This idea came to my while considering how to use 4e to run a Magic: the Gathering inspired game, and was refined some in discussion with Gamefiend. The problem, of course, is that 4e is not open enough to allow something like this, and there is prettymuch no likliehood of a M:tG RPG ever being something allowed within the bounds of any reality we know. But this is a fun idea, so it continues to rattle around my noggin with no hope of escape, so I’ve decided to finally sketch it down on paper (so to speak) just to get it out there, in part because soem recent discussion has touched upon elements of it.

At its core, this sticks to the basic form of 4e, though it would pretty much toss out the existing feat list in favor of something bigger – I’ll call them talents – which are effectively feat bundles. This, in turn, allows for the use of a single character class – let’s call it the adept – with great depth of customization.[1] Other changes would be within the existign scope – ritual magic would get fixed, skill list might get tweaked and, perhaps most importantly, the model of powers would get tweaked.

Specifically, the only “powers” would be the at will ones. Everything else is a spell.

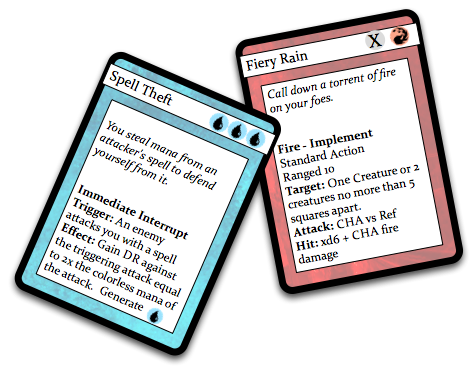

Now, spells woudl be structured in the same manner as existing powers (and, honestly, most of them woudl just _be_ existing powers) but with the enounter and daily elements removed, and replaced with a mana cost. This cost will look familiar to any magic player, as it will use that familiar icon language,

This is, I imagine, pretty self explanatory (provided you’re already familiar with 4e and M:tG). They’re used the same way as powers, but you have to spend the mana to make them go. So the question is where mana comes from.

In this case, that’s where at-will powers come in. By and large, they’re on par with basic attacks, but as an effect, they generate one mana of a specific color. Now, this means that there must be at least 5 potential at-will attacks, but will probably be more, just to cover other styles.

Characters start play as just a blank slate (stats + race) and the choice of a few talents[2]. Talents are the building blocks of characters, and there’s a whole discussion that can be had about what the non-M:tG talents woudl look like, but that’s another topic (and something of a genre decision). Suffice it to say talents do one of the following things:

- Mundane talents provide blocks of skills, proficiencies and maybe even normal (non-charging) at-will powers.

- Mana talents grant charging at-will powers (probably 2 per talent) and other abilities to increase or improve the characters “mana pool”[3]

- Spell talents give spells. Honestly, I’m not sure how many spells a given talent might provide, or how to group them yet. Striking the right balance between range of options and overwhelming the player takes experimenting. It might even require some sort of “hand size” limiter, so the hero can know any number of spells, but only use those in his “hand” at any given time.

And with that, you have the bulk of it. Grant new talents as characters advance, maybe tweak magic items a little so there’s a bit more emphasis on items able to carry a charge of a certain color or allowing mana manipulation rather than having expendible powers of their own.

Oh, right, ritual magic.

So, ditch the entire list, and the whole magic-item recycling element of it. Keep some of the effects in mind.

Next, add the capability to generate “non-combat” mana. I’m not really going to dwell ont his too much: it’s tied to talents, and it’s basically some amount of mana you can raise (but not keep) outside of combat, and possibly costs and means of exceeding that.

Next any ritual may have up to 3 effect: minor, lesser and greater. Not every ritual necessarily has all three effects, but most should. Those that don’t had best be kind of awesome.

The minor effect (the “cantrip”) of a ritual is the equivalent of a utility power, and is used the same way (and, in fact, will probably be written up as a power).

The lesser effect takes a few minutes (that is, a short rest) to complete, and has a more potent effect.

The greater effect takes hours (that is, a long rest) to complete and has an even more potent effect.

So, for example, the “Invisibility” ritual might break down as follows:

- Cantrip: Invisibility for a single round, or perhaps invisibility until you move or take an action. Something minor.

- Minor Ritual: Classic D&D invisibility – invisibility while you move and act, broken only when you attack or cast a spell.

- Major Ritual: Mass invisibility (or alternately, old ‘improved invisibility’).

In theory, there are “ultimate” rituals, with plot level effects, but their requirements are basically plot-device level, so there’s not a huge need to dwellon them now, except to note they make good player motives if they learn one (and preventing someone else from casting one can also be a fair motivator).

Talents basically affect how much and what mana you have access to, as well as how “big” a ritual you can learn. A novice ritualist might only know minor effects (aka “cantrips”), for example.[4] There are probably even tricks for speeding up rituals with preparation, but that’s a whole minigame of its own.[5]

Anyway.

I’ll probably end up using elements of these ideas in other games. Charging powers with attacks is super useful, and the ritual magic model is one that I admit I like a lot. In a less 4e model, I might get rid of spells entirely in favor of makign them all cantrips, but that would take some experimentation (and a bit less focus on diversity of combat effects).

As a final note, I obviously _could_ write this. It woudl not take much to shave the serial numbers off both components to make a non-copyright infringing game, but the reality is that I’m not sure that would be much fun. If I need to go through the effort of making it no-something else, it would probably be better to spend the effort making something new.

1 – In a perfect world, this game might be more modeled after the awesome Gamma World boxed set, in which case these modular components would be used to build a set of templates for speed of play. In this perfect world, this is properly productized and marketed, and also has rules for the mechanical use of actual M:tG cards (instead of GW’s custom decks) as well as creating a setting element to allow “between game” elements to be resolved with Magic duels.

2 – My gut says 3. 1 mundane, 1 color-generating, one spell set.

3 – For example, a talent might allow you to have a built in mana charge – say, 1 green. That 1 green recovers after a short rest, so it’s usually available at the beginnign of a fight. Simple enough, but I would totally demand a geomantic component – that mana comes from _somewhere_ – there’s a physical location (land) which the player has attuned to that the mana comes from, and if that land is lost or stolen, the hero needs to either recover it or find a new power source to attune to. Why yes, that is a built in plot goal.

4 – There’s a bit of ars magica here: greater rituals are not hobbled by dungeon balance. They’re a big deal, as they should be, and a more than fair tradeoff for not choosing combat-efficacy instead.

5 – In the published version, players probably have different Combat, Ritual and Greater Ritual mana “pools” (rather than lesser and greater rituals just requiring more mana) so that cards can continue to be used as direct mappings into the game. That is, if we want to have an in game of Armageddon (3W, destroy all lands) then we declare it a greater ritual, so that the player needs to accrue 3W in that pool, something their “combat mana” won’t help with. Shades of unknown armies!