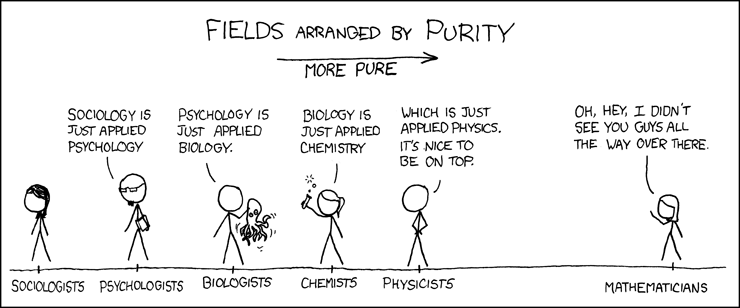

I enjoy the webcomic xkcd, but it occasionally gets on my nerves with its nerd one-upmanship. This is not a huge deal because, hey, it’s a nerd comic, you need to expect a certain amount of that. But there was a math uber alles one that sort of stuck in my craw for a while which I’ve now found peace with.

See, the bit I’d never realized[1] (and which I don’t know if even the author has thought about) is that there’s something not shown here, something which is only implied but which puts this in context. There’s one other person here, one we’re not seeing a little stick figure of, and that’s the storyteller. That may seem a hokey term, so feel free to swap in writer or artist or whatever you like, but I’ll stick with storyteller because I think that speaks to the heart of it: someone took this stuff, and made it say something.

See, the bit I’d never realized[1] (and which I don’t know if even the author has thought about) is that there’s something not shown here, something which is only implied but which puts this in context. There’s one other person here, one we’re not seeing a little stick figure of, and that’s the storyteller. That may seem a hokey term, so feel free to swap in writer or artist or whatever you like, but I’ll stick with storyteller because I think that speaks to the heart of it: someone took this stuff, and made it say something.

None of this is meant as a sleight against any particular field. Storytelling is as much a part of math as it is cooking, politics or any other endeavor. None of them work without creating stories. Once you get past the abstracts and start talking about how an individual person understands things, that understanding takes the form of stories. Cause an effect is a story. The process for making things is a story. These stories may be boring or short, and they may violate every dramatic rule that we like to apply to fiction, but whatever form they take, they’re how we see the world because we cannot actually perceive truth.[2]

Marketers, politicians and people in power know this, and have for a good long time. When you hear someone talking about spin or controlling the narrative, they’re talking about the importance of stories. They’re looking at a pile of stuff and trying to figure out how to turn it into a story that is compelling enough for people to buy into yet which serves their interests. Other people will look at the stuff and create different stories. Once these stories are out in the wild, they’ll fight among themselves until one becomes ‘true’. Even if some people still seek to look at the stuff, for most people the story is all that’s going to matter.

There are examples of this everywhere. Literally, everywhere. Get up, walk around and look at a dozen things and tell yourself about them. Look at what you tell yourself, and stop and consider how much of that is a story. And here we come to the tough part.

As overwhelmingly powerful as this idea is, its a very difficult one to discuss in the wild. While almost anything can be used as evidence of it, actually doing so is going to risk the wrath of people who have bought that particular story.[3] The topic then becomes about the particular story rather than stories in general, and that’s useless. So I’m going to risk it here, but be warned that I don’t care much about the specific stories except as illustration.

As I write this, there’s a bunch of oil spilling out of a pipe from an exploded oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico. While people are rushing to deal with the physical problems this represents, there is currently a kung-fu fight of epic proportions over the narrative of what all this means. BP, the company leasing the rig and the public face on this, wants the narrative to be about how responsive they’ve been and how they’ve kept this under control. Proponents of offshore drilling want to come up with a story that acknowledges this as bad but not something to reflect on offshore drilling in general. Opponents of offshore drilling want this story to be apocalyptic.

