff. The player is effectively writing the sketch of the adventure she wants and handing it to the GM. That’s pretty huge, and it’s worth noting that there’s some sweet bribery attached to this. Stories are the currency of advancement. Want a 4 points advantage? Then you need a 4 step story that culminates in a way that would make sense for you to get that advantage.

To steal an example from the book:

John Doe has amnesia, but is actually a prince, so his story ends with him rediscovering his identify. The steps of the story are:

- Return to the town where he was found, amnesiatic and lost, and investigate.

- Meet princess Mary and see if she recognizes me.

- Return to court and plead my case before the Queen

Once all three steps are done, the story completes, and the character now has picked up a 3 point advantage (in this case, Rich).

Now, there are qualifiers and tricks and ways to deal with things going off the rails, but its important to note that there’s a HUGE amount of player authority in this. Princess Mary may well be an NPC the player created, and the player is more or less saying all these things are true.

I love this. It won’t be everyone’s bag, and that’s cool, but I LOVE it. However, there are two things that kind of go unsaid in the text that I want to call out.

First, this only works well when the GM respects it. The GM has her own stories to tell too (literally – the GM has a similar tool) and there’s a lot of trust extended here.

Second, this is an amazing collaborative opportunity. I cannot imagine the players creating their stories in isolation when they could create them together, borrowing elements and inspiration from each other. Honestly, I look at the folks I would play 7th Sea with, and were I to let them sit down and sketch out their own stories together, they’d build a campaign that would put anything I can think of to shame.

I am SOOOOOOO excited by that prospect. More than any other thing in this game, that makes me want to sit down and play as soon as possible.

Step 8: Details – At first glance this looks like it’s just bookkeeping stuff – your reputation starts at 0 unless there’s some reason it doesn’t, you speak a number of languages equal to your wits and OH BY THE WAY, this is how you join a secret society, spend money, and don’t die. Which is to say, this is a bit of a catchall bucket.

They made a wonderful choice with Secret Societies that can be boiled down to this: joining a secret society is free. There is literally no reason not to be a member of some group, and the individual benefits are pretty worthwhile. The only downside is there’s no particular guidance for doing secret society-centric games (where everyone is a member of the same society). That is an obvious mode of play, but the benefits of membership scale somewhat sloppily.

Wealth is handled in an abstract fashion – heroes always have enough money for the basics but spend “Wealth Points” for extras. Notably, there are skills for earning money (and later on, buying and selling cargo) so if that’s your itch, it can be scratched.

We wrap up with the handling of wounds, which work the same way for anyone who has not bought specific advantages that change it. You have a wound track that’s 20 boxes long. Each wound fills in a box. Every 5th box (#5, 10, 15 & 20) represents a “dramatic wound”. Wounds clear quickly, but dramatic wounds take a little bit of extra effort, but they’re not a huge deal.

As you accrue dramatic wounds, there is a curious see-saw effect. If you have 1 dramatic wound, you get a bonus die on all actions. if you have 2 dramatic wounds, villains get 2 bonus dice against you. If you have 3 dramatic wounds, your 10s explode. If you have 4 Dramatic Wounds, you’re helpless.

Importantly, helpless is not dead. To make you dead requires very specific action on the GMs part that requires spending currency and acting through the hands of a Villain. Which is to say, death is not much of a threat in the game – and that’s a good thing, because that allows so many better threats.

The Actual Freaking Rules

Ok, the core mechanic is super simple. First, only roll when it matters. This is a rule in all games, but really they mean it here. When the dice his the table, shit happens. Be prepared.

For most actions (called “risks” in the 7S lexicon), you roll a pool of d10s based on your Trait plus Skill. Simple enough. After you’ve rolled, you build sets that total up to 10 or more. Each set constitutes a “raise”, which are the currency of action. Any action you want to take requires spending a raise.

For Example: I need to chase a guy through a market square. That’s probably Finesse + Athletics. I have a 2 finesse and a 3 Athletics, so I start off with 5 dice. I roll and get 8, 6, 5, 3, 1. Because I have a 3 Athletics, I can reroll one die, and I reroll that 1 and get a 5. I build my sets (8,3 and 6,5) and the other 5 is wasted. I have 2 raises to spend.

