Ok, let’s talk about Stress in Blades in the Dark.

This is an amazing mechanic – metamechanic even – that is easy to overlook. For all that it seems faily simple, it’s one of those things that really jumps out at you when you start looking at making hacks for Blades, and you find yourself wondering “Can I use stress to model THING?” and discover that the answer is “Yes. Yes you can.”

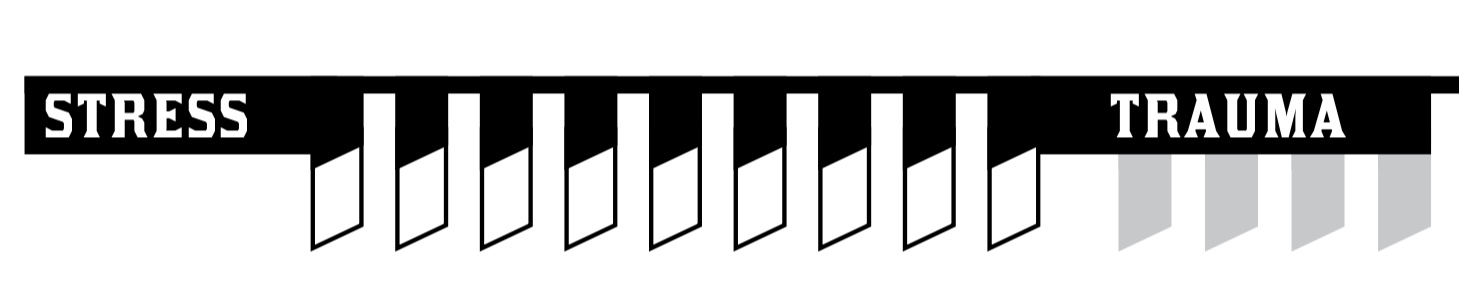

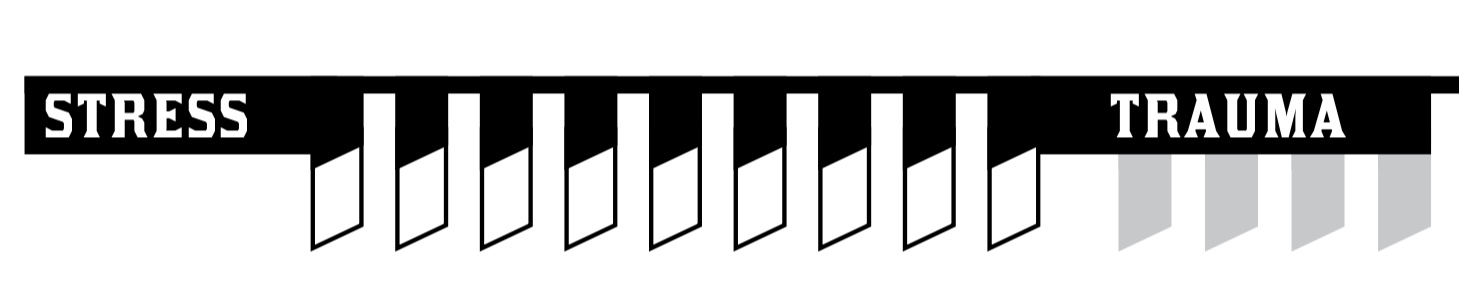

For the unfamiliar, BitD characters have a certain amount of stress, represented by a (mostly) fixed length track reminiscent of a Fate stress track, or the wound tracks from any number of games. Players can mark off stress for some effects like flashbacks or die bonuses (2 to push oneself for effect, 1 to assist an ally – very simple and nicely teamwork encouraging) but the real meat of the system comes up when it’s used for resistance rolls and how it’s recovered.

This is not going to come as a surprise to anyone who has played much Blades in the Dark, but it is not necessarily obvious when you read the rules or even if you just play it ones. Resistance rolls are one of the most powerful levers in the system – maybe the most powerful. They work as follows:

- Something bad happens to your character as a consequence of your actions.

- You do not want that thing to happen as presented, so you choose to resist.

- The thing does not happen. It may be cancelled, changed or mitigated.

- Dice are rolled and a cost of 0-5 stress is extracted. There are dire consequences if you don’t have enough stress.

Which is to say, guaranteed success, but unknown cost, though the cost is roughly predictable. It starts at 6, then you subtract the highest of 1-4+ dice from that. The player doesn’t know for sure what they’ll be rolling until the GM calls for it, but in a lot of circumstances you can guess, since the categories are largely Physical, Deception or Social, with weirdness only when it’s not in that space.

This is a wonderful mechanic on a few levels, so lets pull it apart.