None of this even touches on smaller stories, like whose fault it is, or whether liberal commandos blew it up to discredit Obama’s opening of offshore drilling.[4] Look at the responses from the gulf Governors, most of which are prepared for disaster, one of which is insisting nothing’s wrong. Neither group can say they know what will happen, but each is positioning itself for the story they think is coming.

That’s the real trick. You never can see the story mid-stream: story is only created after the fact. But it doesn’t just happen – or rather, it doesn’t just happen unless no one steps up. Stories are a lot like wet cement. While the events are happening, they’re fluid and manipulable, but as time goes on and the story starts becoming more established, it gets harder and harder to change. For all the weaknesses of a 24 hour news cycle, the one strength is that we get to see the cement before it hardens, which means that the ultimate story can be created by anyone who can build something compelling enough.

As proof of this, look at the recent financial crisis. There has not been any single story more important than This American Life’s Giant Pool of Money. Even if you haven’t heard it, the people you’ve listened to have, and their stories have been shaped by it. This is not because it introduced new information, because NPR[5] has some special insight or because it shocked us in some way. It’s because they told the story of the financial crisis so well that it could not be ignored.

And this is where I come back to gaming. If you game (or write, or create) then you live in the world of stories every day. Some people characterize that as escapist, but I like to think of it as boot camp for the real world. And by the real world, I mean the world of stories.

Power, influence and change have always come from stories, whether it was the story of the divine right of kings or the story of the founding fathers. Historically, those stories have been in the hands of only a few people, transmitted slowly and changing rarely. By the time they got to anyone else, they had already been told. Most people’s stories were about getting them through the next week or next winter, and on those occasions when they were in a position to see these other stories, they were rarely in a position to change them, save under the most dramatic of circumstances.

But that’s changed. If you’re reading this, you’re in a position to take advantage of that change. Stories travel fast now, reaching us before they’ve fully formed, and all the stories of the past are spread out before us, awaiting a critical eye. For better or for worse, the firmer your grasp on stories, the more you can do. This is not merely for novelists or screenwriters, it’s something that can matter in every conversation and blog post, or even around your office. If you can see the world of stories, know the story you tell when you do everything from buy cereal to go to college, you can make a difference.

There’s a cynical instinct to suggest that this is all about appearances, but that misses the key point, a point that makes gamers uniquely equipped to face this new reality. See, this is not about YOUR story, it’s about everyone else’s story. The story you tell yourself is compelling only to you. If you want your story to really work, it needs to be compelling for other people. You need to see the story they see.

So with all this in mind, a hobby that is all about extracting story from events and shifting perspective from yourself to someone else sounds like exactly the kind of training one might want to have.

1 – Other than the fact that Liberal Arts continue to get a bad rap

2 – If the instinctive response to this is that Math Is Truth, then we have a disconnect that’s not worth arguing about. Really, that’s true of any X Is Truth response, but mathematicians and fundamentalists are usually the only ones you really have to worry about it from.

3 – And I note, we ALL buy into stories – we need to, otherwise we become paralyzed an incapable of doing anything. The fact that someone has bought into a story does not make them irrational or unreasonable.

4 – Yes, it’s been proposed, and it’s a great illustration of something important. The fact that a story is crazy doesn’t necessarily make it a bad story. Stuff like this can be sticky.

5 – Radio is an underestimated medium, whatever your political party. It is easy to dismiss NPR or conservative talk radio (especially whichever group you disagree with) but radio is such a limited medium that it demands the mastery of stories because it can’t compensate for their absence with sleight of hand. Successful radio personalities craft compelling narratives; that’s what makes them successful. Even if you don’t like their stories (or if you conflate their stories with truth), they’re worth paying attention to if you want to see how they do it.

Before I begin I’d just like to make two statements. Firstly the gap between the physicist and the mathematician is intentional, primarily to stop the distraught mathematician from throttling the physicist for abusing his art (and make no mistake that true mathematics* is a self-contained art which has no relation to the outside world except it has**). Secondly, as Ernst Rutherford was wont to say, “all science is either physics or stamp-collecting.”

