An interesting thing about Blades in the Dark score planning is that it’s so loose that it relies heavily on shared understanding at the table to build a framework. This works fantastically well for clearly defined tasks like stealing an object, killing a target or even smuggling goods past a blockade.

An interesting thing about Blades in the Dark score planning is that it’s so loose that it relies heavily on shared understanding at the table to build a framework. This works fantastically well for clearly defined tasks like stealing an object, killing a target or even smuggling goods past a blockade.

Where it gets a little bit trickier is for that most classic of scores: The Con.

It can feel a lot more complicated to try to run a con, because the action of a con is often indirect, and while groups who are comfortable tying together a meta-narrative can kind of fake it but tying together unrelated events at the end, that’s a bit of a kludge. It’s a way to work around the fact that we can clearly imagine the flow of action and consequence in a heist in ways that we have a hard time doing with a con.

My sense is that this is largely a result of imagining the con to be more complicated than it really is (structurally). It is my hope that if we can demystify the structure of a con, we can make it a little bit easier to run a score.

Two caveats on this advice. First, I’m approaching this through the lens of Blades in the Dark, so while this may be applicable in other games, I’m not setting out to solve those problems. Second, this is a simplification, and just as with any other score, the differences are in the details, and they matter a lot.

So with that out of the way, let’s look at the con. But perhaps in a roundabout way.