Now, interestingly, there’s no “difficulty” to speak of. If I want to do a thing, and I have a raise to spend, then I do the thing. Which seems potent,because it is. But the GM also has some too use instead of difficulty: Consequences and Opportunities.

Consequences are bad things that are going to happen if the hero doesn’t stop them. The simplest consequence is damage done to the character, but really they could be almost anything. It’s a bit of sleight of hand, since practically, this ends up serving as a stand in for difficulty, especially if the consequences are particularly severe. You generally need to spend raises to cancel out consequences.

Opportunities are bonuses available in the scene that can be grabbed during action if there are raises available to do them. They are not required, but they offer a way for GM’s to tease the player with temptation. Sort of “You can afford to succeed free and clear, or you can take some consequences and also get the shiny thing!”.

The player can also get extra dice from Flair. These rules are akin to Exalted’s stunting rules, and are bonuses you get for being cool. The first time you use a skill in a scene, you get a bonus die. If you describe your action colorfully, that’s also worth a bonus die. The bar for getting both of these is pretty low, so it should use pretty hard.

For Example: Gaston has sworn to drink a bottle of wine at the top of the church in the middle of the battlefield. This is dangerous and foolish, but absolutely appropriate. Opposing enemies are shooting back and forth across the battlefield. Plus, it’s a VERY nice bottle of wine, so it would be a shame if anything were to happen to it. This sounds like Athletics plus Panache, (3 + 3), plus two for Flair. Gaston’s player rolls 10, 8,7, 5, 5, 3, 2, 2, rerolls a 2 and gets a 4. That’s 4 raises (10, 8+2, 7+3, 5+5).

The potential consequences of this action are injury (4 wounds) and the loss of the wine bottle. However, there is also an opportunity – another musketeer is willing to bet on the outcome, so there’s some cash payout as well as bragging rights. So Gaston’s player can spend raises as follows:

1 raise gets Gaston to the spire of the church

1 raise keeps the bottle from being broken

1 raise prevents 1 wound. This can be spent 4 times.

1 raise allows there to be a bet on this effort, and upon return, Gaston will gain a point of wealth.

Gaston opts to spend one raise to succeed, one to prevent the bottle form breaking, one to make the bet, and has only one to spend to avoid getting hurt. He’s cut by concrete shards from a near miss, but successfully drinks a toast to L’Empereur from the heart of the battlefield.

This could be complicated further by Hero Points, metacurrency (like Fate Points) that players can use for all kinds of fun things like activating abilities or granting myself a d10. My favorite element about them is that if I spend one to help someone else, it grants 3d10, so there’s always big benefits in teamwork. But be warned, the GM also has a pool of Danger Points, which can be used for all kinds of dastardly things. The GM tends to start with a fixed pool of DPs, and the only way to gain them is to buy off unused raises from players, giving them hero points to gain the same number of Danger Points. It’s a clever mechanic because it theoretically lets players throttle it, but I’m not sure how it actually shakes out.

Ok, so that was a simple action (or “Risk”, in the vernacular) involving one person rolling one die. There can also be group scenes where everyone throws their raises at the problem at hand, and they work roughly the same way.

Where it gets interesting is when there is actual opposition, in the form of Villains and Brutes, or other complications (like monsters) that actively work against the players.

Brutes are interesting because they’re ultimately a passive threat with a given rating. By default, they don’t do anything, but at the end of a round, they inflict damage on heroes equal to their rating, so there is strong incentive for heroes to whittle them down while doing other things. Villains, on the other hand, generate raises and use them to do things like damage the players or complicate the situation.

Practically, this means everyone declares the kind of action they’re taking and rolls their dice at the start of the round, then starting with the person with the most raises (villains win ties, players decide amongst themselves) spend one or more raises to take an action. Once the action is taken, the new person with the most raises goes first.