…someone took this stuff and made it say something.

And it is here where I think you have the wrong idea about the purpose of science. Because science doesn’t say anything. It’s a technique, a method, for creating a model of the universe

…we cannot actually perceive truth.

I think Neils Bohr said it best.

“The opposite of a true statement is a false statement, but the opposite of a Profound Truth may well be another Profound Truth.”

The advantage that physicists and engineers have is that we have to operate in the real world. We have an objective test of the truth of the matter. If we build a bridge and it falls down, then it obviously incorporated some falsehood into its construction. Similarly, in more esoteric fields, we rely on observational data to confirm our theories. If we can’t get that data, we look for new theories or methods of confirmation. If we get contradictory data we discard the theory.

You can tell any stories you want about that bridge (or underwater drilling operation), but that won’t change the fact that the bridge fell down (or the oil well broke open).

Of course, you can spin the interpretation of the model so as to disguise the exact nature of the reason why the bridge incorporated a falsehood anyway (the geologists didn’t realise the footings were undermined by an aquifer), but that doesn’t alter the fundamental approach that model was wrong and the bridge fell down.

The universe plays short shift with equivocation.

[* And mathematics is very dirty itself, since philosophy exists to right of it. If you doubt me, ask a mathematician to express the platonic form of a sphere. She will. Then ask her to do it again in polar coordinates (or cartesian if she did it the simple way first). Two representations? Obviously not platonic then. To paraphrase a parable from Isaac Asimov, you can rate the purity of the subject by the size of the wastebasket that it needs. Does that save Liberal Arts?

[** Although one can also make the case that physics has no relationship to the real world either, because the goal of physics is to create a model of the universe (from which it is possible to explain and predict what is happening), not to actually explain or predict what is happening. The difference is subtle, but often lost on non-scientists (and many scientists who haven;t taken a look into the philosophy of science, I’m afraid).]

The wiggly bit here is that I don’t think that gaming *necessarily* provides the training for good storytelling. There are plenty of let-me-tell-you-about-my-character folks out there who can’t, say, tell an INTERESTING story about their characters.

So how do you build that?

@rev My response is already in your comment:

a method, for creating a model of the universe.

Stories are models. Specifically, they’re models that our squishy, meaty brains can understand. I by no means wish to diminish the concrete benefits of the sciences – I like my antibiotics and air conditioning, thank you very much – but I want to call out that the intangibility of human interaction requires a different mode of thought.

That is to say, a bridge is concrete and measurable, and that reality makes it important. The reasons someone chooses McDonalds over the Democratic party or whatever is, in contrast, almost entirely ephemeral, and by the yardstick that we use to judge the bridge, it doesn’t matter.

But the trick of it is that, in the actually day to day business of life, perceptions and stories and ideas and impressions matter a LOT. They matter enough that Liberal arts have been trying for decades to express them in terms of the hard sciences[1] to middling success. I suggest the real trick is off on another tangent entirely.

1 – Of course, the real culprit for this is the Cold War, especially JFK. The space race and other contests made huge amounts of money available for scientific pursuits, so suddenly all the philosophers and writers had bigtime to find a way to couch their work in more scientific terms. Yes, the idea of social sciences is older than that, but money changes everything

@Fred That is, I admit, the million dollar question. The tools are all there, but getting people to pick them up….

Storytelling is as much a part of math as it is cooking, politics or any other endeavor. None of them work without creating stories.

Quoted for truth.

And yes, this is absolutely true in science, as well. We study things because they are important to us. We want to understand the things we study; we want to learn their story.

On the nature of storytelling and narrative, there is an aside I would like to relate.