First, this is possibly the purest expression of “Hit Points as Pacing Mechanism” that you could practically implement. The stress track defers consequences, so it extends the amount of time a character can stay on their feet and in play. But since it does not couch it as “damage” you don’t get the (now familiar) complaints that pop up if it were to actually frame social conflicts as “combat”.

Second, it has a degree of uncertainty, but also has the possibility of a “good” outcome. There is always the possibility of rolling a 6 on your resistance roll and paying no cost at all. If that was not there, then there would be a ratcheting inevitability that would suck away that potential thrill of victory.

Third, the level of risk is very knowable. When you look at your stress track and you know how many boxes you have left, you can make an educated guess at your odds. If you have 4 boxes left and are going to roll 3 dice? You’re probably going to be fine. But if you’re not? That feels fair. You are not getting blindsided by something being secretly harder than you expected.

Fourth, it introduces a mechanical point for the player to say “no”. This is kind of tangential enough to maybe merit it’s own post someday, but that invitation is a WONDERFUL addition to GM/Player interaction.

Fifth, it let’s the GM push HARD, because the players have the ability to pull it back. How well this works in practice has a lot to do with how much the GM respects resistance rolls, but it’s potentially very powerful.

Sixth and most relevant to this discussion, the use of stress for this purpose is a wonderful bit of sleight of hand because it frames stress in an agnostic manner. The terminology and presentation of stress is like it’s a real-in-the-gameworld thing even though it’s absolutely a meta-currency. The game would function just as well if the currency was “Darkness Points” or “Drama” or whatever, but not calling it that allows people to handle it like they do things like hit points – by just accepting it and moving on. Never underestimate the power of not picking a fight you don’t need to.

Seventh, it’s like saving throws that don’t suck.

So, resistance rolls alone would be a very robust use of currency, but there’s actually a whole engine here, which also includes how you regain the currency. Rather than resetting based on time or triggers, it is restored with explicit action (pursuing your vice) and even that has a little bit of risk (it is possible to overindulge). That risk is not huge, but it loads the choice to recover with some necessary thought when you have 5 stress to clear, and you’re worried about rolling a 6. (In case it’s not obvious, this is a wonderful solution to the 5 minute dungeon problem, which is a shame because Blades doesn’t have that problem.)

So, this is all great for Blades, but why am i so excited about this in a general sense?

Because this engine is covered in knobs.

Consider that this cycle of stress use and recovery includes the following things:

- Spending stress to do ARBITRARY SET OF THINGS.

- Spending stress to Resist an ARBITRARY SET OF THINGS with SOME RISKS

- Recovering stress by doing an ARBITRARY SET OF THINGS with SOME RISKS

Almost every game with some sort of currency does the first bullet, but tend to be a bit light on the others. And that’s fine, because the real trick is that every place where I wrote ARBITRARY SET OF THINGS or SOME RISKS?

Those are the things your game is about.

Like, not in some deep metaphorical way, but in the very straightforward “these are the actions you will pursue and the consequences you will face”. And those things, in turn, determine what the currency is.

That may seem circular, but let me illustrate. Stress works well for Blades because it’s a kind of unpleasant setting. Things are under high stress, and the consequences of things going bad are bad for mind and body, but are largely internal to the characters. After all, the main consequence of stressing out is taking on some amount of trauma, a change to the internal landscape.

Consider the very small change where we called stress “luck” and changed almost nothing else. The game would still play about the same way – you could press your luck, and your luck might run out. In that game, I suspect the consequences of your luck running out would be external – loss of resources, harm to the setting and so on. What appears to just be a change in terminology and tone becomes as change in rules because there is an explicit place to do it.

This is why it is so easy to think of other things stress might be (Reputation! Resources! Divine Favor! Popularity! Mana!) and then very naturally fill in what that means by changing the variables (the “ARBITRARY SET OF THINGS”) rather than the formula.

Combine that with the track-style presentation (which makes the whole thing friendlier to a category of players AND makes the use of currency feel more explicit and constrained) and you have a really powerful tool that is not hard to point in new directions. And, hell, while the specific details are tied to the BITD dice system? The model could be extracted further into any system you like. Hell, I could do it with D&D. I couldn’t sell it, but I could totally do it.

I just tweeted about this, but I like this enough that i want to capture it here. I have finally gotten around to reading the new Over the Edge. It’s not released yet, but I backed the kickstarter, and the pretty-much-final preview version got sent around recently, and I finally sat down to read it. I had not read any of the previews before that for two reasons. First, OtE is an INCREDIBLY important game to me, so I was willing to be patient. Second, I hate reading multiple versions of a game because all the rules stick in my head, and I end up in a muddle when all is done. This is why I don’t read any of the preview editions of even games that I love and am super excited about, like all of the Blades in the Dark family of stuff.

