Ok, one ground rule on this. If I hit upon a topic that I already covered in the review of the Starter Set or the Basic Rules then I’ll probably gloss over it. No one needs me waxing rhapsodic on the virtues of Advantage/Disadvantage again.

Introduction

Short and sweet, with a lovely preface from Mike Mearls, this hist on most of the core ideas of the game, both mechanically (Dice, Adv/Dis, rounding) and conceptually (the describe environment -> describe action -> narrate result cycle, and the 3 pillars: Exploration, Social Interaction and Combat). There are also passing comments which make it clear that every D&D setting you can think of is in scope, which is nice.

There’s a bit on specific rules beating general ones, which is no shock, but no mention of a general rule for handling bonus stacking. This is an interesting omission, because previous editions needed to have very specific baseline rules to handle stacking abuses. From what I’ve seen, the reason for this omission is that a lot of what previously would have been abusable bonuses is now handled gracefully under the advantage/disadvantage system (which allows no stacking), and that the rest of the cases are largely set up so that stacking won’t be relevant. Still, it’s the sort of thing that leaves me looking for edge cases and qualifiers.

Starting Character Creation

Ok, first off, that art: the painting is lovely, but is that dude a ghost? He’s paying for drinks, so I guess not, but if he’s just an elf, he is an elf of strangely uniform color.

This sets up the procedural basics – Race, then class, then stats, then FABB (Alignment, flaw, bonds & background), then equipment. Core concepts like level, hit dice and hit points are explained, as well as the various methods of stat generation.

There’s nothing wrong with those rules, but there’s a bit of a procedural anomaly here – there are detailed chapters on the other steps (race, class, FABB and equipment) but none for stats. Instead, stat generation is presented in this introductory chapter, which means the procedure as read may seem more like stats, then race, then class, then FABB, then gear. I don’t think this is likely to create any confusion in an experienced player but it’s a little bit weird if you’re going through the book and building your character based on where you find the rules. Of course, the stats rules are short enough that it would probably have been hard to given them their own chapter, so I suspect this is an organizational issue of necessity.

It’s also nice to see the sample character getting made throughout these steps, though the one time I looked to those examples for mechanical clarity (for the money rules) I did not find it.

There is an explicit call out to the tiers of play (1–4, 5–10, 11–16 and 17–20) but, interestingly, those tiers don’t actually get named. As presented, they are general yardsticks for adventure scope (local, kingdom, empire,world) but that’s a bit fuzzy.