By age 3, children have a significant control of their native language. On the other hand, people seldom remember much of their lives before age 6 or so. One language theory posits that is because that age area is when we start /narrating/ our lives instead of simply speaking; we add meaning to the events instead of simply relating them. Something about the story-ness makes it stick.

Events which we have strong narrative about — painful, pleasant, or any mixture — stick with us for much of our lives, and it appears what sticks is the “story”, especially with those cases where the “story” and “facts” have diverged.

Thus, it appears all humans are inborn narrators, though sharing a well-crafted story remains art.

Some folks have suggested that storytelling was an evolutionary advantage. Tell good stories, get good mates.

Whilst a story is a model, consistent in and of itself (at least with the good ones), it is a construct that cannot effectively be tested.* In science it is not the construction of the model that is important, but the testing of it. And that is something which escapes a lot of people (especially including a lot of my students).

Which is a lot of the subtext of the cartoon. At least that is my opinion and I’m sticking to it.

Which is not to dismiss the power of storytelling in any way. It is very powerful, and a skill that has been largely forgotten (or rather debased heavily). Especially the art and tradition of oral storytelling, which, like, live theatre, requires the orator to interact with the audience.

And roleplaying is an arena where it is possible to train storytellers successfully, but like all arenas it can be a bloody and messy affair. And the usual victors are the gladiators who have been trained in the ludus, rather than the prisoners with the wooden swords.

Personally I find the role-playing group to be much more akin to the theatre, with the actors being their own audience. The job of the gamemaster is more akin to that of the stage director, making sure the actors hit their blocks correctly. A good actor can raise the quality of the ensemble by playing to them, supporting them, and extolling the best from them, even if it just by example. And when the script is weak the actor can improvise successfully [or just give up an collect their paycheck.]

But this is the art of oratory*** rather than storytelling. The ability to deliver the message rather than craft it. To convince us of the truth of story. It is a trick best learned from the great orators of history, the ability to create a flow of word which capture the spirit and mood of the listener.

This resonance with the audience, where the audience identifies with the story and feeds back into the telling, is where a mere story becomes a myth, a legend, a force that can move mountains.****

Of course, having a good script to work from does help.

PS: On a related note enjoy the following songs from Tripod vs the Dragon (also referred to as it was being written as Dungeons & Dragons The Musical). In particular, the song Bard which is relevant to this discussion (but don’t ignore Ivory Tower!).

[* One could argue that the test of a story is handled in a different way, but any truth in the story then becomes subjective. In which case, is it true any more, or just another falsehood.** The ability of the storyteller is to convince us, the listener, that the story is the truth, if only for a little while.]

[** The reverse argument can also be made (especially by a physicist

[*** Interestingly in Republican Rome the mouth was sacred because the oral tradition was the basis of law. Court was a matter of successful oration (and the support of followers to support you or shout down opponents). Which leads to the interesting idea that actors and prostitutes were infame (those who had lost their civil rights) because they debased their mouths, each in their own way.]

[**** And role-playing is a good place to develop this interactivity. The best games have the players invested in them. Consider the game sessions you remember best.]

Rev,

In science it is not the construction of the model that is important, but the testing of it.

Everything in this process that is important is connected to a narrative.

Why are we studying this? What’s the history behind it? What is the story of the model? How do we make sense of the results? Why do we care if we use scientific methodology at all?

Don’t get me wrong. I’m a big, big fan of the scientific method. But every scientific test has a real, human person conducting it. Someone with a brain that looks for answers, sees patterns, and tells stories.

Liberal Arts have no place in the cartoon because they aren’t a field of science to begin with. Granted, math isn’t science either, but many people don’t realise that.

And your point, while interesting, doesn’t concern the subject you started talking about, which is science and math. It may have some place in actual sciences, who do concern themselves directly with the real world (though rev brought up an interesting point about physics), and thus you can at least put meaning to everything, and there’s more place to argue about things.

