When I first started running Blades in the Dark, I was enamored by the ease of preparation. Very little player planning, dice driven action snowballs, just lots of great stuff.

But by the time I ran my third session, I was starting to notice something. As a GM, there was starting to be a bit of same-ness to the jobs, specifically the jobs of the same type.

That is, it was very easy to spontaneously improvise the first few stealthy infiltrations, but after a while it started to feel a little bit forced. There was a temptation to skip to the end, and a risk of “ok, now for ANOTHER sneak roll”, and I wanted to steer clear of that. Specifically, when I caught myself narrating a series of rooms, I felt like I had slipped a gear.

I’m sure there are other solutions, but for me it meant a bit more planning. Not a LOT more planning – I have no desire to slow down the game, nor to thrust canned encounters on my crew – but enough to force myself out of comfortable patterns and make me think about what makes this job different than other jobs.

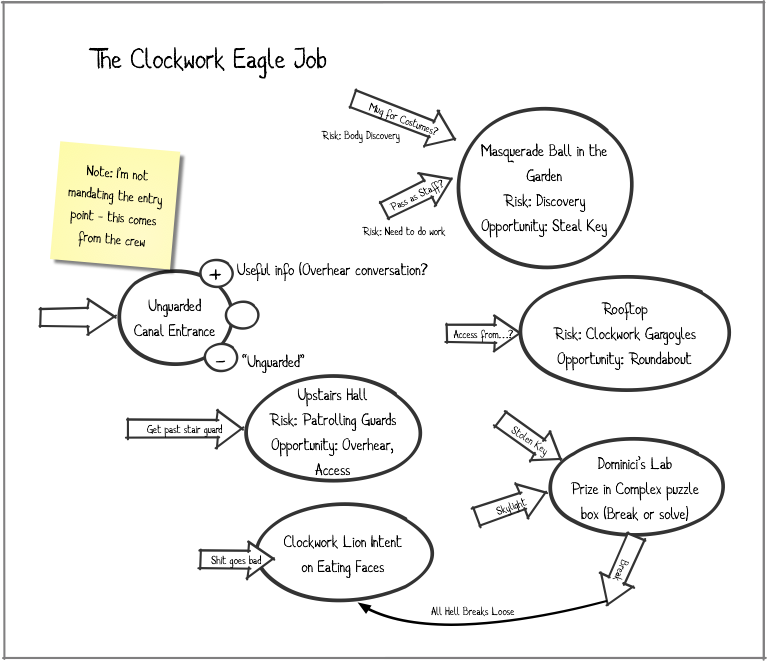

For this, I turn to my old friend, the node map.1 I start from the two points I have: The point of entry and the score. The players provide me the essentials of both of these, so I just need to layer on top of it. For the point of entry, I need to provide a little bit of context: What kind of place is being entered and what’s the outside like? I don’t need a lot of detail, but I need enough that I am ready for any result on the engagement roll. Practically, this means I need to think of something that can go poorly and something that can go well, as well as the middle of the road result2.

I also think about the payoff. If I were to just skip past all the infiltration and get to the point where they’re cracking the safe or getting the idol off the mantle, what does that scene look like. This is usually the easiest creative exercise, and it’s mostly a matter of coming up with a threat or challenge to drive the scene. I apply similar thinking to the engagement roll, only reversed – how does the framing differ if things are going poorly or very well? Will there be extra guards? Will the princess be in another castle? Will the macguffin be left lying in plain site since no one even suspects trouble?

So, now I’ve got two nodes, but I explicitly don’t connect them yet. Also, there’s an instinct to think that I am now looking at the beginning and end of a sequence, but resist that. It might be true, but I also might be looking at the beginning and middle of a sequence, or even just the first two steps.

So, rather than build a map, now is the time to think of a few more nodes. My target number is three, but you do you.

I don’t particularly restrict what nodes are. They might be rooms, they might be NPCs, they might be events or they might be something else. Practically, they just need to be something that could drive a scene, and the details flow from that need.

Coming up with nodes is a creative exercise, which runs the risk of bogging things down, so my process is to run through a quick checklist and see what it shakes loose. My personal checklist is:

- Is there a visual for a scene that I can see in my head that I want to capture?3

- Which crewmember is least well suited to this job? Can I engage them? What can I do to balance spotlight?

- Does anyone have outstanding trouble (NPCs in particular) that I could use bring in?

- Did the final payoff node suggest to me any logical barriers, gates or thresholds?

- What would play to the crew’s strength to reinforce their awesome?

- What would reveal the crew’s weakness and force them to scramble?

- What is going to happen if the shit hits the fan?