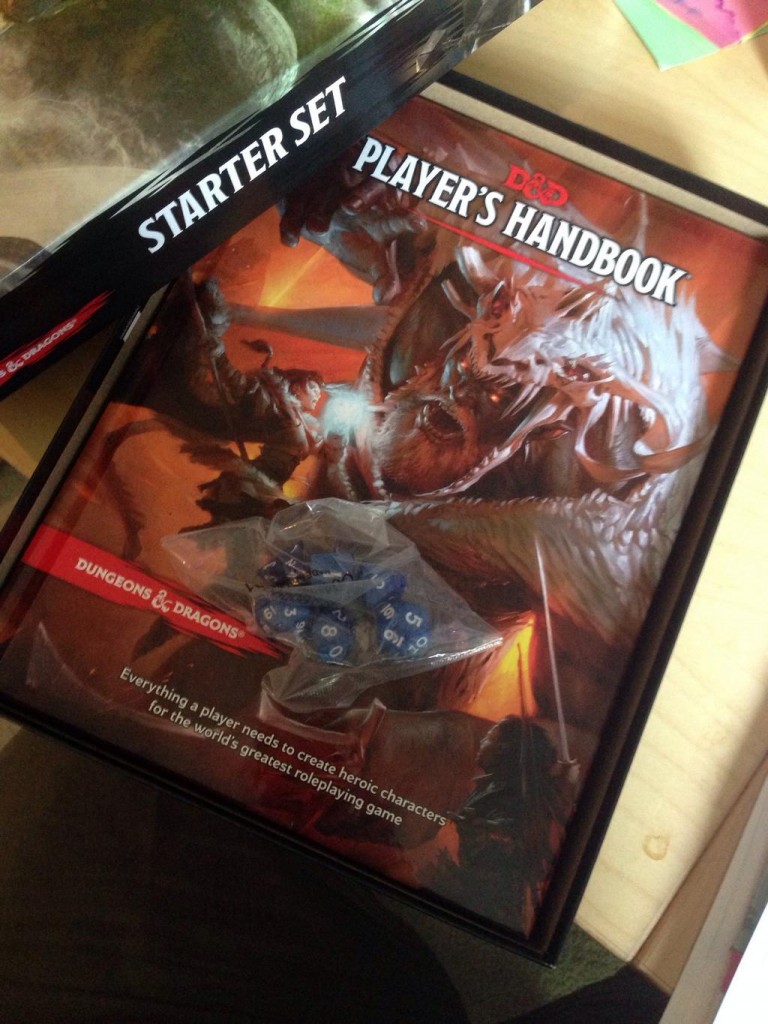

I actually assumed that these would be the general “bands” for adventures, in the style of the old AD&D modules (so 5–10 is maybe the new 7–9), but the Hoard of the Dragon Queen adventure is for characters levels 1–7, so that kind of blows that theory out of the water.

I should note, here, that I liked the concept of tiers in 4e very much, even if they mostly mattered at points where the rest of the game got too cumbersome for me. it feels like they expanded this idea in 5e by adding another step at the bottom. That suggests that a level 1 4e characters feels about like a level 5 5e character, and while that’s not precisely true, it’s not completely off base either. 4e characters just started more badass. And as such, this was probably a good structural choice. But in the absence of names suggests that this may end up being a bit vestigial.

Races

Pretty basic stuff structurally – stat mods, size, move etc. It’s called out that most races have subraces, which we’d already seen, but is still noteworthy.

We start with dwarves, and I love the iconic art. She reminds me of Violet from Rat Queens, so that’s a great reference. Also, it implicitly communicates that dwarven women (and perhaps dwarves as a whole, thank you Varric) need not be bearded, though nothing says they can’t be. There’s just a little bit of color to them (they have clans! and hate boats!) but the description does a nice job of framing dwarven longevity as important, something which is often overshadowed when compared to elves.

Mechanically, we’ve got the Hill Dwarves and Mountain Dwarves from the basic rules. They’re still pretty badass. Mention is made of the Dueregar, but (unlike the drow) they don’t get their own entry.

Folks who know me will realized I utterly cringed when I hit the elf section, as who is the iconic? Frickin Drizzt. And in case you weren’t sure, they actually put his name on the picture, something they do for none of the other character images.

The color is ok, and the wood and high elves are presented as expected, but we also now have rules for drow. And I should add, setting aside my unfondness for Drizzt, this is the first time I’ve been mechanically ok with the drow as presented, partly because this is the first edition of D&D where the sunlight sensitivity has more teeth than two weapon fighting has awesome. Specifically, they call out that the penalty (disadvantage to attacks and perception) applies if the drow or the target is in sunlight, so a deep hood won’t save you.

The popularity of Drizzt also reveals another unpleasant side to it, in the writeup of drow culture. It is so important to the character that he be a rebel that it basically means that there’s no chance for any consideration of adding more nuance to Drow culture than “eeeeeevil”. Of course, the idea that they’d reconsider that without Drizzt is probably purest optimism, so I probably can’t blame him for that. Much.

On to halflings. There has been some sort of decision in the art direction that halflings should have giant heads and spindly legs, and the net result looks a little bit creepy to me. Beyond that, though, they’re basically what we’ve seen.

The iconic human art is pretty badass, and they have actually found an interesting hook in the human color. There’s familiar stuff about ambition (because of short lifespans) but the hook I liked is that the distinctive thing about humans is that they build institutions. That is an interesting and thought provoking hook which makes a lot of pieces of generic fantasyland fall into place. It’s a little weird in the law/chaos sense, but I suspect that can be worked out.