This is an interesting system, but one with some gotchas. The first and most critical is to notice a small rule: If you take an action that it outside the auspices of what you originally rolled, then you need to spend an extra raise. That is, suppose you started the scene by saying you are using Wits + Convince to distract the bad guy, but then when the ceiling starts to collapse, you need to dodge out of the way. Normally that would take only one raise, but since Convince is not super helpful for dodging, it will cost one extra, or two raises.

There is a very well articulated example scene in the book that goes for three and a half pages and highlights both the highs and lows of the system. It’s very dynamic, but it also illustrates how far afield a scene can go to go over the course of things, especially because the fiat ability implicit in a raise spent on changing details is very broad (in fact, the GM uses it in the example to kind of crappily negate a player’s success, then drastically change the situation).

Ultimately, the strength of this kind of system is that it’s very freeform and dynamic, but the downside is that it can end up feeling like an accounting exercise. There are some decent checks to keep play moving (most specifically that there is no hold action or equivalent, which would KILL THIS GAME DEAD) but it also is very clearly a situation where a particularly crappy roll could ruin a scene for a player. Ultimately, I really want to see it at the table.

These concerns double down for Dramatic Sequences, which contrast action sequences because they’re spread out over time rather than beat by beat. These make sense intellectually, but I worry about sequencing all the more in that sort of environment.

Game Master Rules

The next section lays out the tools for the GM.

First, it gives the rules for creating Brute Squads. These are super simple, mechanically, with the option of giving them one gimmick (like “assassins”, who strike first, or “Thieves” who may run off with stuff.)

The Villain building system is pretty interesting. Villains have 2 stats: Strength and Influence. When they roll dice, they use a pool equal to the total of those two, and that pool can be as big as 20 for HUGE, WORLD CLASS VILLAINS. Strength is pretty constant, since it’s just a measure of badassery, but influence gets fun. It can be invested (in schemes, or in minions) in hopes of a big return, unless it is quashed by Heroes. Of especial note, villains can invest in smaller villains who can invest in smaller villains, which is to say it’s pretty much a minigame designed to create a progression of villains, which is pretty cool.

Monsters might be built as Brutes or Villains, but they have an additional pool of monstrous abilities to draw upon.

This section also outlines how to create GM stories, which are structurally very similar to character stories, but with rather more guidance in how they’re created. I admit, I’m less excited about these than the player ones, and I kind of wish these tools were in the earlier section, but so be it.

Lastly, we have Corruption, which effectively serve as Dark Side points. Gain them by acting in a villainous fashion, and every time you gain one, there’s a risk of your character becoming an NPC. It’s kind of brute force for genre enforcement, but it seems like a solid threat.

Sorcery

There are several types of Sorcery, one for each nation (except Castille). You are limited to buying the sorcery of your nation.

Hexenwerk is the ability to create potions and concoctions out of gross things. It pretty much confirms that I was not the only person thinking that Theah is a good match for the Witcher, since this sorcery works perfectly for monster hunters using secret knowledge to kill beasts. However, it also works well for twisted madmen looking to do terrible things, so it’s a bit double edged. One rank of sorcery teaches one major potion and two minor ones. This is the Eisen sorcery, though there doesn’t seem to be anything that mandates that it would be so.

Knights of Avalon adopt (or more aptly, embody) the virtues of semi-arthurian knights, who given them access to magical tricks called Glamours based on the nature of the knight. Mechanically, Glamours are tied to traits or to Luck, and a given knight has access to 2 traits and Luck. One rank of sorcery gets one major glamour and 2 minor ones.

Mother’s Touch (Dar Matushki) is Ussuran folk magic, gifts from Matushki, the personification of the land. For each rank you get one gift and one restriction. Gifts include turning into animals, commanding animals, purification, regeneration (for you would-be Rasputins) and so on, while restrictions are things like Honesty or Moderation. Fun and straighforward.

Porte is the ability to rip bloody holes in the universe to pull things through, or travel. It’s gross, but stylish. One very nice touch is that heroes hurt themselves (inflict Dramatic wounds) to do powerful effects, but villains just damage the world a lot more. Very nice and playable.

