Fred surprised me with the good news today! The previously mentioned It’s Not My Fault deck is now for sale on Drivethrucards! Whole thing will set you back nine bucks plus shipping (and maybe a box). If you’re like me and want to add things to your order to justify shipping, I definitely recommend getting some turn tracking cards or anything by Daniel Solis or Brooklyn Indie Games!

Fred surprised me with the good news today! The previously mentioned It’s Not My Fault deck is now for sale on Drivethrucards! Whole thing will set you back nine bucks plus shipping (and maybe a box). If you’re like me and want to add things to your order to justify shipping, I definitely recommend getting some turn tracking cards or anything by Daniel Solis or Brooklyn Indie Games!

Monthly Archives: November 2015

Respectful Failure

This is another one of those ideas that I make no claim to novelty of, but i want to talk about because it’s pretty important. Game design has been slowly getting its hands around the role of failure in play. It’s a big and complicated topic (that can look surprisingly simple) with many different answers, but a lot of good conclusions have been reached, at least intellectually.

This is another one of those ideas that I make no claim to novelty of, but i want to talk about because it’s pretty important. Game design has been slowly getting its hands around the role of failure in play. It’s a big and complicated topic (that can look surprisingly simple) with many different answers, but a lot of good conclusions have been reached, at least intellectually.

Now, first, it’s important to note that there is a mode of play where failure is supposed to be educational, presuming you survive it. It is a tool of exploration, and a necessary component of trial and error. If you miss a clue, then you might not solve the mystery, and the consequences will roll forth from that, so maybe you better hustle to find another solution. RPGs are pretty good at this type of failure, and it has its own body of technique which I’m not speaking to today, except to say that if this is what you’re looking to do, then totally don’t worry about the rest of it.

Another approach is based on the idea that failure should not stop play, and arguably should not stop fun. Failure, in whatever its form, should keep the game moving – failing forward, as it were. This idea is most clearly crystallized in Gumshoe, where investigation skills cannot fail, so long as there’s something to look for, because having a game come to a dead stop because of a failed roll is pretty dull. This same thinking can be applied to rolled failures – the character may still fail, but the plot will unfold in such a way that play will keep moving forward.

I am, I admit, a little skeptical of this approach. I heartily applaud the sentiment, and there are definitely situations where it’s applicable, but it shows some cracks in practice. It provides a lot of opportunity to showcase how many ways a GM can say “no” without actually saying “no” for one thing – judging applicability of the situation or requirements produce the same result as a no, but with a bit more absolution.

Also, practically, a lot of games with very generous theories of failure have very concrete mechanical measures of failure. Even if the game is going to be very generous about what failing a Socialize check might mean, odds are good the attack and defense rolls are pretty darn explicit in their outcomes.

This is not necessarily bad, but it’s worth being cognizant of.

The problem, I think, is one of mindfulness. GMs are busy, and when presented with a specific failure, they have incentive to take the simplest path through, and that is often either a flat no or a mechanical resolution. This is just human nature. But if you can get a GM to stop for a second and think “how can I make this result interesting?”, i think that almost every GM is capable of providing a satisfying answer.

That is to say, the problem is not one of creativity, it is a challenge of helping the GM stop and think. This is the real genius of the Powered by the Apocalypse (PBTA) 7–9 result – its specifics may be good or bad on a particular move, but it does not allow the GM to fall into a rut – she has to stop and think. And once you’ve gotten the GM to think, good things happen.[1]

Other rubrics can help. “Failure should move the plot along” can force the GM to think, but it’s a little bit plot-dependent. When it works, it can really keep things moving, but it definitely relies on a strong idea of what the plot is. I usually don’t, so that only helps so much.

My preferred approach is fairly predictable – as usual, I look at something plot centric and wonder about making it character centric. With that in mind, I practice something I call Respectful Failure. That is, the failure must respect the capability and concept of the character taking the action.

For example, if the character is a world class sniper, and they blow a roll to hit, then I cannot simply say they miss. That pretty much denies their concept. Instead, I must come up with an explanation for why they missed which is respectful of the character’s competency. That forces me to think, and it gets me a lot of what I love out of 7–9s in PBTA – it complicates the game. Why? Because when characters are very competent, their reasons for failure need to be interesting. To get back to our sniper, if he fails, then it might be because:

- The shot was lined up but that’s when the counternsiper opened fire

- Someone else shot the dude first

- It was a hit, but it was the body double!

- EXPLOSION!

And so on.

Note that my priority here is respecting the character, but the result of that is something that moves the action forward. This resembles advancing the plot, but it’s a subtly different beast, because I have no plot to speak of (also, it posits a very fluid gameworld, which is not to everyone’s tastes, and that’s fine – see the original disclaimer.)