I just tweeted about this, but I like this enough that i want to capture it here. I have finally gotten around to reading the new Over the Edge. It’s not released yet, but I backed the kickstarter, and the pretty-much-final preview version got sent around recently, and I finally sat down to read it. I had not read any of the previews before that for two reasons. First, OtE is an INCREDIBLY important game to me, so I was willing to be patient. Second, I hate reading multiple versions of a game because all the rules stick in my head, and I end up in a muddle when all is done. This is why I don’t read any of the preview editions of even games that I love and am super excited about, like all of the Blades in the Dark family of stuff. This is a pretty good model. Good enough that I want to fiddle with it, but that’s another post. But there is one element of it I did not like at all, and that is the physical presentation of it, and it illuminated something about clocks to me.

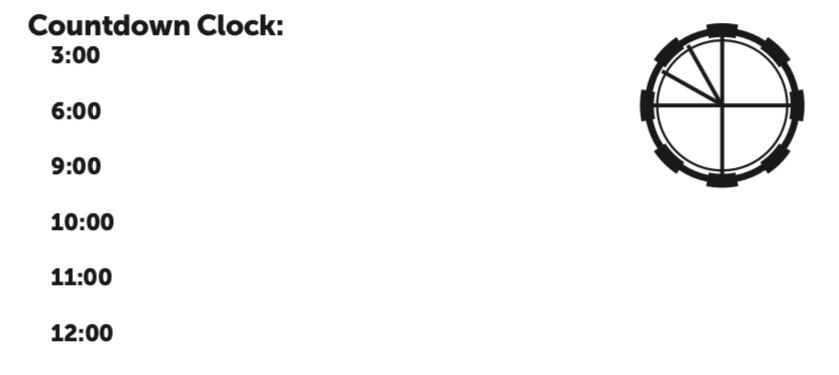