Sanderis is something akin to having a Nuclear Djinn in your pocket. You have made a deal with a powerful and wicked but honest being called a dievai. By the terms of the arrangement, it grants you minor powers (“favors”) at small costs which might be annoying, but are no big deal. However, it can also grant major favors, and those are serious. Like, destroy a city kind of serious. You can ask for this any time, but it will always have a cost, and the cost will be pretty terrible (and cost a point of corruption).

But even more fun – the relationship between sorcerer and Dievai is a quiet war. The Sorcerer’s goal is to learn enough of the creature’s name to destroy it (each rank brings you one step closer and also grants more power), while the Dievai is working to corrupt the caster. Super fun. If anything, I’m a little sad that I’ll have to wait for the inevitable splat for support on how to run it.

Sorte always seems cooler on paper than it is in practice. In theory, it’s studying the threads of fate and manipulating them to particular ends. As presented, they can mess with people’s arcana, bless and curse, and pull things. Seems a little blah.

What Has Changed

- Hexenwerk and Sanderis are totally new (and are pretty cool).

- No sign or mention of the bargainers or other bargainer forms of magic

- Ussuran Magic has expanded too include a lot of general folk magic in addition to shapeshifting into animals. It also is now explicitly sources from Matushki.

Dueling

Oh, yeah, swordsman schools! This is the stuff.

Most swordsmen school offer roughly the same set of benefits – the swordsman learns 6 maneuvers which he can spend a raise to use in a fight. The most basic one is Slash – normally, if you want to hurt someone, you spend one raise and inflict one wound. If you slash, you spend one raise, and inflict damage equal to your ranks in the weapon skill. All the maneuvers are similarly overwhelming, and a swordsman is going to eradicate a similarly skilled non-swordsman, simple as that. The only real limiter on the maneuvers is that you can’t use the same maneuver twice in a row, so you can’t just slash everyone to death all the time – you need to mix it up a little.

Each school then offers one special move which can be used when fighting in the correct way (which is to say, using the right weapons) which either supplements the list, or upgrades one of the existing moves. For example, in the Aldana style, if fighting with a fencing blade in one hand, and the other hand empty, you can perform an additional maneuver, the Aldana Ruse, which adds you panache to the next amount of damage the target takes.

The school-specific moves are fun, but not so overwhelming that you MUST pick a school based on efficacy – it is still perfectly badass if you just go with the cool one.

What Has Changed

- As noted previously, the bulk of the value of the advantage comes from the base package. If you learn a new school (which requires a 5 step story or another 5 points) then all you get is a new special move. You can only use one school’s move per action, so even that is not a huge advantage.

- Because they’re shorter, there are many more schools, most of which will be a familiar from the splats.

Sailing

Sailing ends up feeling like a small collection of fun mini games. There’s the crew minigame, the trading minigame, the ship-battle minigame (which works like any other sequence, with just a few special options) and the ship-making minigame. For a non-pirate game, it’s largely overkill, but for a buccaneer, game, it actually seems kind of awesome. I think my favorite bit is that your ship can accrue CRPG style achievements for doing things like being captured by pirates or visiting a port in every major nation. These achievements become part of your ship’s “story” and grant concrete benefits. Silly, but fun!

Secret Societies

So, as noted earlier, you can join a secret society for free. This is pretty cool, and this section is where you’re going to find out a little bit more about the various societies.

The general mechanic for secret societies uses a rating called “favor”. You gain favor by do things for the society, and can spend it to get resources or information from the society. There’s a default list of things that any society wants (Useful information, Helping an agent, useful secret) and things they can provide (useful information, aid, useful secrets) and the amount of favor it earns of costs. In each societies description, they add additional things this society wants or can do. Very elegant.

In another clever move, you tend to earn more favor for a given thing than it would cost to get it, which encourages players to use these societies because they’re getting a bargain.

As to the societies themselves:

- The Brotherhood of the Coast – well, they’re pirates. they’ve got a charter and some democracy, and they can do piratey things.

- Die Kreutzritter – An order of knights betrayed by the church, sent on crusades to die, and know hiding in the shadows using arcane knowledge to battle monsters. Did I mention that some of them have special Dracheneisen (Dragon Iron) swords that kill the hell out of monsters? Seriously, someone besides me is trying to squeeze The Witcher into this game.

