On a very primal level, one of my favorite things about the various Powered by the Apocalypse games is that they use 2d6 for resolution. It’s just about the simplest possible way to generate a curve, using the most ubiquitously available dice. The math is easy and fast. It uses an even number of dice, which may seem like a small thing, but is important when you want to buy cool dice (you don’t want to know how much I paid for the metal set I picked up at Gencon).

But PBTA was far from the first 2d6 system, and and I can’t think of another such system that has been so sticky. A big part of that is, I think, that PBTA has driven forth a very concrete means of reading the dice that only generates 3 outcomes1 with very little player training. Once the player has internalized that 7-9 is the middle result, they can easily infer whether they’be done better or worse.

There’s some interesting knock-on effects to this. First, it rewards the simplicity of the dice. It would be easy to produce a more nuanced curve with more or different dice, but that could impede the ease of learning that core number. It would also introduce a temptation to get fiddle, which would also detract from the simplicity.

It also allows for the designer to play GM in a very concrete way. The design of a move is a decision bout how an activity should look – that’s one of its big strengths. It’s apparently simple design actually conceals something a little more complicated. I’ve talked about this before, but the most direct way this is expressed is the range of outcomes. Consider:

10+ Success with Benefit

7-9 Success

6- Complication

Vs.

10+ Success

7-9 Success with Complication

6- Problem

Vs.

10+ Success with Complication

7-9 Not Quite Failure

6- Ha ha ha ha ha

As you look through PBTA material, you can find all three of these patterns (and others) reflecting the designer’s take on that particular sort of action in the context of the genre. Sometimes this is applied with grace and nuance, sometimes it’s shotgunned across things as an expression of the designer’s taste. Which is fine – PBTA is an opinionated game system, so this is a feature.

But, of course, it makes me go hmm.

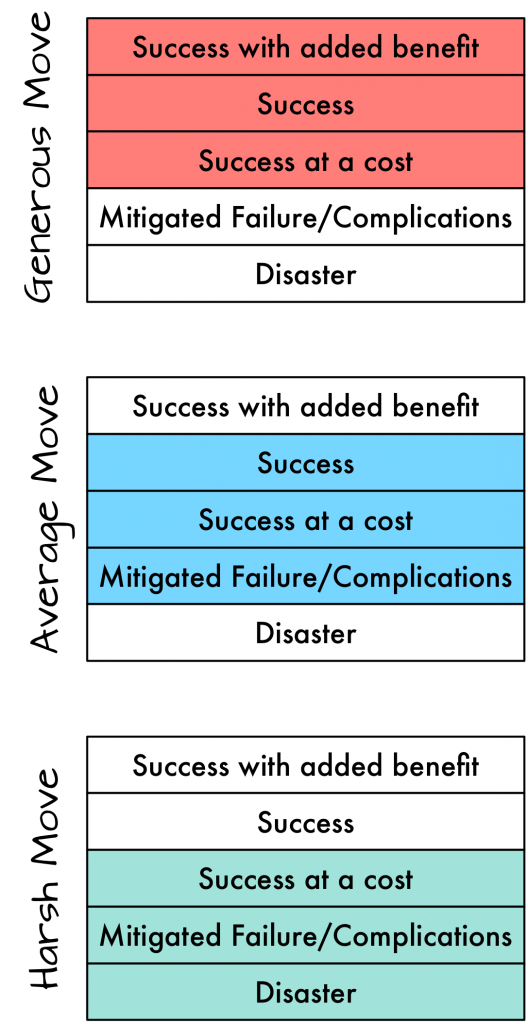

If one wanted to start from the core idea (a simply expressed narrow range of outcomes) it would probably be possible to create an ur-list of maybe 5 outcomes. You could theoretically produce three sets of moves out of it (high, medium, low) out of that set. So, suppose the list is:

So a “nice” move would be

10+ Success with Added benefit

7-9 Success

6- Success at a cost

And an average move would be

10+ Success

7-9 Success at a cost

6- Mitigated Failure/Complications

while an “unkind” move would be

10+ Success at a cost

7-9 Mitigated Failure/Complications

6- Disaster

Such an approach would not need to replace any existing moves so much as simply provide a set of guidelines for whipping up moves on the fly. And that works on paper, but it has one big drawback – it is effectively a back donor for inserting difficulty into PBTA and that is probably a very bad thing indeed.

So I’m not so sure there’s much use for this idea in the context of PBTA as anything but a shiny bauble. However, as an indicator for how to maybe steal a chunk of PBTA tech and use it elsewhere, this may prove a very interesting starting point.

- Yes, there are ultra-positive results in some builds, but they are something of a sidebar. ↩︎