In math, there’s no connection to anything (at least, there needn’t be), it’s just there. You don’t need a story when discussing a polynomial or a derivative or a quotient of a free group. It’s just there, and our mind can understand it nicely enough. I’m not trying to say “math is the Truth”, since Truth is a big word that doesn’t mean much. I’m just saying that we CAN understand math without a need for any other story or opinion, because there’s very little place for opinions in math – unless you talk about personal preferences or get into weird philosophy (such as “imaginary numbers don’t exist and it’s wrong to use them!”).

People who look at math from the outside enjoy attaching stories to stuff (such as “what is the profound meaning of Godel’s incompleteness theorem”). While mathematicians just shrug and say “there’s no profound meaning, it’s just there for what it is”. Meanings are the business of physicists. We’re just toying around with abstract constructs.

I’m only talking about math here since that’s what I know myself. I won’t argue that actual sciences necessarily need stories. Although, in science you can actually have camps who believe different things – something that has no real place in modern math.

So, I’m not dismissing what you’re saying – it’s largely correct for our daily lives and events that concern it. I’m just saying that our mind is capable of enough abstract thought to allow us to think without the framework of story, meaning, events and consequences.

Math is, as Barbie once said, hard. Or at least it is for people like me, who have brains engineered for something else.

I like how the folks harping on the only cosmetically relevant statements about math and physics in this post are shoring up Rob’s more relevant point that you can’t really discuss what he’s talking about without people getting distracted by the specifics of the example instead of the principle. Well done!

@Fred: Thanks! Glad to be of service!

Oh, and I shall leave you with this deeply philosophical question: “Would you want to live in a world ruled by gamers?”

I get the same shudders I get from utopian futures featuring the World Council of Scientists…

Seeing stories everywhere is pretty nice perspective. It is not, I’d say, the only useful perspective, but I don’t think anything is. (In other words: Seeing stories everywhere is not the final story to tell.)

Now, I’ll continue the digression on mathematics and stories.

Mathematics is all about stories. Take some simple concept, like the limit of a sequence (in some Banach space, say).

One story: You let the index grow and see what the terms approach.

Another story: You can select whichever epsilon and I can always find an index such that all the terms after that are at distance of less than epsilon from the limit.

Learning mathematics is learning a number of stories and using whichever is the most suitable at any given time, which is pretty similar to learning anything else. Whether something is true or not is a formal matter, but whether a given proof is a good one or not is a matter of telling good mathematical stories.

Nassim Taleb in The Black Swan talks about how human beings tell ourselves and others stories to explain how the world works. He uses the term “narrative” most of the time but that is what it comes down to.

What is particularly interesting about the concept is he is basing his concepts on a number of experiments that he developed and tested with a psychologist. Their research suggested precisely what you are saying, the best story wins, even when that story may be factually false or misleading.

Rob, sometime you and I should have a discussion on the oil spill. My perspective from working in the Canadian side of the oil industry gives me a neat vantage to look at the American goings on. I’m sure your training as an analyst will make for an interesting discussion.

Your point reminds me of a documentary I watched a few months ago called the Great Human Journey. One part I found especially interesting story about how early Homo Sapiens upon entering Europe came into direct competition with Neanderthals. There was some speculation about how and why we prevailed over the stronger, larger competitor and survived while they didn’t.

The common wisdom was that humans were creating better tools and thus the mechanics of such gave us the advantage. However archeological evidence proves this isn’t so. When comparing human tools to Neanderthal tools, the Neanderthal’s were superior in every measurable way.

So what did we have that they didn’t that allowed us to win out in the evolutionary war?

The noticable difference is that we were creating art. But not just that – the artistic representations Homo Sapiens were creating were found at different sites many miles apart. This indicated communication and sharing information across multiple tribes. Neanderthal Man has shown no indication that they were doing anything similar.

My point here is usually one to validate the arts as a pivotal part of of our evolution and survival… I’ve also thrown in religious significance from time to time, but in this case I believe it supports your perspective on this.