Now, this is not necessarily something I will do on every roll, because not every roll is a showcase of the character’s concept. If our sniper tries to pick a lock, and the dice turn against him, I have no problem saying the lock is too well made and that he fails to open it (though I will not create a situation where picking that lock is the only way to keep playing, because I don’t hate my players) because picking a lock is something incidental to his concept. If he were playing a cat burglar, it would be a different matter.

Some games give very clear flags for which rolls deserve respect, and things like very high skill ranks and things like aspects are all useful pointers. But I admit there’s also a bit of reading the table and the situation involved – how much spotlight has that player gotten? How much do they want to have? What is the rest of the table interested in? Can the consequences of this toss the ball to someone else? The answers to questions like that help me adjust my decision making on the fly.

To go back to the lockpicking example, I might interpret a failure as picking the lock but triggering the alarm if the team’s hacker has been sitting on his hands for a while – the failure gives me a chance to toss the hacker the ball and give him a challenge to overcome.

And that’s a key technique there – a failed roll can easily be a success with consequences if you have a high trust table and loosely articulated stakes. If you’re doing strict stake-setting, this would probably be in bad faith. But strict stake setting is slow and boring, so that doesn’t worry me too much. 🙂

This works in most loose systems, but it has a particular challenge in Fate. We designed Fate pretty generously, enough so that failure is not terribly common, especially within the character’s core concept. As such, it is hard to get the cycle of respectful failure moving at the table with old habits. But I’m wondering if the right answer is to be a bit more of a bastard GM (I am usually too kind) and put more pressure on the fate point economy, enough so that the players feel more obliged to stomach the occasional failure. But that is a topic for future experimentation.

1- For the unfamiliar, a lot of rolls in Apocalypse World and other games using the engine work something like “Roll 2d6 plus a modifier. on a 6 or less, you fail. On a 10 or more you succeed. On a 7-9 you get a mixed result, like a success with complications or a failure with mitigation” with specific details varying.

Wrestling with FAE

Right before Metatopia, I finally got my hands around the element of Fate Accelerated that I kept stumbling over in the approached, and in retrospect, it’s super obvious. The problem, historically, is that it’s super easy to spam your best approach, especially with approaches like “clever” and that generally there’s a disconnect between how the various approaches feel in play. I’ve previously floated Fae 2 as a solution, and it still works, but I’m still digging into the underlying problem.

Right before Metatopia, I finally got my hands around the element of Fate Accelerated that I kept stumbling over in the approached, and in retrospect, it’s super obvious. The problem, historically, is that it’s super easy to spam your best approach, especially with approaches like “clever” and that generally there’s a disconnect between how the various approaches feel in play. I’ve previously floated Fae 2 as a solution, and it still works, but I’m still digging into the underlying problem.

For those who need to look it up, the approaches are Quick, Clever, Forceful, Flashy, Careful and Sneaky. In an ideal world, they act as adverbs, describing a character’s action, and coloring the outcome, and as such, it doesn’t matter much if a particular approach is used a lot – it just means that action will skew in that particular way, which is fine. The problem is that this only works if all of the approaches are equally applicable, limited only by player creativity.

But they aren’t, because some of these adverbs are also their own verbs, especially when you need to move quickly, sneak, or smash something. That is, certain approaches have implicit actions which are very difficult to decouple from the approach, and that’s a real problem when the character is trying to sneak carefully or quickly.

FAE2 offers one solution to this – let the player choose one approach and the GM pick the other, then add them up – and it works fine, but requires retuning difficulties a little. You could also modify FAE2 so the player simply picks both, and that works fine.

But what we’ve been trying a little is “Choose as many approaches as you want (practically caps at 3)” and roll the lowest. At first blush, this may feel punitive, but remember that FAE difficulties are skewed in such a way that even a +1 is pretty useful. And the tradeoff for the reduced bonus is much greater latitude in capable action – ut is very difficult to describe a character action, however convoluted, that can’t be thrown into the bucket of two or three approaches.

It also makes certain things pop. When a character can apply an unqualified +3, that feels like they’re getting spotlight. When a character is forced to roll a +0, it feels like that really is a shortcoming (without a lot of mechanical pain). It works pretty well.

Now, the counterargument is that we’ve largely been doing this with It’s Not My Fault and the random nature of character creation may make players more forgiving of this. Jury is still out, but we keep experimenting.