Mechanically, the “Variant Human” rule is kind of neat – instead of +1 to all stats, you can get +1 to 2 stats, one additional skill proficiency and a feat. I have to admit, that’s a pretty amazing deal, and I’d be hard pressed to not take it if I, as a player, got to make those choices. Maybe too good a deal. It strikes me that it’s a great template for cultures in a setting, where each culture gets a different set of selections. That would make it a less overwhelmingly awesome tradeoff. And, hell, I wager that’s how it was intended originally, but cut for space reasons.

After these core races come the “uncommon races”: dragonborn, gnome, half-elf, half-orc and tiefling. This is interesting because these weren’t in the basic rules, so I’m curious to see the implementation. It’s also curious to see the implicit priorities that resulted in this list. A number of classic races (gnome, half-breeds) which got pushed out of the core 4e PHB are now back in prominence, along with the two races (tieflings & dragonborn) that had taken their slots. It’s a solid list, and probably covers the best range of races that people will start out interested in. Sure, there will be a few goliath or deva holdouts, but you can be sure they’ll be served in future products.

Anyway, we open with dragonborn, who have a lot of what made them fun in 4e: bonuses to strength and charisma paired with a breath weapon (and damage resistance appropriate to that breath weapon). They seem fun, but the most interesting bit about them is a piece of Dragonlance lore tucked into a sidebar, where they basically say that Draconians are Dragonborn with different magic in lieu of their breath weapon. That’s a significant retcon, but I admit it’s one that feels like it makes a lot of sense to me.

Next came gnomes, and they are always an interesting question, because they’ve never really settled in a niche. Are they more like dwarves, elves or halflings? Are they fae tricksters or crazed tinkerers? There are very strong examples in each direction.

5e solves this contradiction by offering two different gnome subraces. They share the bonus to int and certain saves, but after that, they’re radically different. Forest Gnomes are the fey tricksters, with a bonus to dex, illusion spells and the ability to talk to small animals. Rock Gnomes are artificers, with a con bonus, a proficiency bonus to tinkering and the ability to make small gadgets. I think this may be the biggest difference between two subraces in the game, but it’s probably the most elegant way they could have resolved the issue. So, thumbs up.

As with the dwarves, there’s a mention of deep gnomes, but no actual stats.

The half elf art is a little disappointingly bland, especially since the fiction is about Tanis. It woudl have been nice to see the half elf with a beard. That said, the color goes out of its way to emphasize that half elves are rare and mysterious, which is a nicely tolkein-y way to approach it THe mechanical elements feel a bit right, with some of the human generic flexibility (in stat and skill bumps) and eleven magic (darkvision, resistance to charm, immunity to sleep).

The half orc art is a lot more striking, but it’s very…pink. I think it’s supposed to be greyish (or so the description says)and it’s nice to have non-green orcs, but that particular grey just looks violet. Color wise, they very explicitly tie half orcs to marriages in an attempt to address the most problematic issue surrounding the race. Making lemonade, I suppose.

Mechanically, though? Holy crap. Bonuses to Strength and Con, darkvision, intimidation for free, roll an extra damage die on criticals and, once per long rest, when an attack would drop you to 0hp, drop to 1hp instead. Does that sound terrifying to you? Because that sure sounds terrifying to me.

Not sure why, but the tieflings are purple too. Now, I’m a fan of the old DiTerlizzi tieflings, back when they had no unified appearance and rather all carried some distinctive mark of their infernal heritage. I was not terribly excited when 4e made them a unified race, but I had to acknowledge that the art looked awesome, and the rich red color was really striking. As described, they’re still red, but the example art really undercuts a lot of the goodwill that 4e had earned.

Mechanically, bonuses to intelligence and charisma, darkvision, fire resistance and some intrinsic spellcasting. All fun enough.