Running through that is usually enough for me to shake loose a trio or more ideas (though if I’m being honest, I often shoot for four ideas, since the “when the shit hits the fan” one is necessary in design but optional in play). I don’t want to throw too much detail at these things, but I like to note the risks and opportunities in each node, and that tends to give me enough to roll with (though it does run the risk of not having much “middle”).

So, I quickly add those three nodes to my notes. I still haven’t drawn any connections between them, but that is the next step. Ideally, I don’t need to connect any of them (more on that in a second), but if it seems like two of them should be connected by story logic (if, for example, the core needs to pass through the guardhouse to get to the treasure room) then this is when I connect them. Beyond those, I keep want to keep the connections loose, so that these elements can be brought to bear in alignment with the events of play4.

At this point I’m ready to go. I have a set of tableaux to be played through, and it’s just a matter of connecting them according to player actions. However, if I have a little more time, I like to add one more layer in the form of transitions.

So, if I actually drew this out as a map, I would be treating each connecting line as a transition, and I’d attach something to it (generally either some sort of choice or a bit of mechanical engagement, like a roll). Story wise, this translates into simple things that don’t merit a whole scene, like a locked door, a branching path, or a guard to be snuck past with no particular fanfare. Since I’m not mapping out connections, I don’t worry too much about choices (since they’ll shake out organically) but I do want to add a little bit of mechanical teeth to the transition between nodes – so how do I do that without explicit connections?5

The trick is that I add attachment points to the nodes, so that if I have an idea what entry (or sometimes exit) from a node should entail, and when it comes time to connect to that node, I connect to the attachment point and use that to inform the transition. It’s not perfect – sometimes circumstances will make the attachment points moot, but they’re lightweight enough (like, a bullet of fiction and a suggestion for outcomes) that it’s no great loss.

Finally, as I’m ready to go, I treat this diagram as a starting point, not a source of truth. As things come up in play or ideas come to me, I may add new nodes, change or update things, and generally keep it coherent and dynamic.6 But it means that with a single sheet of paper7 I have all the details needed to keep a job feeling fresh, with extra space for any clocks that may come up.

- While I am not strictly reframing jobs as 5 room dungeons, that’s not too far off from what I do. ↩︎

- This is not a super nuanced Way to run engagement rolls, but I am ok with it. ↩︎

- Confession: That usually means “Was there a cool bit in Dishonored or some other game that I want to copy?” ↩︎

- This is, I should cop, illusionist as hell. If you find that objectionable, then you should do all the connections now, and then run your crew through it. It’ll work fine. ↩︎

- Technique tip: Transitions that have rolls do one of two things. Either they force a choice (if you can get past this door, you go through to the nest node. If not, then you need to go to a different node to go around) or they function like mini-engagement rolls to frame the next node. They can do other things too, but the important thing is that the results of the roll are expressed in the subsequent node because it’s more interesting than the transition. If the transition is interesting enough to merit more than that, it should probably be a node.

Bonus Tip: This also 100% works for D&D. ↩︎ - Again, illusionist as hell. Feel free to plan this stuff out if you want. ↩︎

- Or, more often, an iPad. The ability to reposition things electronically is kind of awesome. ↩︎

This is a great framework, and as a brand-new Blades GM, I’m going to steal it. Thanks!

Excellent. What do you use on iPad for this type of node map?

Omnigraffle! (It’s what I do 90% of my graphics with)

Do you do this exercise at the table while running the session or is it for GM happy alone time? I don’t think I could get through all of this in the middle of a session personally, but when I ran Blades we were in complete improv-land and before a session I had no idea what job the crew might decide to do during the session. This may have been a mistake, as I also often struggled with keeping jobs diverse and interesting, especially in “how does it start” (based on the engagement roll) and “how many obstacles and what are they”. So I think the jobs I ran tended to be pretty terse, especially if folks rolled well.

Largely GM happy time. In practice it tends to be sloppier but pretty fast. Plus, once you do it a few times, you start building a mental library of nodes, which makes it even easier.

This is awesome! Many thanks, GMing Blades right now and have run into some of the same issues you have – this post has given me some great ideas, thankyou. We’ve been playing quite a while now and our games are quite heavy on the social / NPC interaction etc. and action tends to be seen as a hurdle to quickly ‘get through’ and back to the social interaction, which is fine of course each game group has a different dynamic but it’s nice to have a tool kit like yours to give more substance to the action. I’m wondering if the situation we’ve got is because our crew are hawkers? Guessing a band of assassins for example would have a very different dynamic!

I honestly think life is a little bit easier for bravos, assassins and shadows when it comes to job planning. The crew I play in are also hawkers, and it gets weird sometimes as our jobs often end up being things like “host a dog show” or “throw a party”. It’s great fun, but definitely feels like a slightly different game than the one deacribed.