I also considered giving each Approach an implicit action, so that fine manipulation was always careful, and social manipulation was always flashy and so on. After some thought, it seemed clear that this was kind of backwards thinking, but it was useful for fleshing out my own thinking about what the Approaches mean. I don’t need a rule saying that flashy is manipulation, but having an understanding of flashy that says it encompasses influence, not just ostentatious display, makes it a little more clear to me when Flashy is appropriate. Clever? Does the action have multiple moving parts? That’s a good flag for clever. Careful? Consider that it encompasses patience and timing, and that’s a lot of action.

Practically, it’s important to get to the point where you can see why each Approach could be awesome. Without that, they seem lumpy and imbalanced, but with that understanding, then it becomes a firehose of action an excitement.

It’s Not My Fault!

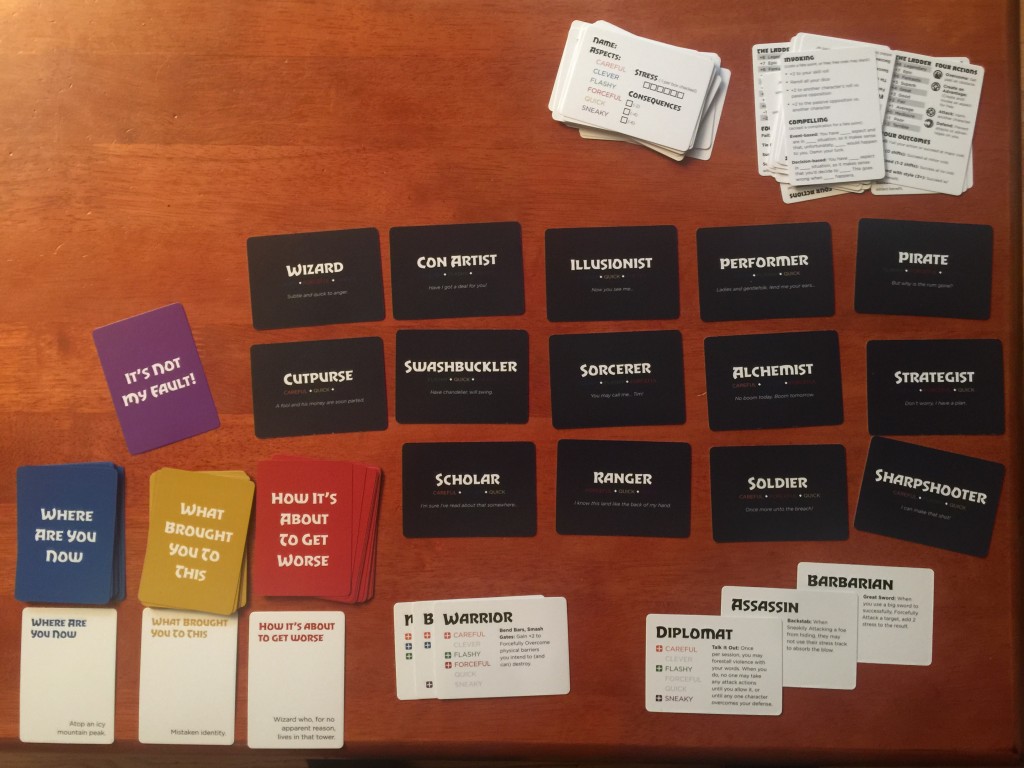

Fred and I ran something of a secret playtest at Metatopia. Yes, we had copies of the Dresden Files Cooperative Card Game to playtest, and that went swimmingly, but we had packed something else – It’s Not My Fault

There is a particular style of game that I’ve run a number of times for friend where chargen involved drawing cards containing archetypes. Fred took that idea and ran it through a filter of FAE, then combined it with Two Guys with Swords and added a great kickoff mechanism to produce a small deck of cards with which to make an on-the-fly RPG.

The model is very simple. There are 20 cards with archetypes like Barbarian, Swashbuckler or Illusionist on them. They have +1 to three FAE approaches, and a stunt on the back. Each players choose 2, and is dealt a third randomly. The result is a character with three aspects (like Alchemist, Merchant & Sharpshooter), a set of stats and 3 stunts.

The GM then draw from 3 piles: “Where are you” “How did you get here?” and “How’s it about to get worse?” Which might well be “In an arena before a chanting crowd”, “Lost a bet” and “The poison is already in your system”. With that framing, the GM points to a player and says, “Who is to blame?” and the player explains “It’s not my fault, because…” and blames another player. That player repeats the process, and repeats again, until the last player blames the first player. With each successive explanation, the GM is adding an aspect to the table, and the players are getting a sense of their dynamic.

And that’s it. You then start playing.