- Explorer’s Society – Are archaeologists in the Indiana Jones style, looking for ruins (Syrneth & otherwise).

- The Invisible College – The church used to be a huge booster of science until the inquisition took over and declared it the end of history. As such, science has largely gone underground.

- Knights of the Rose & Cross – not secret at all, they’re a very public order of heroic do-gooders. Because this is swashbuckling, I am actually saying this with no irony whatsoever.

- Las Vagabundos – The Original El Vagabundo was a masked hero who saved the king of Castille from assassins and did the Zorro thing across Castille. Over time, the masked hero has shown up to save many heroic leaders across Theah, shading some Scarlet Pimpernel into the Zorro mix. There is more than one El Vagabundo, but how many and who they are (and who helps them) remains a well kept secret. Notably, there are 5 “real” Vagabundo masks, which are artifacts of badassery, and for 10 favor, you may don the mask.

- Močiutės Skara – Which I will just call Skara because I’m a dumb American, is for all intents and purposes The Red Cross. They are, in fact, so good and reasonable they I assume their splat will reveal that they’re actually plague spreading supervillains.

- Rilliscaire are Anarchists crossbred with hipster Malkavians. If Neal Stephenson wrote a 7th Sea book, his protagonist would fall in with these guys so they could explain “mimeme warfare” to him.

- Sophia’s Daughters are a Rilliscare branch with the much more practical goal of “teach women to read, and smuggle fate witches out of Vodacce, where they’re effectively property.” They’re pretty awesome.

What Has Changed

- Die Kreutzritter and The Daughters of Sophia both look like their original form, not their super-secret-everything-is-a-lie form, so I am hopeful. DK in particular seem cool without needing any extras now.

- Los Vagos, now Los Vagabundos, have gone international with an agenda of protecting heroic rulers. I must add that I am very pleased that mask is in play from the outset.

Game Master

So, this is the advice section. I’m feeling cautious about how to approach this because the last thing I want to do it get into a point-counterpoint with some very sincere GM advice.

If you’re familiar with Wick’s other work (especially Play Dirty), then this will, if anything, feel kind of toned down. But it’s a useful read. There’s a little rule Zero/rulings not rules stuff and a brief explanation of spotlight, but the real meat starts when it offers GMs advice under the auspices of their three different roles – Author, Referee and Storyteller.

The Author need to have agendas and voice, to have a sense of genres (with a nice genre breakdown that is curiously missing Romance). It also provides a dozen “dramatic situations” as plot seeds and talks about act structure, building a story and the importance of improvisation. Were I to summarize, I would say it encourages doing all the work necessary to support an entire railway network, but then remove the tracks – prepare, but do not expect.

The Referee hat is where we get the big ruling, not rules rant, so there’s that. It boils the rules down to:

- You create a Scene.

- Players create Raises.

- Players use Raises to change the Scene.

Which is accurate, for good and ill.

There is then a discussion of consequences which is well worth the read. In essence, because death is not much of a threat in this game, players should feel more liberated to take risks, but GMs need to learn to create consequences without the threat of Zero HP, and it talks about how to do it. Super good stuff, and useful in any game.

Similarly, a discussion of pacing is very welcome. It’s a critical topic that tends to not get enough coverage.

The Storyeteller role is about techniques. The 5 questions (who, what etc,), 5 senses and the 5 voices (action, description, dialogue, exposition, thought) offers a nice trifecta of practical advice. There’s also some guidance on playing memorable NPCs

After that is a nicely structured section for what to do after the game, with guidance for how to do a solid retrospective, including the familiar “What did you like most? What would you have changed?”. This is good practice, and it’s nice to see it explicitly laid out.

Last is four pages on creating compelling villains, and it’s a delight.

And with that, we get to the end, and the terrible, terrible index. Really, it hurts my heart. Also, there’s a chart with all the advantages and their costs, followed by a character sheet which is pretty bland, except for having a very lovely death spiral.

