It is impossible to overstate how much modern game design rests on ripping off John Harper, Clinton Dreisbach and Jared Sorensen

The most basic resolution is binary: Success/Failure.

Ok, that may be a lie. The most basic resolution is NULL/Success, which is to say either it succeeds or it never happens in the first place. Consider how conflicts are “resolved” in chess – it just happens. The only way for it not to happen is for the move to not be made. For the moment though, let’s start with the binary.

Now, we play games of the imagination, so binary outcomes are a bit of a ham-fisted tool. There is a natural gravity towards some larger number of options, but also a limiter imposed by complexity. It is fairly trivial to generate an arbitrary number of outcomes (a d20 can have 20 outcomes, after all) but it is much harder for them to be genuinely meaningful.

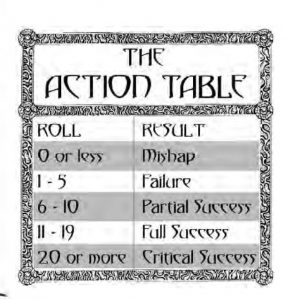

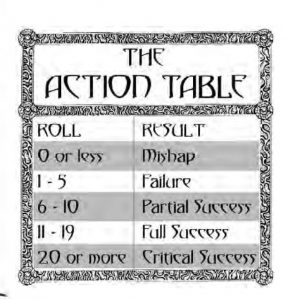

So game designs seek to thread that needle, and pick a path between those options. Or in some cases, outside of them. The first expansion on this was a 4 step model – Critical Failure, Failure, Success and Critical Success. This covers a decent range of options, but its assumption that critical are outliers makes it less flexible than it might otherwise be. That is, if critical happen enough to be part of regular usage, then they don’t feel like criticals.

The next step is to unpack that space between success and critical success, and the most common tool for that is some sort of margin of success system, where the amount that the effort succeeds by has a mechanical effect. This is nicely elegant – better rolls yield better results, which feels very intuitive. Unfortunately, it also tends to make scale a bit difficult to explain, since it often ends up a bit open ended (especially if the system has something like exploding dice). Saying 7 successes is what it takes to shoot a horsefly in a hurricane is great, but only if your system genuinely makes 7 successes that uncommon.

I note here that Green Robin’s AGE system struck a very nice balance here with a kind of light critical system where a better than average success gives currency to do cool things, but the effect is bounded.

The other possible approach is to expand the space between success and failure with a marginal or modified success. The idea is old, but I first encountered this in it’s explicit form in Talislantia 4e (coughJohnHarpercough) but nowadays it’s most easily recognized as the 7-9 result in Powered by the Apocalypse games. Of course, that can even be expanded to produce qualified successes and mitigated failures.

The thing is, we’re now up to a pretty wide spread of possible results on the dice:

- Critical Failure

- Failure

- Mitigated Failure

- Qualified Success

- Success

- Better success

- Critical Success

There’s a pretty obvious linguistic spread here

- Critical Failure (No, AND)

- Failure (No)

- Mitigated Failure (No, BUT)

- Qualified Success (Yes, BUT)

- Success (Yes)

- Better success (Yes, AND)

- Critical Success (WOO HOO!!!)

I’ll admit here, this would be more symmetrical without better success, or if I added a “worse failure” option, but I’m not sure how much fun there is in that. Critical failures can be fun as turns of dumb luck, and make for good stories, but worse-than-normal failures seem like they would be a punitive addition. On the flip side, having some space between success and critical success tends to allow a little more mechanical breathing room for cool tricks in system. As such, I’m ok with a little asymmetry.

But here comes the key question – the one I’m not 100% sure of the answer of. Is that too many outcomes? What is the right number of outcomes?

I don’t think there’s an answer for this, but I think there’s an interesting pointer to be found in thinking about it, because it reveals the question of how you’re going to use the outcomes.

That is, if you are providing these outcomes as guidelines for GM interpretation, then it’s probably close to the right number. It provides prompts that allow for most of the kinds of outcomes that make sense in fiction, so it’s just a matter of wrapping some guidelines around those tiers.

But if I was developing a more explicit system, one where the meaning of those outcomes all needed to be expressed as rules (think PBTA Moves), then this many result tiers could be cumbersome. I don’t want to have to write up that long a list for every single possible situation.

If I’m doing something in between – a system that MOSTLY resolves things one way, but has some explicit outcomes, then it gets a bit more subjective. For example, I might have a system that uses the same rules most of the time, but each skill has a different rule for critical success. In that case, it’s going to be much more of a judgement call.

So, there’s a perfectly reasonable case for fewer outcomes, but is there a case for more?

I admit, I used to think so. Ideally, I imagined outcomes as a subtle gradient between extremes, rich in nuance and interpretation. In practice, I have found that I simply do not have the creative juice to distinguish between every 7 and 8 on a d20 roll, and that I fall into roughly the distribution I outline above.

I’m not sure how useful any of this is, but it does reveal something to me about my tastes. See, that ladder of outcomes I like is VERY CLOSE to the ladder I internalized for diceless play from the Amber DRPG, which gave guidance in terms of running fights where the character was:

- Vastly Outclassed

- Outclassed

- Moderately Outclassed

- On Par

- Slightly Superior

- Superior

- Vastly Superior

And in my heart of hearts, I think that is what I’m striving for. For a host of reasons, not the least of which being how strongly it centers characters.

But where this gets interesting, for me, is that if this diceless distribution is what I’m really looking for, then what are dice really bringing to the table?

I have an answer, but at this point, that’s probably another post. 🙂

Ok, I have a new theory of crunch.

Ok, I have a new theory of crunch. As a result of my niece’s interest, I am now playing the first Danganronpa game. I admit, I had not been previously aware of this series (It’s a video game, and there have been several), and while I’m only a little bit in, I’m hooked. It’s sort of a character-driven-visual-story-puzzler-mystery full of anime tropes with a layer of weirdness. Which is to say, it’s very much to my taste.

As a result of my niece’s interest, I am now playing the first Danganronpa game. I admit, I had not been previously aware of this series (It’s a video game, and there have been several), and while I’m only a little bit in, I’m hooked. It’s sort of a character-driven-visual-story-puzzler-mystery full of anime tropes with a layer of weirdness. Which is to say, it’s very much to my taste.