We ran chargen a few times, just to show the cards, but I also got toe run a session well past my bedtime on Saturday night, and it was just the kind of Lieber-esque madness it was supposed to be. Describing it cannot do it justice, but it should be known that a marriage was not consummated, the bar was burned down, and inthe words of the hanged man, “He’s a dick”.

There were one or two tweaks that still need t0 be made to the decks, but they’re mostly graphical stuff that Fred will fix in no time, plus maybe one or two tweakes , then we’ll probably put these up for sale, and consider future expansions of the line, if only for our own use. It’s not my fault…In Spaaaaace and such.

I also used this as an excuse to try another rule. Rather than giving out fate points, I grabbed 7 othello chips and tossed them onto the table. Any time players would gain a fate point or I would spend one, I flipped a black side to white. Any time the players spent one, I flipped a white to black. If they ever went all black, I would draw another “How’s it about to get worse?” card. If they ever went all white, the player’s once-per-session stunts would reset. It worked very well, though neither end was ever triggered. As expected, the tension was more rewarding than the actual threat. I’ll definitely try that again, though I may fiddle with the “all positive” reward, since it’s hard for the players to get that unless I really push.

The TVGame

So, I have an ur-RPG-system in my head that I have referenced occasionally and that I apply to almost every TV show I watch, which is composed of domains and ranks. Let’s call it TVGame for ease of reference, though really it works equally well for most fiction.

So, I have an ur-RPG-system in my head that I have referenced occasionally and that I apply to almost every TV show I watch, which is composed of domains and ranks. Let’s call it TVGame for ease of reference, though really it works equally well for most fiction.

Domains are areas of expertise, like fighting or computers. Every show has a different set of domains, since they reflect what the show is about. Something that might be a very broad domain in one show might be sliced finely in another. For example, Academics might be a fine domain in one show, but in something like The Librarians it might get broken out into Math, History, Biology or other fields (since most of the characters are academics of some stripe). Alternately, a lot of stories might offer finer gradations of fighting, to distinguish the sniper and the martial artist. Domains get very fiddly in the specific (and I could write several posts about them), but the idea is straightforward enough.

Ranks are a measure of how good the character is in the domain, broken down as follows:

Terrible – The character is not merely unskilled, they are actively terrible at this. Should they try to engage in this activity, it will almost certainly go horribly wrong in a manner suiting the tone of the show. Usually used for comic relief or to reflect full on barriers, like Professor X’s athletics.

Unskilled – The character has no particular training or aptitude in this field, but neither are they particularly bad. In most circumstances, they are unexceptional. A good example is driving – most people just drive without trouble, but are not actually trained drivers.

Capable – The character is good at this, usually good enough to be a professional. The majority of characters in any show are Capable at one or two things, and Unskilled at everthing else (Heroes and villains being the exceptions). Examples include cops, gangsters, teachers and really anyone.

Exceptional (or, as I say in conversation, Badass) – The character is super awesome at this particular thing. They’re the super hacker, the special forces assassin, the billionaire and so on. The protagonists (and villains) are probably exceptional at one or more things.

Transcendent – Like Exceptional, but more so. As with Terrible, this sees only limited use, since it usually exists for plot purposes, so there’s a place to put old masters and sentient AIs. Show that skew towards very wide competence porn may make use of this tier as a distinguisher, but that’s something to be careful about, because it can turn into an arms race.

The base mechanic is simple and diceless – higher rank wins. The bigger the margin, the more the higher tier dominates. If it’s more than one step, the higher ranked character does not just win, but effectively controls how the situation spools out. With this in mind, one of the “tactical” avenues of play is to leverage a situational rank boost. This is not easy, but it can be done to reflect things like overwhelming force. A mob of Capable cops can be a threat to an Exceptional soldier unless he can change the situation somehow. This is also incentive to try to move a conflict to a different domain.

If a conflict happens within a tier, that’s when you switch over to a more fiddly system. The actual fiddly system is kind of irrelevant, and can absolutely be tuned to your taste. It may seem kind of handwavey to describe it so briefly, but as with domains, the decision for how you handle conflicts is based on how you want your specific play to go. If you need it to be something, assume it’s Risus.

There are other bits. Adding aspects as a meta-wrapper is easy enough – in the main game, an invoke can increase your rank within limits. It can either let you bypass something with no particular opposition or can let you get up to a fair fight against opposition. Within the subgame for conflict, their utility depends on how the specific subgame works. Because of the granularity of this, it tends to work well for the “Few, but potent” model of aspects rather than the “language of narrative” approach, but I’m sure that can be tweaked.

Anyway, I want to share the TVGame because it gives me a decent way to talk about things I see on TV and how I’d game them up, which will be fodder for future posts.