All in all, it’s an interesting chapter. Race is definitely designed to carry a lot of mechanical weight, maybe moreso than any other edition. Every race feels like it has a compelling mechanical argument for why its cool, and that’s pretty hot.

Also, it’s very clear where the hooks go in for expansion material. Setting aside the addition of new races (which is a certainty) the ability to add new subraces and build mechanics that hang off the existing races is quite obvious. It is easy to envision a Complete Book of Smallfolk with extra subraces for Dwarves, Halflings and Gnomes (including the deep races) as well as other mechanical hooks (feats, class abilities) that are tied into race. You could fill a slim hardcover with that quite trivially.

Which is where the spectre of the license raises its head. These products will exists – the question is whether WOTC will be taking steps to keep them in house, or if they’re going to open it up to third parties.

Classes

To answer the most important question: barbarian, bard, cleric, druid, fighter, monk, paladin, ranger, rogue, sorcerer, warlock and wizard. As with the race list, there’s some interesting implicit information with the list. As with the races, the popular favorites that 4e had shuffled off into supplement-land (the barbarian, monk, bard, druid and sorcerer) are back, front and center (at least in part because each class now takes up less page count). 4e’s warlock has returned, but the warlord has not. There is also no sign of psionics, which is probably just as well for the core book.

The barbarian’s place in alphabetical order has historically been a little bit awkward, since it’s not always a great class to showcase the system. 13th Age solved this problem by making it the simplest class, and 5e takes a similar, but not identical, track. There are still fiddly bits, but the Barbarian is really well designed as “the smasher”, which is probably about right.

The “no armor” thing is handled by Barbarian AC being equal to 10 + Dex + Con (+ shield) when unarmored, which is pretty badass. That’s not too unexpected, but the real question was, of course, “how do they handle Rage?”. The answer: pretty damn well.

Basically while raging, you get a bonus to strength checks, (not attacks, at least as I read it), damage and you have resistance to most weapon damage. Rage lasts a minute, and you can do it a few times a day. Notably, there is no downside to raging – it’s just a bit of extra badass. If you take the Primal Path that focuses on rage, then it becomes even more potent but you are exhausted afterwards. Or you can just take the Totem Warrior path and never worry about it. More on that in a minute.

Most of the abilities are just more badass. Extra crit damage (hello half-orcs), more rage, faster movement and so on. That said, there are a few interesting mechanical bits. Reckless Attack" captures all the fiddliness of previous power attack rules in a nice, elegant resolution. Gain advantage on an attack this turn, everyone else gets advantage to attack you this turn. Clean and simple. Indomitable Might* is just clever – if your total for a strength check is less than your strength score, use the strength score instead. Slick way to set a floor on outcomes.

The totem warrior path is neat, but it feels a bit like “we need something that’s not just more rage…what have we got?” It lets you ritually speak with animals, but mostly it lets you choose a totem (bear, eagle or wolf) to gain extra abilities in and out of rage. That they are basically protection, fury and arms is not lost on me.

All in all, the class seems fun, and it gives us a heads up on what’s coming next. Specifically, a lot of the classes have two things in common. First, they have a choice. For the barbarian it’s primal path, for the Bard it’s Bardic College, for the Rogue its Roguish Archetype and so on. These are always called different things, but their general structure is the same – somewhere between levels 1 and 3, a choice is made in the character design which can differentiate it from other characters of the same class. For all intents and purposes, these are subclasses, and I will likely call them such.

The other commonality is a currency. Not every class has these, but most do – it’s a limited resource that recharges under certain conditions and can be used for a variety of things. The Barbarian has the simplest currency in the number of rages, which recharge after a long rest. Monks have Ki, spellcasters have spells (arguably its own thing), Bards have inspirations and spells, and so on. This currency management is something worth paying attention to when picking a class, and is also a reason that 5e is an absolute blessing for Campaign Coins.

Oh, ye gods, I think that’s enough for today. I’ll pick up again later with the Bard.