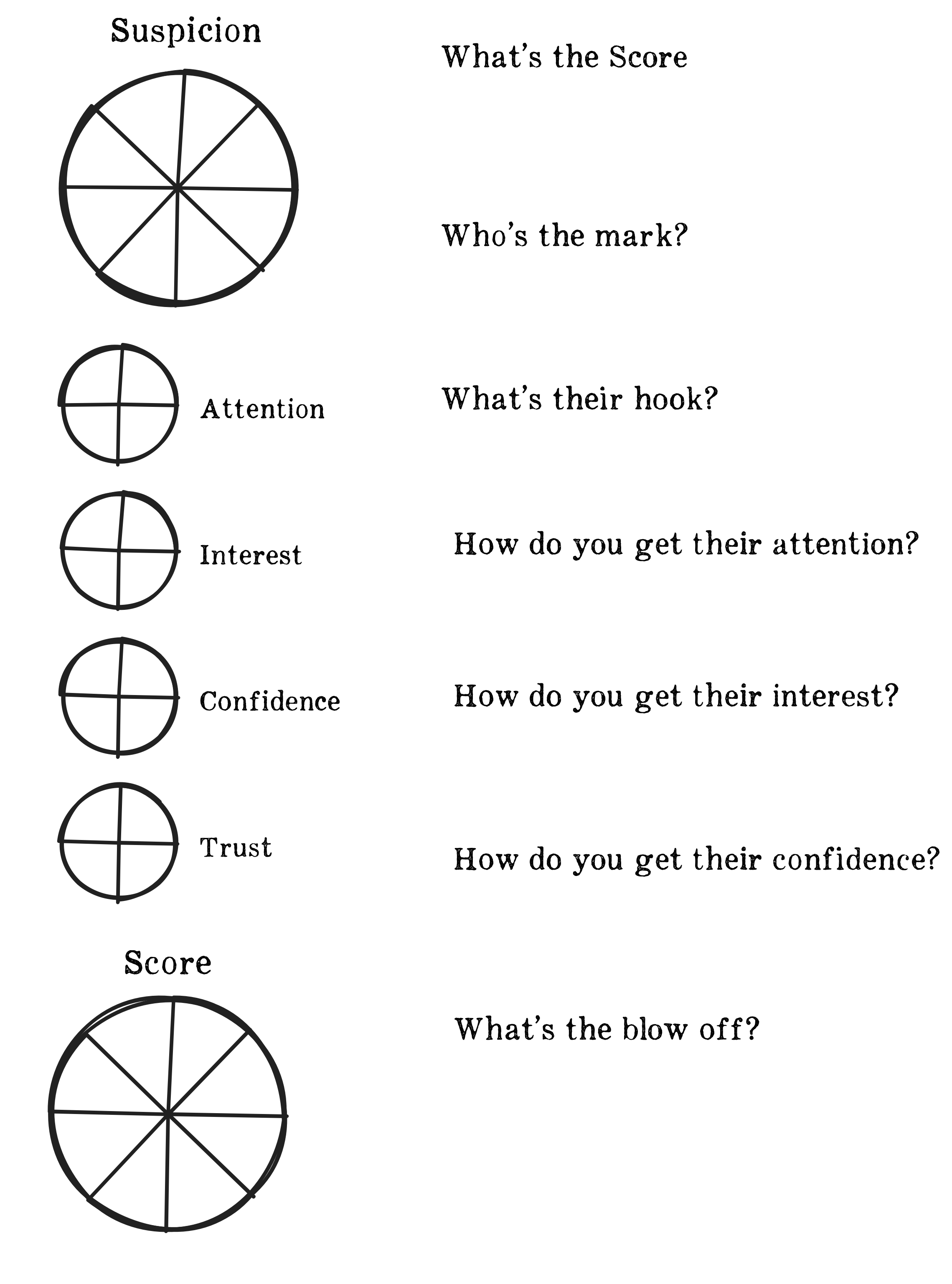

Every score has a keystone action and supporting actions. The keystone actions is the purpose of the score. In a theft, it’s stealing the item. In an assassination, it’s the murder. In a smuggling run, it’s the delivery of the goods. Supporting actions are all the actions required to get to the keystone, and possibly to get back out. We get this pretty intuitively for things like left: guards must be evaded, locks picked, alarms disarmed, escape routes secured and so on.

Where we run into problems applying the model to cons is, I think, I misunderstanding of what the keystone action of a con is. Most commonly, we think the keystone action of a con is tricking someone, but that doesn’t work.

Instead, the keystone action of a con is this: You make someone do something.

It’s possible that sounds too simple, so let me unpack a little bit. “Do something” can be incredibly varied, though it’s usually “give me something valuable” (like money or a secret journal or the like) or something one step removed from that (like entering a password in a compromised system). Other good somethings include “do something incriminating”, “attack the wrong person” or “insult someone powerful” but it can be really anything.

Just as with theft, this keystone action is tied to the crew’s goal, and just as with theft, you can build the whole score around it. But there’s a twist (it’s a con – there’s always a twist) in that the purpose of the con usually serves another purpose. That is, if our crew knows we want to steal from Karl Snaggletooth, that is not enough information – we need to decide what action we want someone to take. And it might be as simple as “Karl hands us 100 Coin” but it’s usually a little bit more complicated or specific. This is why, in fiction, one part of the score is figuring out what the con is going to be.

That process is fun for some, not for others, so for purposes of Blades, we’ll want to skip over the process of figuring it out, and assume that the crew know what the goal of the con is. From there, is it a matter of working backwards by cycling through two questions:

- Under what circumstances would that happen?

- How do we emulate those circumstances?

Now, the simplest possible con is the sob story. I want you to give me money, you would do that if you think I deserve it, so I tell you a convincing sad story and voila, I walk away with your money in my pocket. This is to a con what shoplifting is to a theft – the simplest example of the form.

But as with a theft, simplest doesn’t cut it off fun play. A more entertaining con is built upon a sequence of deceptions to create a specific effect. At the end, I’ll run through an example of how just a pass or two through that filter should be enough to get you what you need. But before that, let’s go to the bullet points.

Things to consider when you plan a con:

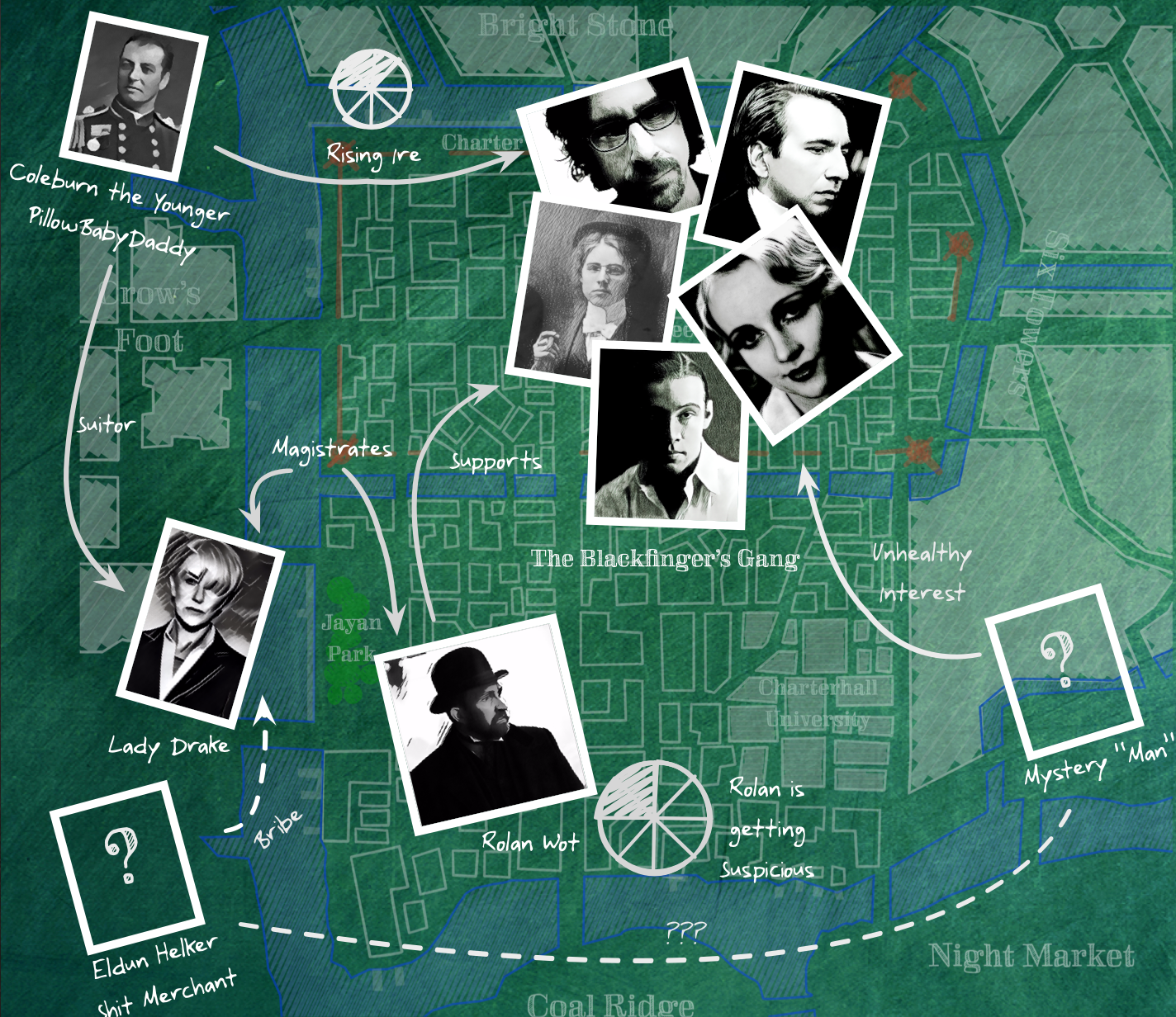

- Cons are better done in teams, partly because it is easy to be suspicious of one person, but harder to be suspicious of multiple people, especially when they are “strangers”.

- One of the tension points/things that can go wrong during a con is a shortage in the roster. If a member of the crew gets made, then they can’t also play a role in the con, which can be a problem if the role is necessary for the plan. Forcing characters into unfamiliar roles, or relying on NPCs to fill gaps are great consequences and complications.

- While it is not strictly true that you can’t con an honest man, it is definitely a lot harder to do so for substantial amounts of cash. A con depends on the mark’s motivations, and self-interest and greed ad much more controllable motivations than charity or goodwill towards man.

- Specifically, almost every good con hinges on convincing the mark that they are getting away with something and profiting from it. Exactly how that convincing is done depends on the mark, but if they’ve got something worth stealing, then odds are good they probably think they deserve more, and are confident they’re smarter than those who have less. That’s the hook.

- It is easy to focus on all the film flam that leads up to the con, but don’t be distracted – the thing that separates the amateurs from the pros is the blow off. The blow off is how the con ends and it needs to serve multiple purposes.

- It needs to make sure that the prize is in the crew’s hands without appearing to be

- It needs to leave the mark with no reason to follow up, come back to or re-examine what happened. Ideally, the mark feels indebted to the crew.

- That second point is critical – at the end of a good con, the mark might be upset about things that went wrong, but he should bear no ill will towards the crew. Either he should think warmly of them, or he should never think of them again (because he thinks they’re all dead).

- In game terms, a really good blow off should be able to drastically reduce the potential heat from a job.

- In Duskvol specifically, you want a friendly blowoff. The city is not so big that you can be guaranteed to avoid the mark forever, and you don’t have a lot of other places to go to avoid them.

- Greed will kill you. At some point the mark will test to see if he’s being conned, and he’ll probably do this by creating an opportunity for fast profit, on the idea that criminals would take it. And dumb ones will. If a golden opportunity presents itself, consider the possibility that it’s you who are getting played.

- Roles are a critical part of the con. They may be fully fleshed out, well documented aliases, or it might just be a particular kind of stage character you excel at (the Severosi with a limp) depending on what the con needs (because, if nothing else, using your real name on a con is a bad mistake).