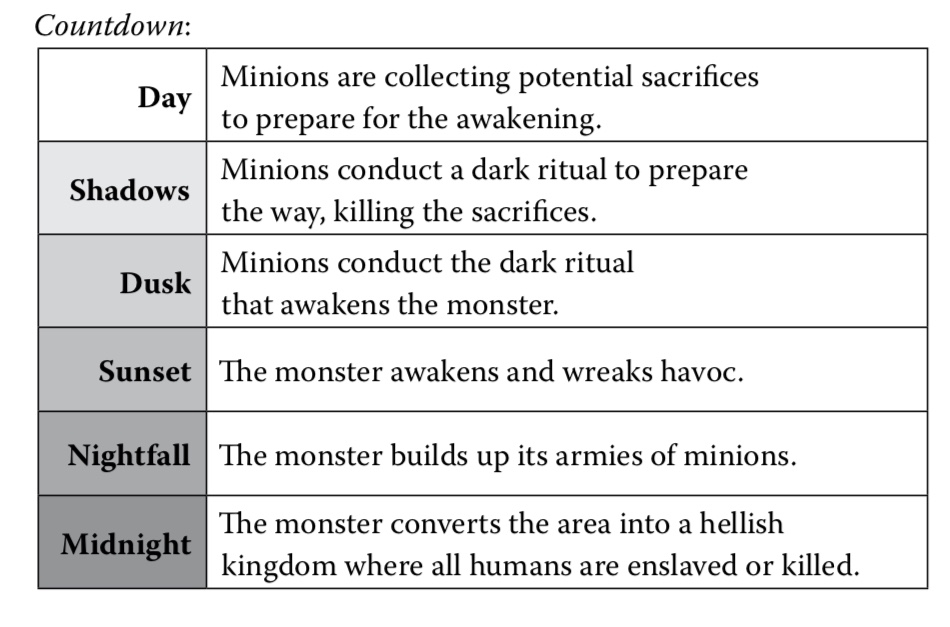

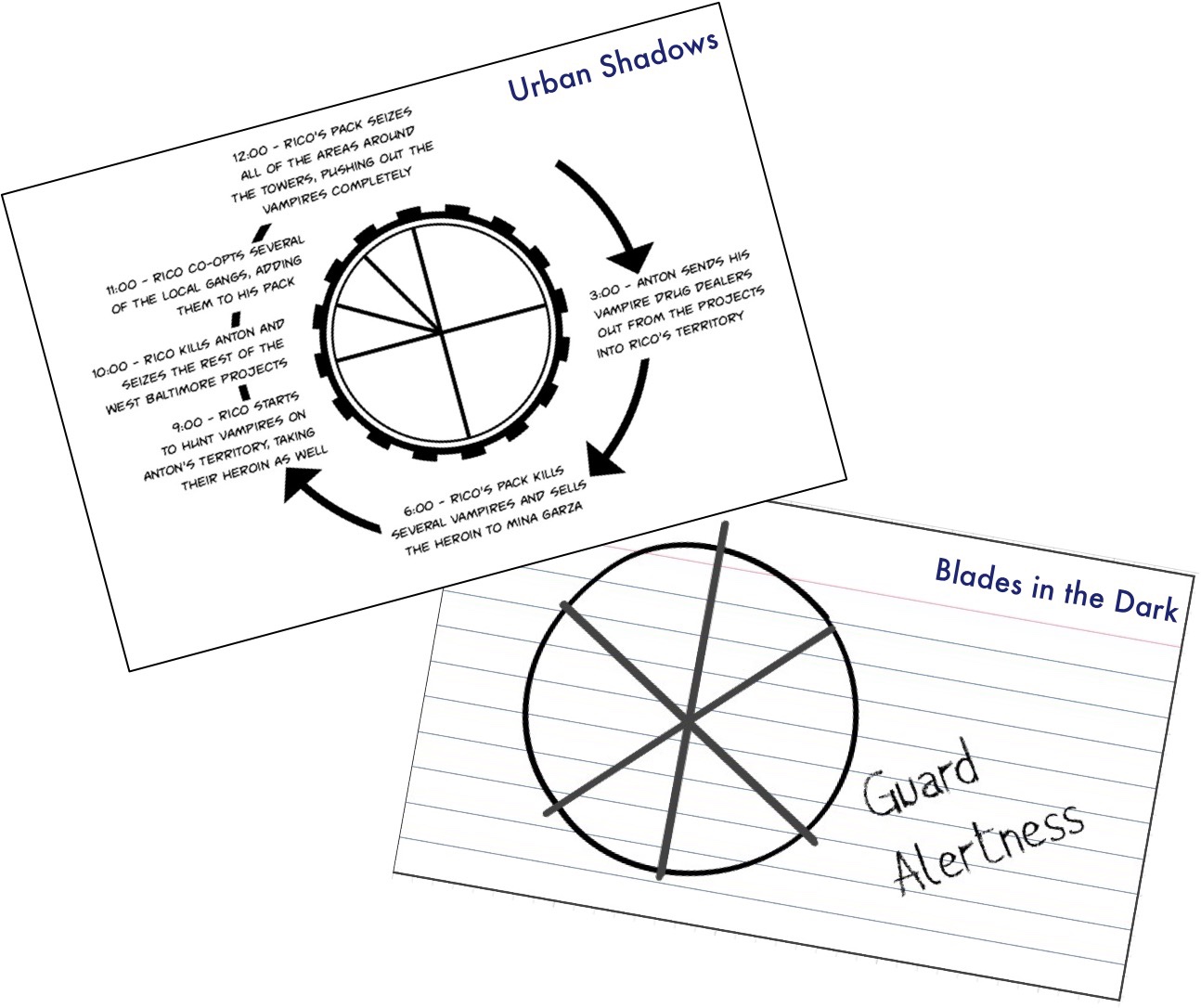

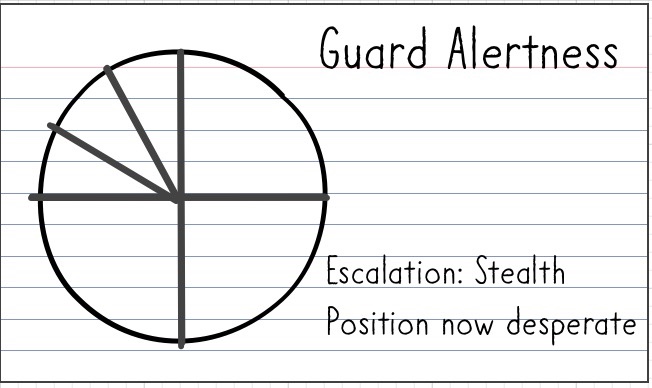

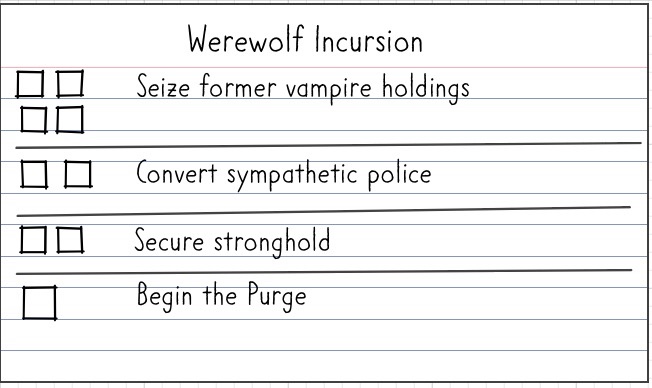

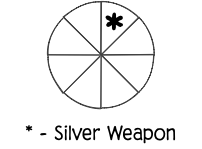

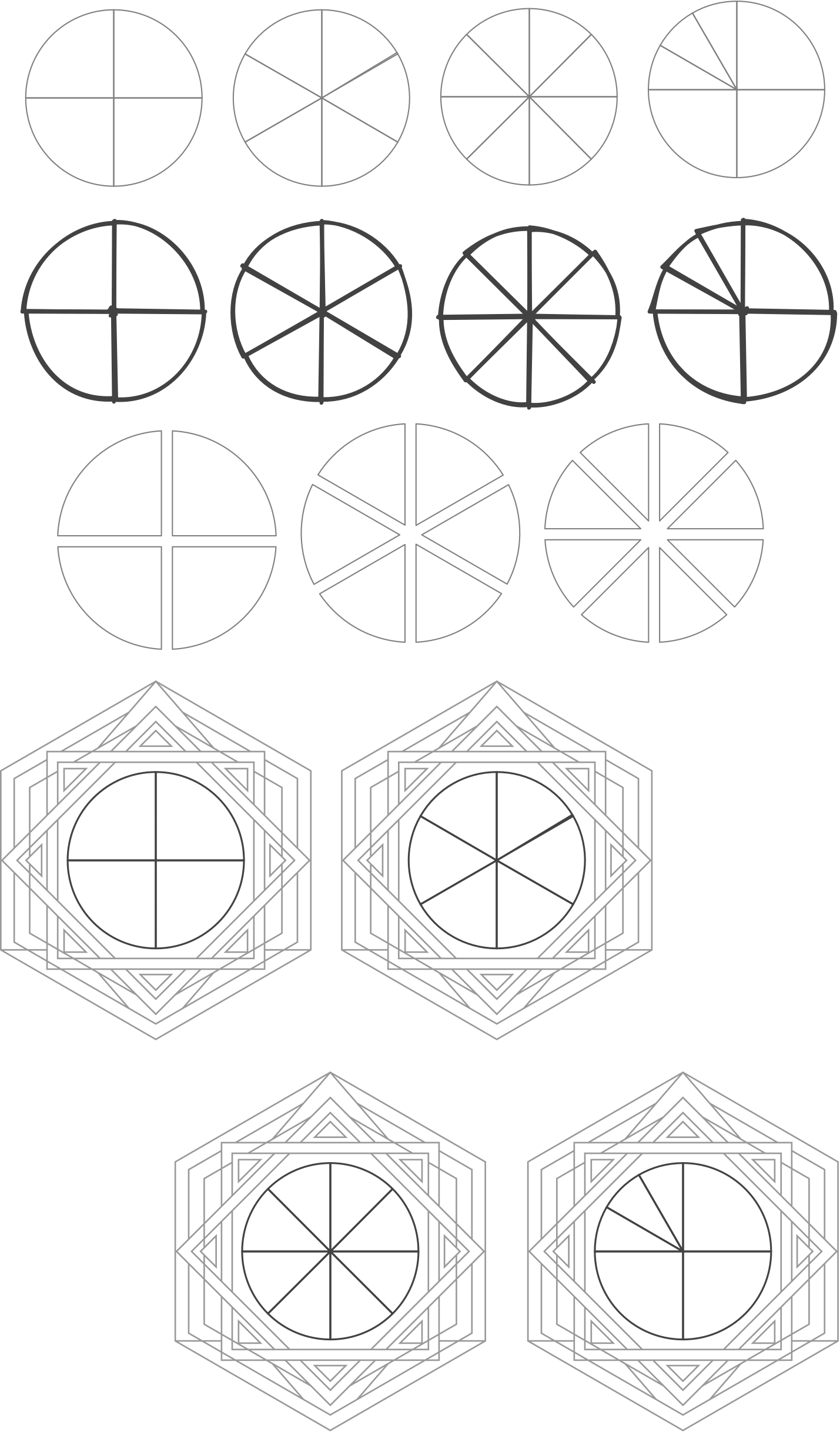

This is a pretty good model. Good enough that I want to fiddle with it, but that’s another post. But there is one element of it I did not like at all, and that is the physical presentation of it, and it illuminated something about clocks to me.