Ok, nerdbusiness time.

There is a technique used in business called SWOT analysis, which is used for things like brainstorming or figuring out next steps. It’s a tool for stepping back and analyzing the reality of your business, group or the like, and hopefully gleaning insight into what to do next.

Conveniently, it is also a really handy template for adventure creation and for fleshing out your game. A PDF with the form and some directions can be downloaded here.

For purposes of illustration, I’m going to use Blades in the Dark, because the specifics of that game align particularly well with this approach, but the underlying idea applies equally well to any game where the players are a coherent group in a consistent context.

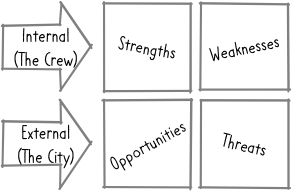

So, this technique, like so many expensive consultation driven models, is a glorified way to label four boxes. In this case, the boxes are summarized in the acronym SWOT:

S – Strengths

W – Weaknesses

O – Opportunities

T – Threats

The practice of filling in the boxes is largely self-explanatory, but there are a few tricks that can make it a little easier and more fruitful.

Strengths

What is it that the crew does well enough that someone else might want them to do it? That is to say, while crews can do a LOT of things, this is where we focus on things that might distinguish them from other groups, both generally and specifically.

Generally, the crew type is probably a pointer towards this, but it’s also somewhat incomplete. A gang of cutters might excel at doing violence, but that is something that many groups can do. What sort of violence does this crew excel at? Do you call them when you want maximum intimidation? Do they specialize in ambushes? Are they a top notch security force?

Individual character strengths also contribute to this, but only if it can be tied clearly to the team. If one of the team members is a master of disguise, that is only a strength if the group integrates that skill into its activities, rather than is just being an adjacent activity.

It’s worth noting that the real value of this list is often found in the combinations rather than the individual elements. That is to say, if strengths include “doing violence” and “knowledge of Six Towers”, neither of those are terribly distinguishing, but in combination they suggest an obvious opportunity the next time violence is needed that depends on the details of Six Towers.

Weaknesses

On the flipside, what is the group bad at? Where are they vulnerable? What kind of jobs do they really not want to end up needing to do.

As with strengths, the crew type probably provides some pointers towards this, but it will also probably be a bit less clear cut because there’s a good chance that the players have made choices to intentionally mitigate group weaknesses. For example, even in a group of slides and lurks, there is probably one cutter who acts as the team’s muscle.

The thing is, that does not cancel the weakness, it merely mitigates it. In our prior example, this crew would still be in trouble in a rumble, even if the cutter is able to put up some resistance, so their relative inability in a fight is probably still a weakness. But if a few more members toughen up, or if the gang recruits some muscle, then they might be able to offset the weakness.

In situations like this, look for the “single point of failure” – situations where the only thing which keeps a problem at bay is one individual or resource. If something happening to that individual would expose the crew to trouble, then that’s a weakness.

Weaknesses also may cover domains of operation or information. What happens if you drop this group into high society? The Docks? A roomful of ghosts?

Sidebar – In The Middle

The ghost thing raises a key point: there are lots of things which would be bad, but are not necessarily weaknesses. Just as crews can do many things which are not necessarily their strengths, there are many things which would be bad but are not necessarily weaknesses. The key thing to identify a weakness is that this group would be worse off in this situation than a comparable group. Similarly, a strength distinguishes the group in some way.

In short, most of the things a crew can do are neither strengths nor weaknesses, but are simply facts of life.

Context absolutely plays a role in this. To use one example, crew tier is not intrinsically a weakness or a strength – it’s just a fact of life. It becomes a weakness or strength in certain situations. If a small crew has big enemies, their Tier is weakness. if a large crew is throwing their weight around on a neighborhood level, their tier is probably a strength. But for a crew operating largely around its own weight class, it’s just the way things are.

Opportunities

Opportunities are things the crew could do but haven’t yet, for one reason or another. The reason might be as dull as “haven’t gotten around to it yet” or as challenging as “if only we could get past that dragon”.

Just as the crew type provides the first pointers for strengths, the crew sheet is the first place to look for opportunities. Right off the bat, claims are something of a laundry list of opportunities for the crew. Any adjacent claim is potentially an opportunity, with the main limiter being how well or poorly it’s been fleshed out.