Thoughts that did not fit anywhere else

- It is jarring when the book calls out something as “nope, this is explicitly not allowed”, especially when that something is awesome-but-in-conflict-with-the-setting-as-written. For example, the only way to get a Dracheneisen weapon is through Die Kreutzritter, and my response to that is a rude, wet noise.

- The basic math here is that two dice roughly equal one raise. One hero point, by itself, is worth one die, so most abilities that let you spend HP to generate extra raises are pretty sweet.

- Guns have a gimmick – if someone shoots you, in addition to whatever it does, it also inflicts a dramatic wound. That’s fairly nasty, though mostly only useful against heroes and villains.

- This is a John Wick joint, and it shows. A huge amount of the game could be summed up as “This will be awesome. Yes, your GM could totally screw you over, but just trust her, she won’t” and you are either comfortable with that or you’re not.

- Super trivial thing, but one piece of advice in the game is that if players get a cash reward, give it to them at the beginning of the next session, not the end of this one. Very good idea.

- Zero mention of the Bargainers, or even any vague references to them. Genuinely wondering if that element has just been removed or transformed.

- I was SO HAPPY there was no pistol school among the swordsman schools. That damn near destroyed 1e for me.

- I am a little worried about the efficacy of swordsmen over everyone else. I’m willing to see some other builds in action, but at first glance, swordsmen seem nearly overwhelmingly badass. Of course, if that does turn out to be the case, then I will shrug, and make the first one free for everyone.

- It utterly kills me that there is no timeline anywhere in the book. A lot of stuff has happened that gets referenced, but I have zero context for when it was or how long it lasted.

- There’s a weird mechanic of using the current number of raises as a countdown. It feels a little awkward and I am already thinking of situations where it’s going to be a problem. Similarly, there are a few abilities that tweak initiative order (letting you act as if you had more or fewer raises) and they make me nervous – if I was going to break the system, that looks like an excellent point to exploit.

- There are a number of advantages that are effectively “Spend a hero point to make something happen”. They’re VERY powerful, so it’s important to note they only work on other heroes if the other hero agrees (and also receives the hero point). There are still things to be careful about, but that removes the most obvious abuse.

- As a table, it will be important to decide what it means for somethign to be a story. I might say, for example, that if it could be handled offscreen, or with a single roll, that probably doesn’t qualify, but there’s an implicit statement of taste in there. Another table might allow coffee shop stories (character-centric stories with no real conflict, just conversation that explores and highlights the character). Worth making sure everyone is on the same page.

- So, the pacing difference between a task and a sequence really boils down to this: in a Task, you distribute your raises and move to an outcome; in a Sequence, you spend your raises one at a time because the situation may change each “round”. This makes sequences more dynamic, but it’s reliant on there being a source of competing raises (a villain). I need to test this as the table, but I feel like I want some tool to find a middle ground, so there can be dynamic scenes without a villain present.

- This is a very generic system at its heart (albeit a strongly opinionated one). It is tied to Theah primarily by sorcery and the specific advantages. It’s tied to swashbuckling mostly by strong authorial intent and a few rules synergies. It would not be hard to tweak this to a wide variety of games. Whether that’s a bug or a feature is probably a matter of taste. I lean towards feature – 7th Sea embraces a very broad view of swashbuckling, so it’s necessary to have a system with a lot of stretch.

- edit: I forgot to explain how rank 4 in a skill helps you build better sets. In a nutshell, you get the option of building 2 raises out of a 15 (in addition to 1 raise from a 10), which is pretty cool.

And in Conclusion

I am leery. I am leery of a new generation of splatbooks with crappy twists. I am leery of the too-open system of raises turning into a mechanical exercise. I am leery of Metaplot.

But I am also excited. I am excited about character stories. I am excited to take the risks system for a spin. I am excited by the new map and the slightly more logical world. I am excited to kill monsters with a goddamned dracheneisen sword.

Even if it all crashes and burns, I’m glad I got this game and backed the kickstarter. Like its predecessor, it’s full of great parts which I will steal liberally (the original 7th Sea provided the major inspiration for Aspects). But hopefully it won’t crash and burn. I intend to play, hopefully soon, and see what this puppy can do.