- A role is an asset and can be created in downtime. For a PC, the role includes a name and enough details to comfortably pass as the role under most circumstances. For a group, roles are nameless, but fulfill a type. Creating a role allows a lot of fiddly bits of planning to be folded into a single action. The main advantage of a role is that so long as you play to it, it requires no additional effort to deceive or fool someone. However, roles are fragile, and won’t fool anyone who knows you or sees countervailing evidence. A compromised role is destroyed immediately.

An Incomplete List of jobs in a Con :

- The mark – the person being conned

- The grifter, aka the con man, sometimes aka the face is the person running the con. If they’re running the con on their own, they pick up all necessary roles. Ideally, they should not be the first point of contact with the Mark – that’s the job of the roper.

- The roper is the person who pulls the mark into the con in the first place, usually by making the mark the “winner” of a smaller scam. A rookie mistake is to expect the roper to be the one who runs the con, but in a good con, the roper is the one who introduces the mark to the real con (often over their apparent objection) and at some point the mark will throw the roper under the bus (metaphorically, we hope) in order to get closer to the true con.

- The shill exists to validate the con. They are the person who is ready to pounce on the opportunity that the mark is being offered, and may actually object to the Mark’s presence. The Shill reinforced the value of the scam while also giving someone for the mark to beat.

- The false mark doesn’t show up in every con, but is a useful role for snagging a certain kind of Mark, particularly the kind who think themselves very smart (which is most of them). The false mark is the target of the fake con which the real mark is getting drawn into.

- Extras fill out a scene. In a good con, there are no random strangers or opportunities for contact that are outside of the control of the crew, and there’s an entirely category of criminals/actors who fill out these scenes.

- The fixer has no role in the con itself, but is instead something more of a stage manager for it. They keep track of what’s going on, oversee communication and – critically – step in when things go wrong.

- The outside player has no role in the con until the very end, where they enter as part of the blowoff. The royal agents whose investigations scuttle the whole thing? Hopefully that’s the outside player.

- There are a lot more terms, but that should be enough for you to figure out things for your players to do.

In Blades, every crew member is assumed to have competence in thinly skills, including the con, and one useful thing about the various roles of the con is that they provide different jobs for characters with differing skills. Yes, someone (usually the grifter, sometimes the roper) will need strong active deception skills, but a good crew makes roles that line up with who is available. If your cutter is a terrifying veteran, then the role he plays should be a terrifying veteran. Not only does that make the deception more persuasive (because it’s mostly made of truth) it helps give a role to every player

—

To tie it all together, Let’s use the classic example, familiar to fans of The Sting – the wire scam. The con is to convince the mark to hand over a giant pile of money by convincing him to bet on a game that he thinks is secretly rigged. Note that we now have an answer to wonder what circumstances the mark would give up money, so now we come to the question of how to emulate that. Well, we need to get him into our fixed betting parlor of course, and we need him to believe that the fix is legit.

Now we have action. We need to set up the fake parlor, we need to rope him into it, and we need him to believe it’s a sure thing. Some of that we can do right away, but how do we get him into our gambling parlor?

Well, that’s another con. A smaller one. We find someone who owes him money (or maybe borrow some money then wait till the threats come) and then suddenly pay back all debts and interest. Our mark’s a clever man – the payback is fine, but he’s going to be really interested in how this guy (our roper) suddenly has money. He’s going to find out about this betting parlor, and he won’t take no for an answer.

Notice something here: The mark is operating under a sense of false proactivity. If we sent in the roper to tell him about the gambling parlor, he’d be suspicious as hell. But since we sent the roper in to not tell him about it, he is going to trust any data he extracts because it comes from him.

Once we’ve got the hook in, the roper introduces him to grifter, who doesn’t want another partner, so the mark is going to have to force the grifter to accept him (further reinforcing the mark’s belief that he is in control). Once that happens, the mark sees some wins, but they’re small – frustratingly so. The opportunity for a huge score is obvious, but small timer’s like the roper don’t see it.

But the big score requires a big bet, so the mark needs to put up some money to match the (bogus) amount the grifter is putting forward. Everything is going great until the bluecoats raid the place and take everything. The mark is nearly arrested, but escapes thanks to the help of the grifter. In the end, both have lost it all, but the mark is grateful, and they go their separate ways.

But, of course, that was the blowoff. The bluecoats were fake, lead by the outside player, and the mark’s money is safely in the hands of the crew, while the mark is going on his way convinced that the grifter is a stand up citizen.