Faction relationships also

Note that while opportunities can be very discrete (as in the case of claims) they can also be a little bit general (as may be the case with factions) in a “there is an opportunity there but we don’t know what it is yet.” An opportunity for an opportunity is still an opportunity.

One other useful thing to look at is the intersection between opportunities and strengths, and specifically ask whether the group has the opportunity to develop new strengths.

Threats

Where weaknesses helped us understand where the crew might be vulnerable, threats help us understand who might exploit those weaknesses or otherwise do harm to the crew.

It’s important to note that while enemies may be threats, not every threat is an enemy. While an enemy might consciously choose to exploit a weakness (if they know about it), there are other forces that will exert pressure on a weakness in an utterly indifferent manner. That is, if the crew is dependent on a single source for their goods, that’s a weakness. Even if none of their enemies know about this source, then that source is still vulnerable to other forces – his enemies, sure, but also the vagaries of day to day life. If your source is Iruvian and the Ministry starts rounding up Iruvians, that is a threat to the crew even though it’s not directed at the crew at all.

None of which is to say enemies shouldn’t be tracked here. Any faction with a negative relationship with the crew probably deserves a mention in this box. Even if they’re not actively engaging the crew at the moment, they certainly won’t pass up an opportunity if the situation arises.

Using the tool

Obviously, the act of using SWOT analysis is as simple as filling out the form, but there are better and worse ways to go about it. Critically, this benefits most strongly from being a shared exercise between players and GM, because getting EVERYONE’s answers to these question is incredibly informative, especially on the subject of opportunities and threats.

Opportunities in particular are an area where the GM really wants to know how the players see things, because if they players don’t see opportunities, then the game is likely to stall. Having an exercise like this where the group contribute their answer to these questions and express opinions on this is a much healthier way to flesh this out than to have the GM just present a buffet of things that she finds interesting.

Some GMs might feel a little bit of resistance to being equally transparent about threats for fear of spoiling surprises or telegraphing their next move to the players. This can be a fair concern, depending on the specifics of the table, but in that case the concern is easily mitigated by fact that there is no need to get to specific about how the threats might manifest. The table can have an open discussion about the fact that the crew’s hq is vulnerable without the GM needing to say “and this faction is going to exploit that”. If anything, getting buy in to the existence of the threat means players will be more strongly invested if it is brought to bear.

A Few More Tricks

- As the GM, if you are looking for ideas for your game, take a look at any group or faction connected to the crew (for good or ill) and do a SWOT analysis on them. I promise that after one or two of them

- Almost anything in the threat box can be a clock. Hell, feel free to put clocks IN the threat box.

- If it is not obvious what category something should fall into, use the following rule of thumb: Strengths and weaknesses are internal to the crew. They are things which are part of their nature, and (to at least some extent) under their control. Opportunities and threats are external to the crew, and are parts of the environment that the crew operates in, and are things to be responded to, but are not under the crews control.

I just tweeted about this, but I like this enough that i want to capture it here. I have finally gotten around to reading the new Over the Edge. It’s not released yet, but I backed the kickstarter, and the pretty-much-final preview version got sent around recently, and I finally sat down to read it. I had not read any of the previews before that for two reasons. First, OtE is an INCREDIBLY important game to me, so I was willing to be patient. Second, I hate reading multiple versions of a game because all the rules stick in my head, and I end up in a muddle when all is done. This is why I don’t read any of the preview editions of even games that I love and am super excited about, like all of the Blades in the Dark family of stuff.

I just tweeted about this, but I like this enough that i want to capture it here. I have finally gotten around to reading the new Over the Edge. It’s not released yet, but I backed the kickstarter, and the pretty-much-final preview version got sent around recently, and I finally sat down to read it. I had not read any of the previews before that for two reasons. First, OtE is an INCREDIBLY important game to me, so I was willing to be patient. Second, I hate reading multiple versions of a game because all the rules stick in my head, and I end up in a muddle when all is done. This is why I don’t read any of the preview editions of even games that I love and am super excited about, like all of the Blades in the Dark family of stuff.